An insidious scourge that has nothing to do with head trauma is ravaging retired N.F.L. players.

In the past few decades, the N.F.L.’s emphasis on the passing game and quarterback protection has led teams to stock their offensive and defensive lines with ever-larger men, many of them weighing well over 300 pounds. But their great girth, which coaches encouraged and which helped turn some players into multimillion-dollar commodities, leaves many of them prone to obesity problems.

In retirement, these huge men are often unable to lose the weight they needed to do their jobs. Without the structure of a team and the guidance of coaches for the first time in decades, many of them lose the motivation to stay in shape, or cannot even try, as damage to their feet, knees, backs and shoulders limits their ability to exercise.

This is a big reason that former linemen, compared with other football players and the general population, have higher rates of hypertension, obesity and sleep apnea, which can lead to chronic fatigue, poor diet and even death. Blocking for a $25-million-a-year quarterback, it turns out, can put linemen in the high-risk category for many of the ailments health experts readily encourage people to avoid.

“Linemen are bigger, and in today’s world, rightly or wrongly, they are told to bulk up,” said Henry Buchwald, a specialist in bariatric surgery at the University of Minnesota who works with the Living Heart Foundation, a nonprofit organization that provides free medical tests to former N.F.L. players. “Their eating habits are hard to shed when they stop playing, and when they get obese, they get exposed to diabetes, hypertension and cardiac problems.”

Many linemen say they were encouraged by their high school and college coaches to gain weight to win scholarships and to be drafted by the N.F.L., where a lot of players were required to become even bigger. In some cases, players were converted from tight ends to down linemen, and needed extra weight to play the new position. Coaches often leave it up to the players to decide how to gain weight.

Joe Thomas, an All-Pro lineman with the Cleveland Browns, said that as a freshman in college he ate every few hours to gain the 40 pounds he needed to get to 290 pounds. He gobbled burgers, frozen pizzas and large bowls of ice cream. “It was see food, eat food,” Thomas said.

The Living Heart Foundation has examined several thousand former players since it was formed in 2001 with financial backing from the N.F.L. players’ union. About two-thirds of those players — not just linemen — had a body mass index above 30, which is considered moderately obese. A third of those screened were at 35 or above, or significantly obese. The index, which is viewed as a general indication of weight relative to size, does not take into account muscle mass.

Linemen have been getting heavier, faster. From 1942 to 2011, they have gained an average of three-quarters of a pound to two pounds a year, about twice the average gain for all N.F.L. players, according to a study published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Another study showed that the average weight of offensive linemen ballooned 27 percent, from 249 pounds in the 1970s to 315 pounds in the 2000s, as the passing game evolved.

The consequences can be dire. A study published in The American Journal of Medicine found that for every 10 pounds football players gained from high school to college, or from college to the professional level, the risk of heart disease rose 14 percent compared with players whose weight changed little during the same period.

Plenty of linemen do lose weight. The former linemen Matt Birk and Nick Hardwick shed dozens of pounds after retiring and publicized their achievement. Thomas, who retired last year after 11 seasons with the Browns, gained roughly 30 pounds after entering the N.F.L. He has since lost about 50 pounds by eating less and eating healthier.

“I reversed everything I was doing,” said Thomas, who weighed about 320 pounds in the N.F.L. “No more freezer pizzas before bed. I dialed back the carbs, added whole grains, couscous, quinoa.”

The N.F.L. and the players’ union, recognizing more must be done, offer retired players medical exams, health club memberships and other services. Dozens of retired players, for instance, get free health screenings at the Super Bowl.

Still, many players are unreachable, said Archie Roberts, a former N.F.L. quarterback and retired heart surgeon who started the Living Heart Foundation. “If you don’t guide players through it, they won’t show up. If we can’t get them to follow through, they won’t get the health care they deserve.”

Derek Kennard: Sleep Apnea

Many former linemen said they woke to the dangers of being obese when the Hall of Famer Reggie White died in 2004 of cardiac arrhythmia. White also had sleep apnea.

Linemen are prone to the affliction, in which a person’s breathing repeatedly stops and starts because the muscles in their neck press against the breathing passage as they sleep. This cuts off the flow of oxygen and wakes the player, often for a second or two. The continual sleep interruptions can make it difficult for those with sleep apnea to feel fully rested.

Former linemen have big necks, and as they age their throat tissue becomes flabby, so their tongues can block their airways, said Anthony Scianni, a dentist who runs the Center for Dental Sleep Medicine, which works with former N.F.L. players.

The lack of oxygen, Scianni said, stimulates the body to produce more sugars, which can cause Type 2 diabetes and lead to overeating and other problems.

Derek Kennard, a guard for 11 seasons with the Cardinals, the Saints and the Cowboys, has battled to reverse this cycle. He snored so loudly — a common symptom of sleep apnea — that his roommate in his last season asked for a different room. After Kennard retired in 1996, the years of sleep deprivation led to other problems. He ate poorly and gained 100 pounds. He took Vicodin to deal with the pain of his football injuries. The pain, lack of sleep and extra weight made it difficult to exercise. His cholesterol levels and blood pressure jumped. He would fall asleep behind the wheel while stopped at traffic lights.

“You’re not sleeping well, so your body is not healing itself,” said Kennard, whose son Devon is a linebacker for the Lions.

After his brother died in 2009, Kennard, who is 6-foot-3 and whose weight peaked at 465 pounds, sought help. He was tested for sleep apnea and was told he woke 77 times per hour. One episode of not breathing lasted 1 minute 32 seconds. Because he flips in bed as he sleeps, Kennard had trouble wearing the mask of a CPAP machine, which delivers continuous positive airway pressure and is the standard treatment for sleep apnea. He switched to a mouthpiece that kept his airways open. He now wakes just twice an hour, and sleeps about seven hours a night. His weight fell to about 350 pounds, and he stopped taking painkillers.

“A hundred pounds came off quickly because I had energy to do exercise,” he said at a conference for retired players in Phoenix, where he lives.

Kennard urges other former players to be checked for sleep apnea, and tries to convince them that wearing a mask does not make them weak.

“I had so much death in my life, I could see it in front of me,” he said.

Vaughn Parker: Overeating, a Constant Battle

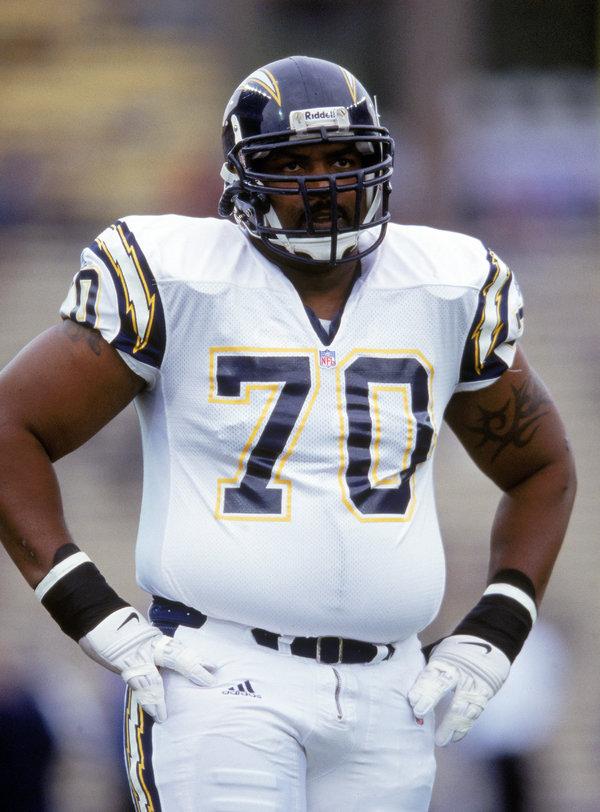

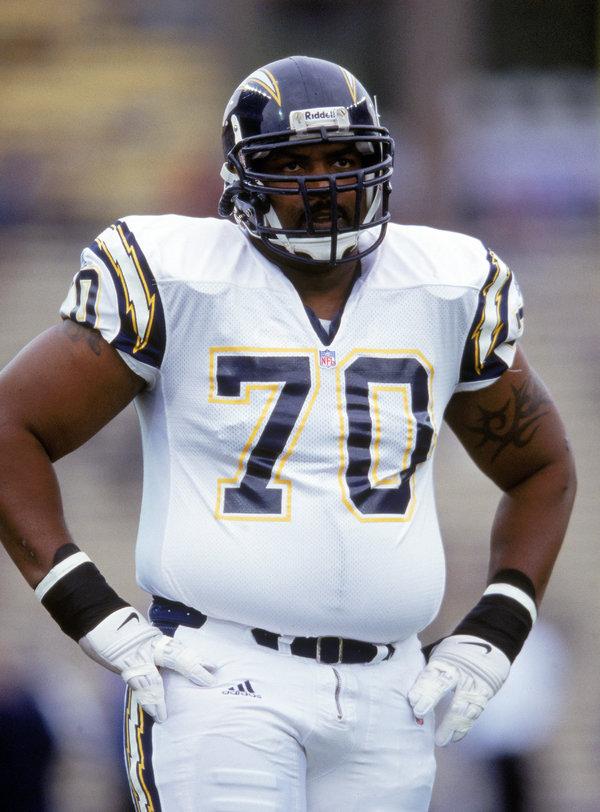

Vaughn Parker, a tackle who played 11 years, mostly with the Chargers, struggled with overeating, and after a dozen surgeries on his shoulders, ankles and triceps, he had a hard time exercising to shed weight.

He also got busy. Parker invested in real estate in San Diego until the market collapsed in 2008. He had two children, split with his wife and studied for an M.B.A., which he finished in May 2017. The stress led him to eat more, and before he knew it, he had added 90 pounds to his 6-foot-3 frame and weighed more than 400 pounds.

Vaughn Parker, who played 11 N.F.L. seasons, mostly with the Chargers, has struggled to get his eating under control.CreditOtto Greule/Getty Images

“Everyone has their cross to bear,” said Parker, 47, who also has high blood pressure. “For some people, it’s gambling or alcohol. For me, it’s food.”

In 2013, Parker received a phone call from Aaron Taylor, a former teammate, who encouraged him to work out with other retired N.F.L. players who received free gym memberships from the Trust, a group started by the N.F.L. and the players’ union to assist retirees.

Parker started driving 40 minutes to Carlsbad, north of San Diego, several times a week to EXOS, a high-end fitness club, where a trainer tailored workouts to his abilities and injuries. Afterward, the handful of former players discussed their progress and drank nutritional shakes. They learned about portion control and shopping for healthy food. Parker knew he had lost his best chance to become fit, which is right after retirement, but he tried to catch up.

His workouts were exhausting, but he stuck with the program, in part driven by the camaraderie of the other ex-players, and shed nearly 100 pounds the first year. “There wasn’t a day I didn’t sit at the edge of my bed and say I’m not going today,” Parker said.

Keeping the weight off has been a challenge. At home, he drinks protein shakes and eats made-to-order meals. But he also likes sugary drinks, and eating healthily on business trips has been tough. When he dines out with friends, he eats nachos, chicken wings and fried foods.

But the prospect of cascading health problems motivates Parker to keep exercising. He recently re-enrolled in a six-week training program at EXOS.

“How many 400-pound offensive linemen are walking around in their 50s?” he said.

Jimmie Giles: Avoiding Surgery, Managing Pain

Linemen are not the only players who need to keep the pounds on to play their position. Tight ends and linebackers often do as well.

That was true for Jimmie Giles, who because of his size and soft hands was one of the best blocking tight ends of his day. Nearly 30 years after he retired, Giles, who lives in Tampa, Fla., where he starred for the Buccaneers, checks in at roughly 350 pounds, about 100 pounds above his playing weight.

After 13 years in the N.F.L., ending in 1989, he had done lasting damage to his back, knees and feet. He had regular headaches, the result of about a dozen concussions. When he retired he took up golf to stay in shape. But the effects of his football injuries added up, limiting his activity. He had four degenerative disks in his back and no feeling in his right leg, and he had sleep apnea. His inability to exercise exacerbated his problems.

“It’s not like I gained 100 pounds right away,” he said.

To relieve the pain in his back, Giles received five epidurals a year, an ordeal he gave up when he started taking painkillers. But they can be highly addictive and caused sluggishness.

“That’s not living — that’s surviving,” Giles said in his family’s insurance office in Tampa.

About two years ago, Giles quit taking painkillers. He now receives cortisone shots instead. He said he does not even take aspirin “because I want to know when I hurt.”

“As long as I’m at a 5 out of 10 in terms of pain, I’m all right,” he added.

Giles, though, has put off back surgery for as long as possible, wary of the side effects. Every six months or so, he also receives radio frequency epidurals to deaden the nerves in his left leg, where he suffers shooting pain.

Giles’s father died from a heart attack, and his brother, who had congestive heart failure, is also dead. So Giles, who receives disability benefits from the N.F.L., regularly visits doctors to keep his high blood pressure and other vital signs in check.

Losing weight has been difficult. He rode a bicycle until it affected his prostate. Now he swims for an hour several times a week. He tries to eat moderately, and he avoids sweets and breads.

“It’s hard for him,” his wife, Vivian, said. “It’s not the food — it’s the injuries.”

David Lewis: Diabetes, Heart Condition

When David Lewis played linebacker in the 1970s and early 1980s, he was 6-foot-4 and weighed 236 pounds. Like many other players, he was pushed out of the game by injuries.

“I’ve had sprains, broken knuckles, hyperextended elbows, nerve problems in my neck, shoulders,” Lewis, 64, said. “I’d be guessing how much concussions I had.”

By about 40, he was receiving disability payments, and he has qualified for the 88 Plan, a league and union benefit that pays for medical care for players with dementia, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Unable to run or exert himself much, he now weighs about 300 pounds.

“As time went on, all the sickness started to add up,” he said.

The sickness includes Type 2 diabetes, a kidney ailment and a congested heart from hypertension. He receives iron transfusions to correct a deficiency. He takes a half-dozen pills each day.

Aside from taking medicine, combating those problems has not been easy. Lewis said he needed a knee replacement which should allow him to exercise more. But he said he could not have the surgery because of his heart condition.

He goes to a Y.M.C.A. to walk on the treadmill and ride a stationary bicycle. He has also tried to eat healthier, like dropping sausages in favor of oatmeal, egg whites and fruit.

This has helped him lose about 30 pounds this year and ease the stress on his knees and back.

Lewis knows he has to keep moving. Metabolically, the more weight you have, the harder it is to lose weight because the fat cells replicate, said Rudi Ferrate, a doctor who helps players with sleep apnea. “We’re designed to store energy,” he said.

Willie Roaf: Injuries Accumulate

Willie Roaf knew it was time to retire in 2005. After 13 years at left tackle with the Saints and the Chiefs, he was destined for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which he entered in 2012. Many of the 189 games he played were on unforgiving turf, and his body was breaking down.

Roaf, 48, tore his hamstring and had back and knee injuries, episodes of gout, a staph infection and periodic lymphatic swelling in his leg. Prediabetic, meaning his blood glucose levels were higher than normal, he was determined to keep his weight down and went to the gym after he retired. He weighed about 320 pounds, similar to during his playing career.

But within a few years, he became less mobile. Doctors told him he had spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal. In 2013, a doctor told him he had the back of a 70-year-old. He had surgery to relieve pressure on the sciatic nerves. He wanted to keep the pounds off, but working out was difficult.

“I can’t do anything more than stretching,” he said in his Florida kitchen. He takes medicine to prevent gout and to regulate his blood pressure, cholesterol, arthritis and uric acid.

His mobility has increased, and he has returned to the gym, where he does 30 minutes on the treadmill or elliptical machine several times a week. He takes about 7,000 steps a day, which he monitors with a Fitbit. He competes with friends to see who can walk the most. He tries to drink smoothies, eat fewer sweets and take vitamins.

“The more I move around, the better my numbers,” Roaf said.

Still, his injuries limit how much he can do, which has made it hard for him to lose 50 pounds to reach his target of 300 pounds.

“If it’s a bad day, I’ll just sit in the recliner and not go anywhere,” he said.

At the end of an hourlong conversation, Roaf’s Fitbit buzzed to remind him to get up and move. He got out of his chair, walked to a couch in the living room and sat again. The gym would have to wait.