People rarely follow a doctor’s orders to the letter.

We often seek treatments that meet our preferences, and adapt them to our personal routines and responsibilities.

This isn’t necessarily a problem. A treatment you don’t (or can’t) follow won’t help you, so the odds are better if you pick one you can.

In addition, not every treatment works for everyone — sometimes the best treatment we have works for just one of 10 people.

These truths came to mind as I recently addressed my plantar fasciitis — an injury to the tissue in the underside of the foot causing heel pain and afflicting about 10 percent of the population. I’d unwisely been trying for about six months to ignore the condition in both my feet. I kept walking to work and standing once I got there (by choice — I have a desk job) despite the discomfort.

Predictably, this rigid adherence to my lifestyle caused only more harm. Yielding a bit to my screaming feet, I stopped standing at work and cut my walking to a minimum, swimming for exercise instead.

This helped, but not enough to heal fully. The pain diminished but didn’t cease. Clearly, I needed to bend a little more, but which way and how much? Those are questions medical science and doctors cannot answer precisely.

Although somewhat disappointing, this is also empowering. There are dozens of therapies for the condition. I prioritized those that were recommended by doctors and for which there is good evidence, and that I felt I could stick with.

Although sometimes more invasive approaches are necessary with some modification of activity, most soft tissue injuries heal themselves in time. For 90 percent of patients, nonsurgical approaches to plantar fasciitis heal in four to six months. After that, you are looking at years to a lifetime of maintenance to avoid relapse. “Treatment” is really “lifestyle change.”

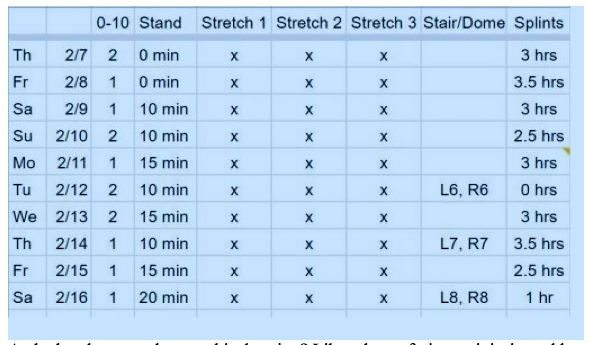

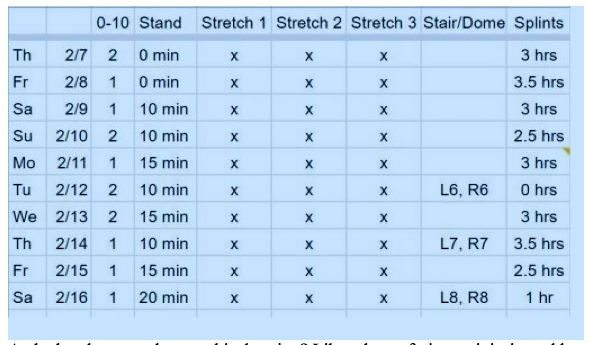

To help me commit to the long haul, I made a log to track progress. I gave myself credit each day I did what my selected regimen required. Not wanting to break my streak enhanced my motivation. I rated my pain and function daily. Healing is slow and often with setbacks, but it’s gratifying to look back over the weeks and months and see that there is, nonetheless, gradual progress.

The log I kept. I didn’t want to break my streak.

And what does one do over this duration? As with other soft-tissue injuries, addressing plantar fasciitis usually includes a mix of reducing and replacing injuriously repetitive body mechanics (which I had already done), calming inflammation or repairing tissue micro tears, and increasing flexibility and strength.

To choose an approach, I listened to my doctor’s advice. I also searched online and talked to friends who’d had the condition. And I consulted medical research to see if what was recommended had any validity. Finally, I targeted and stuck with treatments I felt I could fit into my life, always knowing that if they didn’t work, I could make a bigger change later. For example, though some studies support it, I did not pursue acupuncture because of the time involved in going to appointments.

There are several noninvasive or home-based remedies for planar fasciitis. Among the most common are orthotics, night splints (which hold your foot flexed to stretch the plantar fascia and Achilles’ tendon) and physical therapy (or at-home stretching/strengthening).

You don’t have to go to a doctor for foot orthotics. The ones that you can buy at the drugstore work just as well, research shows. CreditLars Klove for The New York Times

What does the research say about these? Orthotics help. Evidence shows that over-the-counter ones are just as effective as custom-made ones, and cost about one-tenth. They’re a set-it-and-forget-it approach. Unless they’re a bad fit, you won’t notice them, and there’s nothing to do to use them but stick them in your shoes. This was easy to work into my life. I bought some.

To provide additional support, you can also apply kinesiology tape, a stretchable athletic tape. A few studies suggest a benefit. I tried this, but only when I could not avoid long walks. At a few dollars per application to your foot, the tape is expensive. It also takes a few minutes to apply. Although perhaps a bit helpful, I didn’t perceive it worth it for daily use.

Night splints also work. Combining them with orthotics can accelerate healing. They can be difficult to sleep with, however. There are lots of types, but for each one there at least some patients who say they disrupt rest. I used them as much as I could (about three hours per night) and abandoned them as I felt better so that I could more easily sleep. To a large extent, lifestyle considerations (adequate sleep) triumphed over this therapeutic approach.

Standing on a wedge to help with foot stretching.CreditJim Wilson/The New York Times

The evidence on the effectiveness of stretching for plantar fasciitis is not strong. Nevertheless, it is frequently recommended, and I did find that it helped relieve discomfort in the short term. There are dozens of stretches. A study that compared two popular ones — a standing calf stretch and a seated foot stretch — found the foot stretch to be superior. Whatever stretching I did, I made sure to include that one.

At three times per day for about 10 minutes, a full stretching regimen takes considerable time. To fit it in without much disruption, I often did the foot stretching under the table during meetings and on conference calls. As for the calf stretch, I could do some of it while brushing my teeth or waiting for the train during my commute.

Trigger point therapy — massage, basically — can also help. If nothing else, it feels good. I threw that into my therapeutic mix, too, working my feet with massage balls as I typed and my calves with my hands as I read.

Finally, there’s strengthening. Here, there is good evidence that some approaches are very helpful, including a heel-raising variant previously described by The Times. It’s very tiring and time consuming, particularly if done according to the clinical trial (three or more sets per session), and requires a step off which to hang one’s heel.

The “short foot” exercise — pulling your toes toward your heels and arching the foot upward — may also be helpful. It requires no equipment and can be done surreptitiously anywhere. Now pain free, I’m doing both. I brought a yoga block to work so I could do heel raises during calls.

There is a lot of gray area in medicine. This mix of approaches worked for me, in large part because I found a way to fit its elements into my day, abandoning those I could not. Your approach — for this or any condition — may be different from mine. But one similarity may be that it is shaped not just by medical science, but also by the realities of life.