The speed of time is the speed of a clock, and goes by, we can probably agree, in a blur. The speed of fashion is seemingly that of light and is thus impossible to track.

This is the sense that can come over an observer of fashion’s increasingly hectic cycles. You begin a new year forgetting what you saw in the last. Creepy developments like Pinterest’s new Trends tool, which provides year-round, real-time trend data to the public are not exactly a help.

How about, instead, indulging in a little reflection? Why not slow down for a moment to consider the creativity that lies at the core of one of the largest global industries?

As another new cycle gets underway this week and scores of men’s wear shows roll out in London, Florence, Milan and Paris, I posed a question to some seasoned professionals: What stood out for you in 2019?

I asked because if there is anything that gets lost to the commercial imperatives of fashion, it is the desire among designers to create objects of both utility and beauty.

“There was really so much good design,” said Bruce Pask, the men’s fashion director of Bergdorf Goodman. The offerings he cited ran the proverbial gamut from Thom Browne’s intellectualized homage to that humble preppy staple, seersucker (which the designer rendered in the form of little boy shorts sets, skirts worn with codpieces and voluminous trousers with panniers at the hip), to Emily Bode’s poetic handmade garments patched from vintage quilts.

Yet for all extravagance of Mr. Browne’s vision and the modesty of Ms. Bode’s, what was most notable for Mr. Pask in the year gone by was the humblest of utilitarian garments: the chore coat.

“It was one of those items that became part of the zeitgeist,” Mr. Pask said of a boxy functional garment repurposed for an employment landscape in which people (not exclusively men) find themselves casting about for something comfortable and multiuse, a garment more adult than a sweatshirt yet less fuddy-duddy than a suit.

Mr. Pask said his favorite is a $320 patch pocket blue version from Le Mont St. Michel, a coat like the kind the photographer Bill Cunningham bought at French uniform supply stores and made his signature.

In the case of Josh Peskowitz, the fashion director of the online retailer Moda Operand, an average day’s work involves posting a series of self-portraits to Instagram, dressed in one coat more outlandish than the last. The series, titled “The Trench Coat Chronicles,” reached a peak when he turned up on social media clad in a singular trench from Francisco Risso’s fall 2019 collection for Marni.

“I look insane in it, but I love it,” Mr. Peskowitz said, referring to a garment that looks as if it had been excavated from the closet of Buster Poindexter, the rocker David Johansen’s alter ego.

“I often don’t like the idea of something being expensive and looking cheap,” he said. Of Mr. Risso, who showed the coat over pajamas, Mr. Peskowitz said, “Somehow he gets around this with his spirit of D.I.Y. and an attitude that is very punk.”

And as proof that Mr. Peskowitz’s admiration for the coat was not one of those abstractions that govern certain of fashion’s early adopters, he went all in.

“I actually bought a leopard print pony-hair trench coat for myself,” he said.

For Jim Moore, the author of “Hunks & Heroes: Four Decades of Fashion at GQ,” a compilation of pictorials he engineered as the magazine’s longtime creative director, 2019 was a year in which men’s wear found a sweet spot.

“Tailoring returned and the volume of clothes seemed right on,” Mr. Moore said in an email.

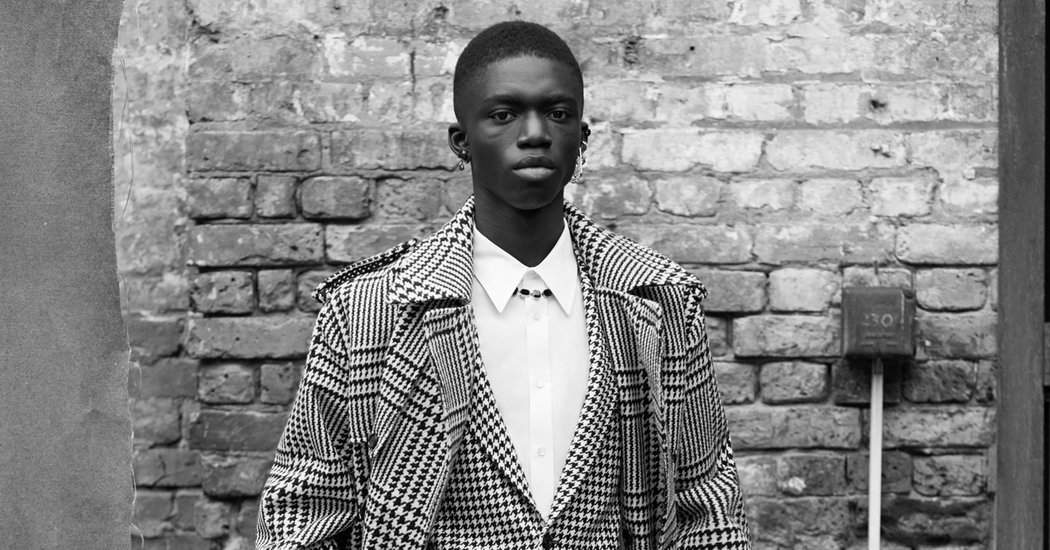

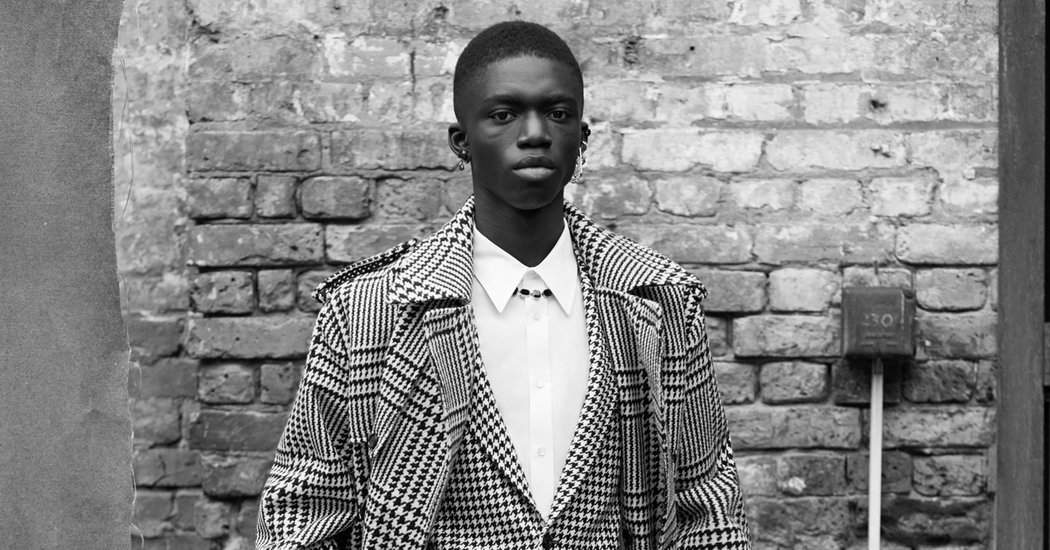

As an example, Mr. Moore cited a black-and-white houndstooth wool suit designed by Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen’s fall 2019 collection and worn under a similarly graphic wool coat in monochrome Glen plaid.

The subtlety of details like deep inverted pleats in the trousers and oversize patches on the coat pockets called to mind the exaggerated gentlemanly elegance of the Congolese dandies called Les Sapeurs, a contraction from the French for Society of Tastemakers and Elegant People.

“Men’s wear moments like this speak to a new generation in novel ways,” Mr. Moore said. “They don’t reek of old traditions at all.”

No one has ever accused Rick Owens of hewing to tradition. Yet what is indisputable is his sense of being part of a long creative lineage.

Elements of designers who have influenced him — people as disparate as Charles James and Larry Le Gaspi — pass through the complex matrix of Mr. Owens’s creativity, and yet the results seldom look as though they could have been produced by anybody else.

“My favorite look from 2019 is Rick Owens’s collarless, blown-up bubble, side-cross-zip B-1 bomber coat,” said Long Nguyen, a freelance critic who has spent decades observing fashion from its front rows.

“It was worn with a frayed asymmetrical T-shirt and leather and cotton combo pants that had the Owens signature,” Mr. Nguyen added, referring to innovation based on knowledge and a love of craftsmanship that, as Mr. Owens once told me, seems almost quaint in an age of computer-generated design.

That Mr. Owens does so in a way that rarely seems forced was a crucial factor in Angelo Flaccovento’s selection of a tossed-off Owens design as a favorite of the year.

“What I like about it is the color and the collarless shape,” Mr. Flaccovento, a critic for the Business of Fashion, said of a quilted long satin jacket that resembled the marriage of a mattress cover and a Happi coat. “In an era of abundance, I am all about less.”

“I also like the slight laziness of the look,” he said.

The obverse of that seeming offhandedness would have to be almost any design by Rei Kawakubo at Comme des Garçons Homme Plus. If there happens to be an easy way to get from Point A to Point B, Ms. Kawakubo will undoubtedly take a detour to difficult.

“I love that this look is full-on couture,” Nick Wooster, the retailer and Instagram influencer, said, referring to a long Comme des Garçons tailcoat-like jacket in gray tropical weight wool with flanged panels floating out from the hips.

Throughout her long career, Ms. Kawakubo has bridled at conformist inhibitions, whether those of gender binaries or so-called good taste. That hasn’t kept her from mining traditions — not infrequently those of Japanese court dress — to resolve her unease with the fundamental ungainliness of the human form.

“It is as though Rei Kawakubo and Charles James did a collaboration,” Mr. Wooster said of the jacket. “That one will definitely be on my back.”

It is hard to know who will be wearing the beaded shirt from Kim Jones’s fall 2020 collection for Dior Man, shown in Miami Beach in early December, but this much is certain: It’s not likely me, though I may wish otherwise.

And that is too bad. The Dior shirt falls into that category of garment so precious that brand representatives get coy when asked how much it costs. “Price upon request” is proof positive an object is not for hoi polloi.

It is consistent, though, with a direction Mr. Jones has pushed at every label at which he worked — that is, men’s wear produced at the level of haute couture. Finally the designer has landed at a house that can abet his ambition to capture a generation of moneyed men unafraid of fashion and conditioned by the rarity of the drop.

At Dior Mr. Jones can design clothes like this resplendent shirt, so offhand as to seem skate-rat generic, yet rendered at a level of skill commonly associated with the aristocracy.

The royal courts of our day have backboards and foul lines and hoops at either end. Even if I will never own the Dior shirt that took seven embroiderers 2,600 hours to create, I can amuse myself imagining it on a fashion-conscious baller like King James.

Looking is free, after all.

“Loewe, look six,” Tim Blanks, the fashion editor at large for The Business of Fashion, wrote in an email when asked to name the design object he dreamed about most consistently in 2019. “I feel oppressed by the debate on ‘masculinity’ that has infected men’s fashion.”

This is why he retreats in imagination from the “conflagration raging outside” to the mental comfort of a Loewe caftan designed by Jonathan Anderson and that Mr. Blanks rates the epitome of timeless cool.

“Generous, evocative, sensual, particularly so in suede,” Mr. Blanks wrote. It’s a garment that is male on a man (if he chooses that designation) and female on a woman (ditto) and enduringly seductive on either.

“You could wear it in 2020 B.C. or 2020 A.D. and never look wrong.”