the look

Figure Skating in Harlem helps young women of color see themselves on ice.

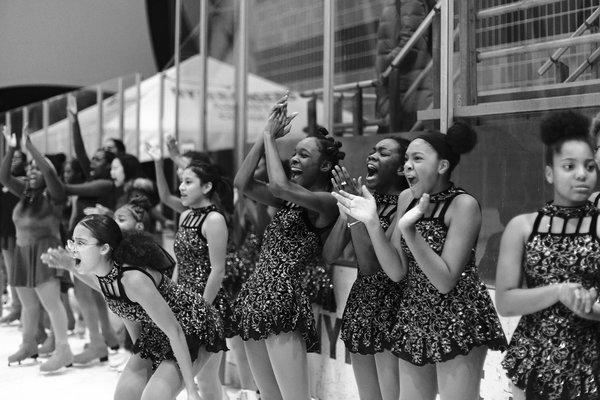

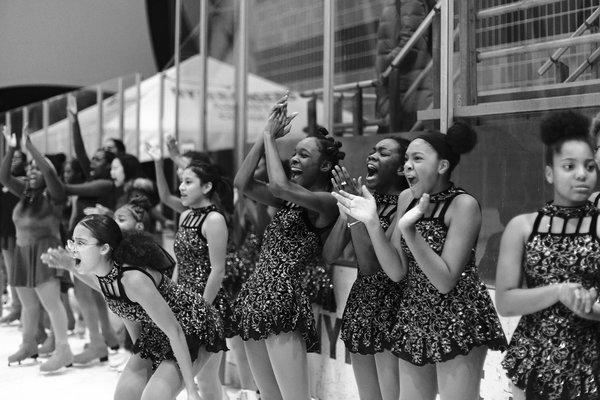

Figure Skating in Harlem instructs young New Yorkers in leadership, academic development and, of course, figure skating, a professional sport where women of color make up only a fraction of the field.CreditFlo Ngala for The New York Times

Picture a figure skater. Who comes to mind?

Maybe it’s Nancy Kerrigan spinning gracefully. Or it’s Michelle Kwan skating with confidence and ease.

It’s possible that it is Surya Bonaly or Starr Andrews — black women whose presence on the ice remains as daring as their performances — but professional figure skaters of color make up only a fraction of the field.

It’s a reality that feels far from mind at Riverbank State Park in Harlem, where twice a week, year-round, little black and brown girls glide and twirl across the ice.

“When I skate it just feels free,” said Jonni Carter, 10, who is part of an after-school enrichment program called Figure Skating in Harlem. “When you are gliding on the ice, the wind pushes against you and it just feels like you are flying.”

Figure Skating in Harlem provides young women of color with a space to build confidence, nurture academic success and use figure skating to understand themselves and the world around them. Sharon Cohen founded the program in 1997 after a group of parents invited her to teach their daughters how to skate. The initiative, she said, began as a “circle where girls could express themselves and what was going on in their life,” and evolved to serve over 170 girls between the ages of 6 and 18.

Figure skating, like most Olympic sports, has traditionally “been dominated by white people,” Ms. Cohen said. In 2017, the United States Olympic Committee reported that about 25 percent of their figure skaters were “people of color.” Much of the sport’s lack of diversity stems from its relative inaccessibility: Quality rink time can be hard to come by and competitive skaters can spend upward of $50,000 on training, equipment and costumes, among other expenses.

Figure Skating in Harlem does not bill itself as a training ground for future Olympians. Instead, the organization’s goals are to build community within the group and democratize what is considered an individualized, competitive and at times isolating sport.

When girls enter the program, they are divided into four groups by grade level: “Stars” are first through third graders; “Pros” are third through fifth graders; “Champs” are fifth through seventh graders; and “Leaders” are eighth graders through high school seniors.

The program has three core areas: figure skating, academic development and leadership development. The figure skating component includes both on- and off-ice instruction twice a week at skating rinks across New York City and, as of seven years ago, three synchronized skating teams that compete throughout the tri-state region. The academic component, which Ms. Cohen stresses is equally important, is designed to help the young women improve their skills in reading, writing and math.

Students in the program take a computerized assessment to measure their academic strengths and weaknesses. Then they are placed into small tutoring groups (usually made up of four or five girls) where they receive individualized instruction twice a week at the program’s home base on 125th Street in Harlem. The leadership component focuses on conflict resolution, identity and career exploration. Each week, the girls commit about 10 to 11 hours to the program, whose various elements work in tandem to support them physically, academically and emotionally.

“It builds up our self-confidence and our self-esteem,” said Jonni, who joined Figure Skating in Harlem at age 6. “Not like self-absorbed, but it makes us feel more confident in ourselves — that we can be more than what we thought we could be.”

Near the locker rooms at Riverbank State Park, she recalled a recent competition in Connecticut. “The ice was slippery, but that was the lowest I’ve ever lunged in my life, so it was technically an accomplishment,” she said. “I just got right back up, and I felt pretty good about participating.”

The other highlights of the day — it was also her 10th birthday — included sitting on the bus with her friends sharing cupcakes from Party City, listening to music and “watching creepy text stories” on an app called Hooked.

In addition to building and nurturing self-confidence, Figure Skating in Harlem directly addresses the underrepresentation of black women in skating. During the leadership and empowerment classes, the girls are taught lessons created by a team of social workers to help them negotiate their identities and contend with issues that affect young children, like bullying and the negative sides of social media. They also learn about successful women who look like them, both on the ice and off.

“Being a woman of color in a sport that is predominantly white has always been difficult in terms of identity,” said Vashti Lonsdale, the program’s director of skating. She named the professional skaters Surya Bonaly, Tai Babilonia and Starr Andrews as possible role models. “I think seeing Surya in particular being a rebel in her own realm and proving that you don’t have to be a stock standard looking person to be a great skater, it’s quite powerful,” she said.

Back at the rink, a little girl with pink gloves and a white hat attempted the beginning of a camel spin, a move that requires the skater to balance on one foot and extend her other leg backward. She fell onto her knees. Without pause she picked herself back up and glided into the arms of her two friends, who were waiting for her on the other side.

To the left of these girls, in a more sparse part of the rink, another skater lost her balance and started to wobble. But before she could hit the ground, another girl held out her arms and caught her.

“When I came to Figure Skating in Harlem, I realized how important it was that an African-American girl was ice skating and how out of the ordinary that was,” Raven Williams, 13, said.

When she started competing, she noticed that most of the time their team was the only one exclusively made up of black and brown girls. The other skaters “would kind of look at us, but when we actually beat them, it was the best look in the world because they don’t expect it from you,” she said.

Though a majority of the most prominent women skaters in the world are white and Asian-American, a quick internet search does turn up images and videos of black skaters consistently defying expectations. As I think about the girls, about skating and about freedom, there is one video that stands out most prominently in my mind. It is of the 16-year-old Starr Andrews at the 2018 United States Figure Skating Championships. She skates to Whitney Houston’s “One Moment in Time” and as she dances on ice, one of the commentators responds to Andrews’s early proclamation to “finish on the podium” as “a little bit ambitious.” But over the course of her five-minute routine, Andrews builds a momentum that matches the emotional cadence of Houston’s voice. She lands her triple toe loop and spins gracefully. The mood shifts and as Houston’s voice crescendos, tears begin to form in Andrews’s eyes. The commentator declares, in awe and excitement: “This is our future.”

Flo Ngala is a photographer, art director and former figure skater from Harlem. Lovia Gyarkye is on staff at The New York Times Book Review.