“One issue that Laurencin did have with being taken seriously by, say, feminist art historians in the ’90s is that she was so feminine,” she said. “They just couldn’t get it.” After Laurencin’s death, her work fell into an especially peculiar trap: It was dismissed for its femininity and criticized for its supposed lack of feminist sensibility.

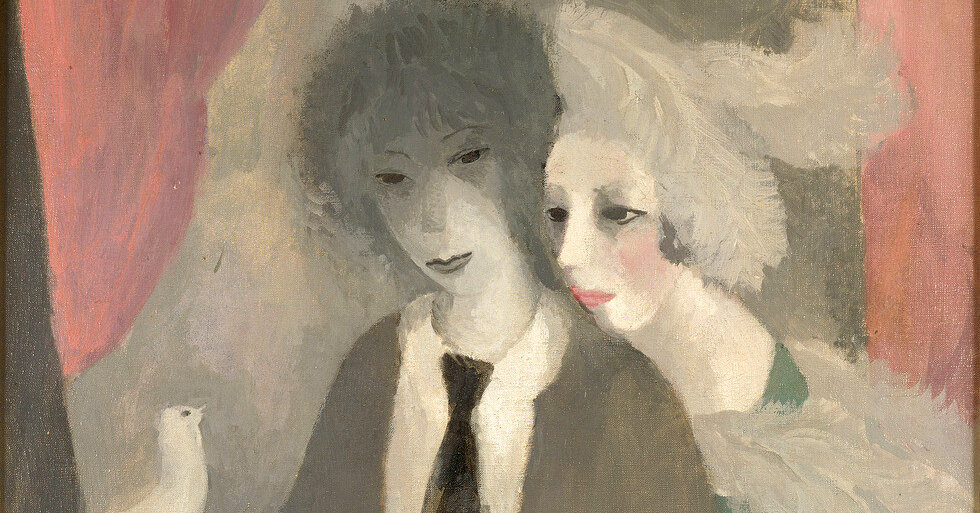

The intentional absence of men should speak volumes about her priorities, but Laurencin’s paintings aren’t shouters. Their figures whisper; they operate in secrets. “They’re very private works,” said Katy Hessel, an art historian and the author of “The Story of Art Without Men.” “Her figures share some intimacy. You’re actually looking at someone’s private world, someone’s interior world.”

“It feels like this incredible utopian world,” she said.

Professor Otto noted Laurencin’s ambition to find “a new visual language for feminine beauty that’s not the same as it was in the 19th century or with the Impressionists.” “She’s really striving to come up with a new aesthetic language to express female modernity and embrace the feminine from the inside,” the professor said.

Dr. Kang and other scholars argue that Laurencin’s Sapphic themes were ignored or overlooked for so long precisely because of their femininity. One scholar, Milo Wippermann, calls the neglect of Laurencin’s queerness a matter of “femme invisibility.”

“To see her from the queer feminine perspective, you see a type of queer feminine gender performance and you start to see what Laurencin was actually doing,” Dr. Kang said. A male collector like Albert C. Barnes, who created the Barnes Foundation in 1922 and acquired five of Laurencin’s works, “could think of her as easily feminine, but there’s a surrealist edge. And I think we’re now positioned to start to see that out, as opposed to ignoring it.”

Laurencin’s fantasy visions were not restrained to the canvas. She designed sets and costumes for theater and ballet; she illustrated books; she created decorative plates and wallpaper (Gertrude Stein bought several rolls).

And in each medium, Laurencin’s weightless, floaty, femme aesthetic never wavers. Laurencin was so firm about her style that she declined to repaint a commissioned portrait of Coco Chanel, after Chanel complained it didn’t look enough like her. But Laurencin had no interest in adhering to straightforward likenesses. She was interested only in creating an entirely new world.