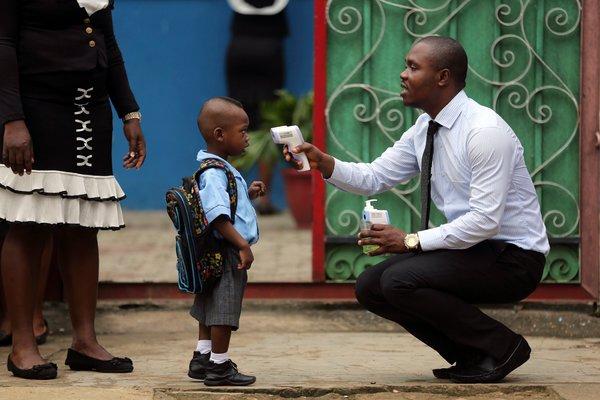

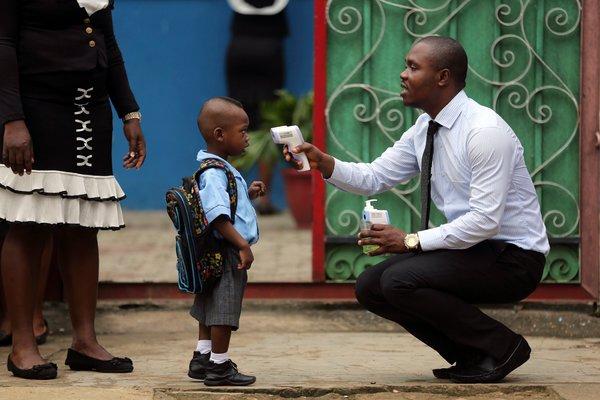

A school official taking a pupil’s temperature as school reopened in Lagos, Nigeria, in 2014 amid an Ebola epidemic. Nigeria’s successful containment of the outbreak was a public health success.CreditAkintunde Akinleye/Reuters

In so many domains, life is improving across the world.

It doesn’t always feel that way. In surveys, Americans overwhelmingly believe that world poverty is getting worse or staying the same (it’s getting much better). And they tend to underestimate, by a wide margin, the percentages of children in the developing world who are receiving vaccines.

Public health campaigns have been a big reason for major improvements, but urgent priorities remain.

Big challenges, and successes

The biggest area of need is probably in infectious disease prevention and treatment.

Devi Sridhar, a professor of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, said we need to focus on respiratory diseases.

“Childhood pneumonia is the leading infectious cause of death in under-5 children and kills more kids than malaria and diarrhea combined,” she said. In 2016, the disease killed an estimated 880,000 children, most under age 2, deaths that could have been prevented with vaccination or antibiotics.

But there has been progress in the fight against some other major killers.

Ashish Jha, a physician with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, said there have been major drops in the mortality of children under 5 (down more than 50 percent in the last three decades), and he pointed to other encouraging advancements:

-

the halving of deaths of women at childbirth

-

significant decreases in death from malaria

-

a turnaround in the H.I.V. epidemic

-

increased life expectancy in every country

Funding science research has led to new therapies, and global funding programs like Pepfar in the United States have made those medicines widely available, Dr. Jha said. Pepfar, begun under the administration of George W. Bush to combat the H.I.V. epidemic, says it has saved more than 16 million lives, primarily in Africa.

Establishing regional organizations to respond to outbreaks is also important, “as the 2014 to 2015 West African Ebola epidemic taught us,” said Peter Piot, a physician and director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The introduction of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2017 “marks an important step toward strengthening capacity and preparedness across the continent,” he said.

Some investments may not even seem to focus on health. Dr. Jha singled out girls’ education as the thing he’d invest in first. “Beyond its big effects on economic prosperity, it also leads to smaller family sizes, lower infant mortality, more stable families and communities, and likely lower levels of disease burdens like H.I.V.”

Improving health care systems can be crucial. Shoddy ones can actually cause harm — never mind failing to heal the sick. A 2012 study in Health Affairs showed that in rural areas of India, two-thirds of health professionals had no medical qualifications whatsoever. Incorrect diagnoses and treatments were more common than correct ones.

The downsides of Western ways

In some cases, the West may be hurting, not helping, the health of developing nations.

Dr. Piot said sustained action was needed “to tackle growing epidemics of obesity and diabetes.”

The New York Times reported on a practice, with roots in the West, in which nutritionists in developing countries take money from food giants. These international food companies have formed some alliances with scientists and government officials. In some of these countries, obesity is now common as American-style eating habits gain popularity.

Nearly all the experts we talked to agreed that cigarette smoking was a major problem. Dr. Piot said, “We need an all-out effort against smoking.”

In the United States, rates of cigarette smoking recently have fallen to a record low. But as smoking rates have declined in many Western nations, some companies have sought to maintain access to fast-growing markets in developing countries by working to limit antismoking laws, as The Times has reported.

As in the United States, antibiotic overuse and abuse cause problems in the developing world. Dr. Sridhar said, “Here public health investment does not necessarily mean health system investment — it also means investment in regulating agricultural (and food production systems) and effluents from pharma factories.”

How wealthy countries can help the most

Some months ago, we illustrated that while public health has phenomenal returns on investment in the United States, America puts relatively few dollars into it. We then asked experts about the biggest remaining U.S. priorities. (Readers chimed in, too).

Developing nations have differing needs. Poverty is obviously linked to the politics of those nations — whether they have democratic and stable institutions. Beyond supporting those institutions, what else can the West do to help?

Dr. Jha said we could assist in funding the development of drugs and diagnostic tests for diseases threatening poorer countries to a greater extent than wealthier ones, such as tuberculosis. He said helping fund the expansion of health care workers was another worthy priority: “Most developing countries have few public health officials and no programs to train them.”

Dr. Sridhar concurred. “First, fund and invest in research and development of neglected diseases and conditions in order to develop better diagnostics, vaccines and treatments.” She went further: “We need to continue to support institutions like the World Health Organization and the Global Fund to fight H.I.V./AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.”

She added one more item: “To manage the threat of drug-resistant infections which is already a major problem in poor countries, lobby all governments to adopt a binding United Nations agreement to regulate the use of antibiotics in humans, agriculture and the environment, particularly middle-income countries.” Such an action, of course, would help nations across the board.

A sense of hopelessness can sometimes weaken efforts to help the poor. The giant strides that have been made in recent years show things are far from hopeless, and point the way toward the possibility of more progress.