When Sam Fender, 22, a British singer-songwriter, released “Dead Boys” four months ago, a song about the suicide of a close male friend, he had no idea that so dour a subject would resonate so deeply.

The song, which exorcised his grief in a torrent of fidgety guitars, frantic beats and haunted vocals, has been streamed more than 3.5 million times on Spotify, and its video has about 850,000 views on YouTube. In December, he won the Critics’ Choice 2019 Brit Award (Britain’s equivalent to the Grammys).

While writing the song, Mr. Fender learned that 84 British men commit suicide each week; another friend killed himself after he finished recording the song. Mr. Fender blames those losses, in part, on “a world where men don’t feel they can talk about their problems, no matter how bad they are,” he said. “I started to question all the archaic ideas of what a bloke is supposed to be.”

On that score, he has plenty of musical company.

In recent months, a number of male rock musicians and hip-hop artists have released songs that rail against the most suffocating notions of what it can mean to be a man. And they’re finding a significant audience by doing so.

The new album by the brutalist British band Idles, “Joy as an Act of Resistance,” uses toxic masculinity as a sustained theme. It was a top 5 hit in Britain and has garnered some of the most awed reviews of the year. The Guardian ranked it No. 6 on its list of best 50 albums of 2018, writing that listening to it “often feels like purging yourself of the year’s toxicity in one pent-up blizzard of drums and guitars.”

As It Is, a neo-emo band from Brighton, England, released a single last June, “The Stigma (Boys Don’t Cry),” that attacks traditional male restrictions. The band’s current album, “The Great Depression,” has been streamed more than 13 million times on Spotify.

American artists have tackled the issue as well, including Tiny Moving Parts, an emo group from Minnesota, who released the album “Swell” last year. And Henry Jamison, 30, a singer-songwriter in Vermont, addresses what Rolling Stone magazine calls “violent interpretations of masculinity” in “Gloria Duplex,” an album due out next month.

The men, who all identify as heterosexual, say their writing is a direct result of the #MeToo movement and the dialogue about gender identity. “All these norms that we see aren’t normal at all,” said Joe Talbot, the lead singer and writer of Idles. “It’s a giant lie.”

For Mr. Talbot, 33, personal tragedy also brought the issues home. In 2017, his wife gave birth to a stillborn girl. “It was the most traumatic experience I will ever go through,” he said. “But I kept myself detached from my emotions. I thought it was stoicism. That’s not stoicism. It’s ignorance.”

It took months of therapy, and reading Grayson Perry’s 2016 book dissecting male tropes, “The Descent of Man,” before Mr. Talbot said he could “connect with other people and finally feel less lonely.”

Jordan Stephens, 26, a British hip-hop musician and actor, underwent a similar journey after a sudden breakup. “I had never experienced a loss of control like that,” Mr. Stephens said. “I was crying about stuff that had nothing to do with the breakup, stuff that I had put away for years, like my grandma dying.”

“I thought, something is wrong with men’s relationships to emotion,” he said. The experience moved him to write an essay in The Guardian in October titled “Toxic masculinity is everywhere. It’s up to us men to fix this.”

“For years, I had been a finger-pointing feminist,” he said. “I would call out every guy but myself. But the breakup and what happened around it put up a mirror to my own issues.”

The fact that music has become a key way for these men to explore these themes has deep antecedents. Elvis Presley blew away traditional gender roles by presenting himself as a hip-swinging sex symbol, a role more commonly reserved for women at the time. Transgressive stars of the 1960s, like Mick Jagger, and glam-rockers of the ’70s, like David Bowie, used androgyny to push back against gender constraints.

That dynamic has remained part of popular music ever since, though it has often been expressed just by teasing implication or as an act of provocation for commercial gain. See: hair metal bands like Mötley Crüe and Poison.

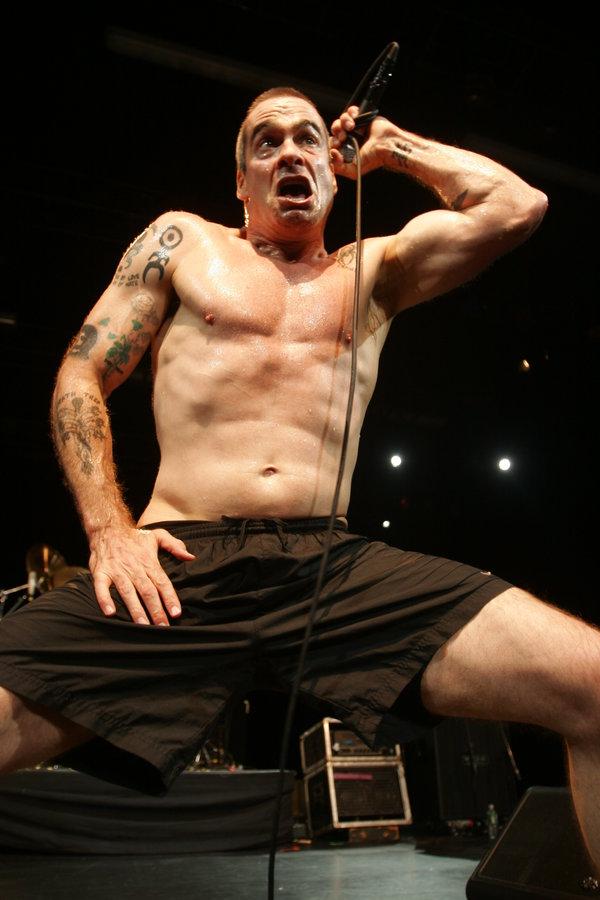

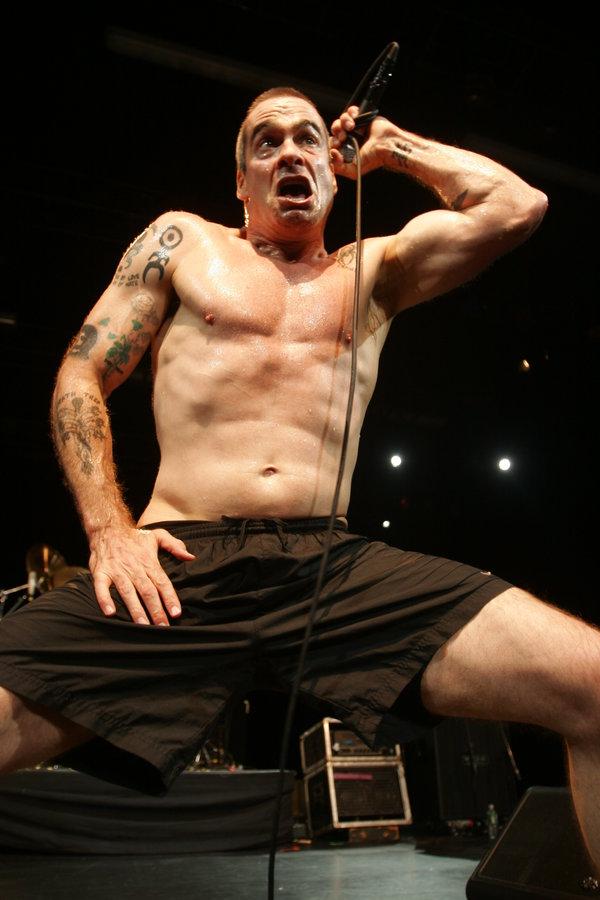

The current crop of maverick musicians takes a more earnest approach. One of their boldest precursors is Henry Rollins. Starting in the ’80s, his hard-core music, confrontational spoken-word pieces, and he-man persona consciously used virility to attack itself — something that Idles now does just as avidly.

Henry RollinsCreditRahav Segev for The New York Times

Mr. Rollins, 57, sees significant change between many of today’s musicians and those of his early days. “The entire scene is so less testosterone loaded,” he said. Younger musicians “have broken with the past. It’s a more open and truthful conversation we’re having now. I went to an all-boys school. We had gay teachers. Couldn’t talk about it. Gay students. Never mentioned.”

“The conversation about gender fluidity makes me feel old,” he said, but “I see I have to continually evolve.”

Indeed, musicians in their 30s already feel a cultural rift with peers in their 20s on matters of gender identity. “When I was in college 10 years ago, we were just horrible,” Mr. Jamison said. “People in their 20s are examining these issues in a way that feels very natural. They’re not going to have trouble if someone takes on a different pronoun.”

Still, the men worry that airing their issues may be seen as yet another case of men seizing the mic from women.

“I don’t want to in any way belittle the struggles of other people while talking about the struggles of a straight man,” said Patty Walters, 27, the lead singer of As It Is. “At the same time, toxic masculinity is real.”