The patient moved into a large assisted living facility in Raleigh, N.C., in 2003. She was younger than most residents, just 73, but her daughter thought it a safer option than remaining in her own home.

The woman had been falling so frequently that “she was ending up in the emergency room almost every month,” said Dr. Shohreh Taavoni, the internist who became her primary care physician.

“She didn’t know why she was falling. She didn’t feel dizzy — she’d just find herself on the floor.” At least in a facility, her daughter told Dr. Taavoni, people would be around to help.

As the falls continued, two more in her first three months in assisted living, administrators followed the policy most such communities use: The staff called an ambulance to take the resident to the emergency room.

There, “they would do a CT scan and some blood work,” Dr. Taavoni said. “Everything was O.K., so they’d send her back.”

Such ping-ponging occurs commonly in the nation’s nearly 30,000 assisted living facilities, a catchall category that includes everything from small family-operated homes to campuses owned by national chains.

It’s an expensive, disruptive response to problems that often could be handled in the building, if health care professionals were more available to assess residents and provide treatment when needed.

But most assisted living facilities have no doctors on site or on call; only about half have nurses on staff or on call. Thus, many symptoms trigger a trip to an outside doctor or, in too many cases, an ambulance ride, perhaps followed by a hospital stay.

Twenty years after the initial boom in assisted living — which now houses more than 800,000 people — that approach may be shifting.

Early on, assisted living companies planned to serve fairly healthy retirees, offering meals, social activities and freedom from home maintenance and housekeeping — the so-called hospitality model.

But from the start, the assisted living population was older and sicker than expected. Now, most residents are over age 85, according to government data. About two-thirds need help with bathing, half with dressing, 20 percent with eating.

Like most older Americans, they also generally contend with chronic illnesses and take long lists of prescription drugs — and more than 80 percent need help taking them correctly.

Moreover, “these places became the primary residential setting for people with dementia,” said Sheryl Zimmerman, an expert on assisted living at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

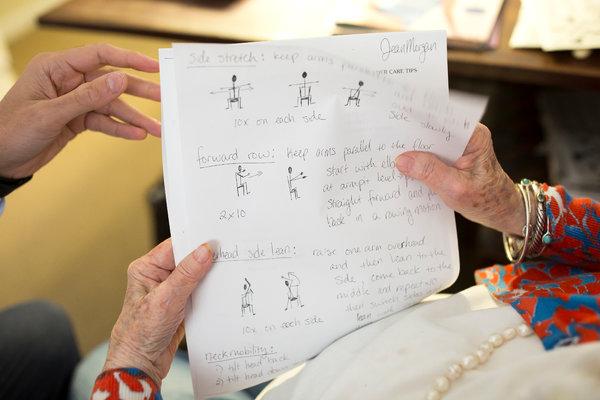

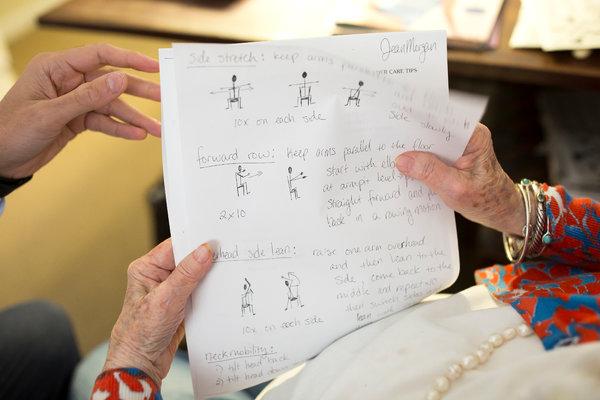

Dr. Bengali reviewed exercises for Ms. Morgan at the Brookdale facility.CreditMadeline Gray for The New York Times

About 70 percent of residents have some degree of cognitive impairment, her studies have found. So residents can find it difficult to coordinate medical appointments and tests, and to travel to offices and labs, even when facilities provide a van.

“The assisted living industry has to recognize that the model of residents going out to see their own doctors hasn’t worked for a long time,” said Christopher Laxton, executive director of AMDA, a society that represents health care professionals in nursing homes and assisted living.

His recent editorial in McKnight’s Senior Living, an industry publication, was pointedly headlined: “It’s time we integrate medical care into assisted living.” AMDA is considering developing model agreements.

“There has to be more attention to medical and mental health care in assisted living,” Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “Does everyone who falls really need to go to an emergency department?”

Lindsay Schwartz, an executive at the National Center for Assisted Living, a trade association, said in an email that “assisted living has certainly expanded its role in providing medical care over the years by adding nursing staff and partnering with other health care providers, among other ways.”

But persuading most operators to provide medical care likely won’t happen without a fight. They’ve built their marketing strategies on looking and feeling different from the dreaded nursing home, and they object to “medicalizing” their communities.

“They don’t want the liability,” said Dr. Alan Kronhaus, an internist who, with Dr. Taavoni (they are married), started a practice called Doctors Making Housecalls in 2002.

The facilities also “live in mortal fear of bringing down heavy-handed federal regulation,” he said. That can happen when Medicare and Medicaid, which cover most residents’ care, get involved.

Doctors Making Housecalls provides one example of how assisted living can offer medical care. The practice dispatches 120 clinicians — 60 doctors, plus nurse-practitioners, physician assistants and social workers — to about 400 assisted living facilities in North Carolina.

“We see patients often, at length and in detail, to keep them on an even keel,” Dr. Kronhaus said. By contracting with labs, imaging companies and pharmacies, the practice can provide most of the medical care for more than 8,000 residents, on site and around the clock.

Working with a local emergency medical service, he and his colleagues reported in a 2017 study that the practice could reduce emergency room transfers by two-thirds.

The Lott Assisted Living Residence in Manhattan, on the other hand, relies on a single geriatrician, Dr. Alec Pruchnicki, to provide medical care for most of its 127 or so residents.

If they’re feeling sick, a family member calls or the resident just knocks on the door of “Dr. P’s” basement office. “Sometimes it’s just a cold — chicken soup,” Dr. Pruchnicki said. “But this winter we had a few cases of flu and pneumonia, things you need to treat.”

Nearby Mount Sinai Hospital employs him and provides emergency services when needed. Often, they’re not. In 2005, Dr. Pruchnicki reported at medical conferences, he decreased hospitalizations by a third. “I can’t be in the only place in the country where this would work,” he said.

Spending time in emergency rooms and hospitals often takes a toll on residents, even if their ailments can be treated. They get exposed to infections and develop delirium; they lose strength from days spent in bed.

Perhaps that contributes to short stays in assisted living. Adult children often see these facilities as their parents’ final homes, but residents stay just 27 months on average, after which many move on to nursing homes.

Adding doctors to assisted living could also cause problems, advocates acknowledge; in particular, it might increase the already high fees facilities charge.

But something has clearly got to give. “There can be health care in assisted living without making it feel like a nursing home,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

Family members tell of frightened and confused residents arriving unaccompanied at emergency rooms, unable to give clear accounts of their problems. Dr. Kronhaus recalls a resident with dementia taken to the local E.R. by ambulance; discharged, she was sent home by taxi. The address she gave the driver was her former home, where neighbors spotted her and called the police.

By contrast, the North Carolina woman with a history of falls is doing well.

Dr. Taavoni discovered that her hypertension medications were causing such low blood pressure that she fainted. Reducing the dose and discontinuing a diuretic, Dr. Taavoni also weaned the patient off an anti-anxiety drug she suspected was causing problems, substituting a low dose of an antidepressant instead.

The falls and the related emergency room visits stopped. Doctors Making Housecalls is still caring for her, and for most of the neighbors in her assisted living facility.