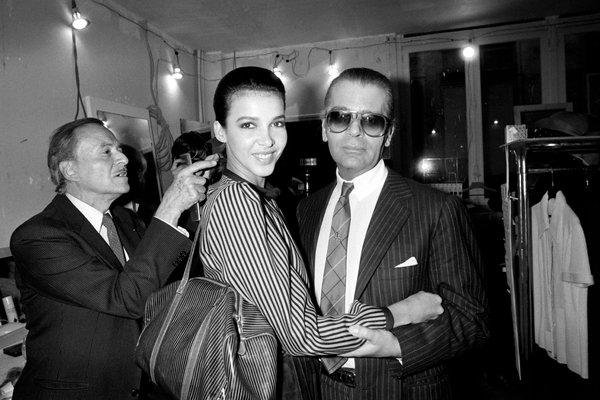

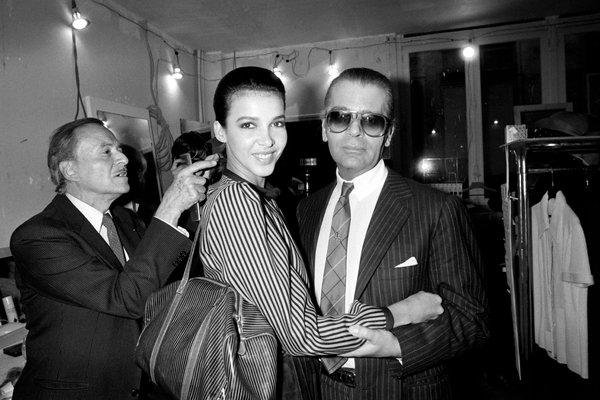

The designer Karl Lagerfeld backstage with a model before his spring 1983 haute couture show for Chanel in Paris. It was his first for the fashion house.CreditPierre Guillaud/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

When most people think of the word “designer,” they think of Karl Lagerfeld.

They think of his dark glasses and his weird little white powdered ponytail and his stiff white shirts and his black jeans. They think, maybe, of his black fingerless gloves and his silver Chrome Hearts jewelry. They think of his outrageous or amusing pronouncements, his grand gestures and his obsession with his cat, Choupette, who is one of his heirs.

They think of Mr. Lagerfeld’s silhouette, which appeared on everything from dolls to Coke cans. When it came to ubiquity, it wasn’t quite George Washington on the 25-cent coin, but it was close.

They probably think of all this even if they don’t know the Chanel or Fendi labels where Mr. Lagerfeld worked, or remember seeing Nicole Kidman and Pharrell Williams in his clothes, or realize that Anna Wintour wore custom-made Chanel each year when she hosted the Met Gala, in pictures that went around the world.

Six Decades of Karl Lagerfeld

24 Photos

View Slide Show ›

If they are fashion people, of course, they may think of more. They may think, perhaps, of the outrageous flower arrangements he used to send, bigger than anyone else’s (he did everything bigger than anyone else), and the scores of handwritten notes. They may think of his work, which ranged from the awkward (Chanel snowboards and boxing gloves) to the sublime (an “eco-couture” show that was an ode to the natural world, wherein he somehow managed to use wood as a fabric).

They may think, of course, of the show sets: the iceberg, trucked in from Sweden and then trucked back again; the supermarket; the rocket ship. If they have long enough memories, they may think of the fan that was once his signature accessory.

But whoever they are, there is little doubt that over five decades, through presence and attrition and volume and a willingness to put himself out there — through sheer force of mind, maybe — Mr. Lagerfeld became the emoji in everyone’s mind that stood in for the job. He died on Tuesday in Paris, Chanel announced.

As much as all the work, and the model for how to revive a heritage house the way he did with Chanel, that is what he gave us: an image of what “designer” means.

Now, of course, the job has changed. Designers have become creative directors or chief creative officers, and they are fluent in ROI and SKU. But that wasn’t Mr. Lagerfeld.

Rather, he was the man with the sketch pad, erupting with ideas in the ivory tower of material artistry, and we forgave him his trespasses in the name of the muse. Or muses.

Because, let’s be honest, he trespassed a lot.

He offended people right and left, making as much of an art out of the cutting aside as the perfectly cut double-face gown. He said mean things about Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, whom he drew hanging out with Hitler; the actress Meryl Streep, whom he falsely accused of asking for money to wear a Chanel dress to the Oscars; and the singer Adele, whose weight he criticized.

Three years ago, when I ran into him not long after a Gucci show in which Alessandro Michele, deep into his much-heralded reinvention of the brand, had referenced the somewhat obscure French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, Mr. Lagerfeld rolled his eyes and snorted and said, “Do you think he knows Gilles Deleuze?” The implication being that he, Mr. Lagerfeld, did not think so — because “I know Gilles Deleuze.” Of course he did.

He spent what seemed like let-them-eat-cake amounts of Chanel’s money on his sets during the global recession (though he also helped preserve and show off the work of the specialty ateliers — like the feather and embroidery houses — which easily could have been lost to history and industrialization). He judged and knew he would be judged himself, but he didn’t care. Rather, he embraced it.

This was a man, after all, who invented the haute fourrure show for Fendi — one full of clothes that were mind-blowing in their intricacy and invention — when fur itself was going determinedly out of fashion. Let the animal rights campaigners drive blood-spattered vehicles outside the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées while, inside, he took three standing ovations. He had no interest in being politically correct. At least when he was upsetting people, they weren’t bored.

It’s a strange thing to say, in the context of the multiple collections, the insane productivity, the omnivorous curiosity, the endlessly erudite references, the acres of satin and chiffon made glorious over the years, but one of the most extraordinary things about Mr. Lagerfeld may have been that he never apologized.

In all the hagiography that happens after a death, it should not be glossed over. Not just because it was part of who Mr. Lagerfeld was, in fully resplendent and sometimes ugly humanity, but because it is part of what marked him out as belonging to a different time.

Karl’s World

23 Photos

View Slide Show ›

It was a time in which proclamations were issued and edicts handed down from on high. It was before “dialogue” or “co-design” or any of the things we now consider the wave of the future, and before the constant stream of mea culpas issued on social media, where brands and individuals seem to be endlessly wrong-footing themselves. Mr. Lagerfeld didn’t want to go to business meetings or be bothered with quarterly reports or budgets. Often, it didn’t even seem like he had a budget. Or if he did, he ignored it (which is partly why he was the envy of so many other designers).

He prized the “freedom” — his word — of being left in his own world, with his atelier and his muses and his books and his Birman and his imagination and his ideas. He may have been heralded as a paragon of fashion modernity with his iPhone and his 300 iPods (this is, after all, an industry in which some chief executives still don’t use email), but in this, at least, he was resolutely old-fashioned.

It may be what we really mean when we say that his death signals “the end of an era.” It is the end not just of his reign, or that of his professional generation (Yves, Valentino and Co.), but of a certain idea that has lived in the public mind, far beyond the fashion sphere, of what it means to be a designer.

He outlasted almost all of his peers, who were lost along the way to the pressures of the changing industry, or disinterest in the spotlight, or the current conventional wisdom that 10 years is the longest any person should be in charge of a brand not his own. But even though Ralph Toledano, president of the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, called him “immortal,” soon we may all find that in fact, Mr. Lagerfeld really was the last of his kind.