Here is everything I knew about Mafolie before I went to the Caribbean island of St. Thomas in January: It was one of the original hilltop estates, given to my grandparents by my great-grandfather as a wedding present in 1936. The views, of Magens Bay to the north and Charlotte Amalie harbor to the south, were supposedly among the most-acclaimed in the Caribbean.

When my father was a child, the estate was 42 acres, but when his parents divorced, he returned to the mainland with his mother and didn’t go back, or see his father, for 25 years. When he did return, in July 1973, he had a Ph.D., a wife and a baby daughter, and the estate had been subdivided. My grandfather had managed to keep the original house, the Great House and two acres. We went back the following summer, when I was 3, and that is the last time any of us saw Mafolie.

My father is a university professor, a scientist skeptical of what he calls my “humanist love of place.” And yet he was the one who kept a framed pair of maps of St. Thomas, one of the biggest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, on the wall behind his dining room chair all the years I was growing up. He is the one who said the view from Mafolie had been described as the “eighth wonder of the world,” and told me about my grandfather playing horseshoes in the evening, his cocktail in a glass the shape of a bud vase so it could be slipped into his shirt pocket. I share my father’s deep love of his second landscape, the Connecticut River valley, but this first, tropical place was a mystery to me.

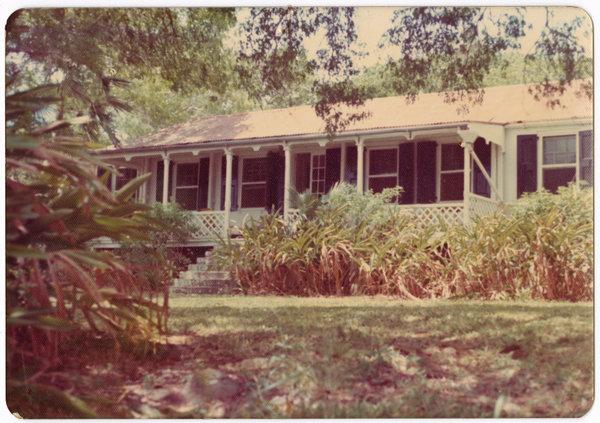

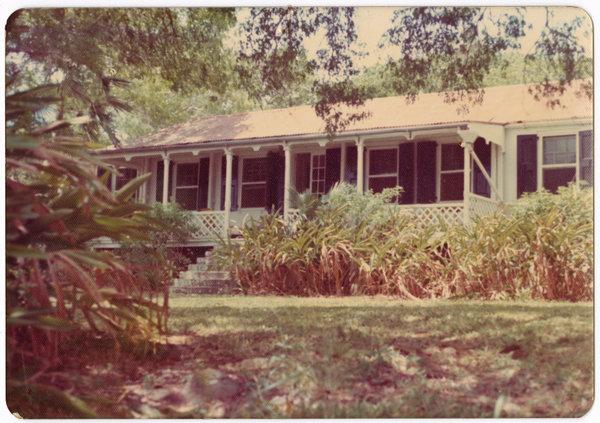

The south side of the Mafolie Great House in 1974. The house was subsequently torn down. CreditCourtesy Jessica Kane

The name Mafolie is from the French and means “my madness, my obsession.”

What is a daughter who grows up to be a writer to do but go and see for herself?

I stayed at the Mafolie Hotel which was built precipitously into the hillside below the original 42-acre estate when my father was little. It’s a compact place, more vertical than horizontal, with rooms and terraces across five levels, all beautifully landscaped, and a view of Charlotte Amalie harbor as magnificent as the one from the private houses above it. The hotel came through the hurricanes of 2017, Irma and Maria, relatively intact, and for months afterward housed relief workers and members of the Army Corps of Engineers. It has now fully reopened to tourists.

The first thing I did after checking in was spread the map of St. Thomas my father had given me on the bed, smoothing out the wrinkles from the suitcase, as if preparing for the final leg of a treasure hunt. In a way I was.

I was painfully aware of how little I knew about my grandfather, Frederick C. Dixon. A Quaker from Pennsylvania, he had settled on St. Thomas in 1930 after a few years working aboard a ship. He became a teacher, the principal of St. Thomas High School, and then director of education in short order. He was white, on an island where three-quarters of the population is black. Given the colonial history of the island, I was uncomfortable not knowing what his views on race had been.

Also, the Mafolie Great House was gone. When my grandfather died in 1989, the Great House and remaining two acres became the property of his second wife. When she died in 1995, she left the property to her daughter from a previous marriage, and no one in my family knew what had become of it. I had only recently discovered that in 1977 my grandfather applied to have the house listed on the National Register of Historic Places, an application that was approved in 1978. The listing describes Mafolie as once being part of Catherineberg, a sugar plantation. It was also listed on the Virgin Islands Inventory of Historic Places.

But we knew the Great House was gone because when it was leveled, sometime in the early 1990s, a neighbor gathered some things from the rubble and sent them to my father. Among the items: a leather address book, my grandfather’s Humane Society of St. Thomas membership card, some old photographs and an empty black wallet.

Whatever stood there now, I wanted to see it.

Finding connection at a namesake hotel

At the Mafolie Hotel, the friendliness of the staff was infectious. First names were shared and remembered immediately and I very quickly felt as if I’d known everyone — staff and other guests — much longer than I had. This charming warmth and the beautiful view make the hotel the kind of place where even locals come to have a drink at the bar.

The first night I met two of them, Lucy Serge and Diane Holmberg. “Oh, the island always brings you back,” they said when I told them why I was there. I thought it was a quaint idea. Lucy told me she would contact a friend of hers who might be able to help me with my research. That would be great, I said, if it worked out. But I really thought it wouldn’t.

I spent the next morning exploring Charlotte Amalie. Everyone I talked to mentioned how good it was that the island was green again and that tourism was returning — four to five cruise ships in the harbor every day — but if you looked carefully the signs of devastation weren’t hard to see. Mangled gates and broken walls and steel-reinforced columns holding up nothing. There were piles of debris here and there, and many trees had the dead branches of other trees wedged into them, blown there by the hurricane-force winds.

That afternoon Lucy’s friend, Juliette Creque Scobie, called me. Her father’s family’s history on the island went back hundreds of years and her mother had owned an old house in Misgunst, the estate right next to Mafolie. Juliette offered to help me find my grandfather’s property. At one time she’d worked for the Chamber of Commerce and had shown journalists and others around the island. But this was something she hadn’t done in more than 30 years. “This is interesting to me,” she said. “The island is obviously in your blood.”

She picked me up that evening and we drove up the road from the hotel. At the top of the hill on the right, there are two gates for Estate Mafolie, north and south. I didn’t know which property had been the site of the Great House, so we were at a loss and we were fast losing the light. We tried the Lower Road through the south gate first, but the views didn’t align with the photographs I had, a few from my father’s childhood in the 1940s and some from our visits in the 1970s.

We drove back to the entrance and took the Upper Road through the north gate. The vegetation was lush and the houses stood back from the road, sometimes behind their own gates, so it was not an easy neighborhood to navigate. We hadn’t gone very far when I saw a house on the left in ill-repair and so overgrown it seemed like it could have been abandoned. It looked a little bit like the house in my photos and for a moment I wondered if Mafolie hadn’t been knocked down after all.

Juliette parked and we went up to the gate, which was not very big or grand. It was also unlocked. Determined to solve the mystery, I rather uncharacteristically pushed it open and stepped onto the property. I was walking around the front of the house when Juliette called, “Inside! Inside!” which is, I learned after my heart stopped racing, a typical way of approaching a house on the island. A man called, “Who is it?” from an open window, and I tried to explain why I was trespassing.

“I’ll be right out,” the voice said, and a few minutes later, Bill Demetree came outside and asked me to repeat my grandfather’s name.

“I knew him,” Bill said. “It was a travesty when they knocked the Great House down.” He said travesty with great force.

I asked him if he could show me where it had been and Bill walked us slowly, on somewhat unsteady legs, to the edge of his property. He pointed to a gate slightly up the road and off a spur to the right. “That’s number 8,” he said. “Where your grandfather lived. But if you look through it now you won’t recognize anything.”

I ran up there while Bill and Juliette chatted about hurricane-related insurance problems. This gate was much bigger than Bill’s, with proper stone columns and wrought iron, and lots of signs announcing that the area was under 24-hour surveillance. It was dusk now, but I snapped a few pictures anyway. If they were dark and mysterious, it seemed appropriate.

With the sounds of a tropical night all around, Bill told us that the Great House was knocked down soon after my grandfather died, but years passed before two buildings housing several multimillion dollar condos were built on the site.

“How?” I asked.

Bill shook his head. He said at least the developers had left some of the old trees.

A chance meeting and new knowledge

The next afternoon, Juliette drove me to Magens Bay, where my young parents had taken me swimming as a toddler and afterward we went to a restaurant called Hook, Line and Sinker for lunch. We were waiting for our food when suddenly Juliette stood up to hug two women who’d come in. One was Lillia King, the daughter of Cyril E. King, the second elected governor of the island for whom the airport is named. The other was Cleone Creque, Juliette’s half sister who had served as a senator in the territorial legislature of the Virgin Islands. They marveled at the coincidence of bumping into each other just now and Juliette explained why I’d come to St. Thomas.

Cleone said, “Frederick C. Dixon?”

“Yes,” I said, very surprised.

“The commissioner of schools?”

“Yes.”

“What did the C stand for? I always wondered.”

“Charles,” I said.

“Oh, that’s pretty,” she said.

Cleone and Lillia sat down next to us for lunch and here are some of the things Cleone said about my grandfather:

“He was very popular. He was one of us, very quickly.”

“He proposed a number of improvements to the educational system.”

“He was a breath of fresh air. He cared about the black children.”

“He is not forgotten.”

And then she looked at Juliette and said that their father and my grandfather had been good friends. While my grandfather was trying to improve the public schools (he helped establish the first teachers institute on the island), their father was responsible for giving the school bus contract to a nonwhite person for the first time.

Juliette and I looked at each other and ordered another drink.

“This was meant to be,” she said.

Back to the hilltop

My last morning in St. Thomas, I woke up early. I knew so much more about my grandfather, but I was still haunted by a dream I’d had of Mafolie the night I’d made my reservations for the trip. I was sitting on bleachers over a beautiful turquoise bay when suddenly the seats rose up and became a roller coaster. I don’t like roller coasters and so closed my eyes against the feeling. But with my eyes closed I couldn’t see the landscape. In the dream I was there but not there, unable to see what I’d come to see.

My flight home wasn’t until the afternoon, and though I didn’t know how I was going to get in, I decided that last morning that I had to try and see the place where the Great House had been, No. 8 Mafolie Estates.

I walked up the road staying as close to the shrubbery as I could. You don’t see many walkers on the hill roads because they’re narrow and there are no sidewalks — I’d been warned against it — but I was determined. When I came to the Estate Mafolie gates I punched in the code. I followed the Upper Road to the gate Bill had shown me and as I stood before it, I heard a hummingbird thrum past. I found it hovering near a red flower just inside the gate where it stayed a moment before flying on. In Connecticut, my grandmother and I had both loved hummingbirds. This seemed like — a sign? I sat down.

When a BMW appeared at the top of the drive, the gate started to open. The driver lowered his window, and I explained what I was doing there. He said I could look about the place, but the gate had closed behind his car, so he gestured at the foliage and said, “Just go around.”

He drove off and while I was trying to figure out what he meant, a woman came walking up the road. Her name was Susannah, and she turned out to be the BMW driver’s housekeeper. She said I could follow her, and so I did, into the foliage around the pillar on the right side of the gate. We stepped over uneven rocks and had to push back branches; this was her path to work. I told her there should be a proper path and she laughed. Susannah went inside one of the grand, two-story pale yellow buildings and I walked around the hilltop for a while. Then I sat down on the grass, my back to the buildings, my face to the Caribbean.

Here is what I wrote in my notebook: “I am on a terraced slope of lawn high above Charlotte Amalie harbor. There are old mahogany trees dotting the property that must have stood in my grandmother’s time. I’ve put my hand on them and said hello. A very old banyan tree stands on the north side, where the view is of Magens Bay, so that must have been there, too. The air smells of sun and jasmine. There is a constant wind, a little more insistent than a breeze. You hear it in the mahogany leaves. Every now and then a seaplane takes off over the harbor, sounding exactly as Dad described it. Every time one starts up, I hear his impression in the hum. I must have known that sound, too, as a small child here. An occasional rooster and the echoes of construction over the island are the only other sounds. I found Mafolie.”

My grandmother spent all the years I knew her trying to grow tropical plants in Connecticut. My scientist father admitted the sound of a seaplane taking off is wonderful to him in a way he can’t quite explain. And islands have always had a hold on me that my mainland childhood doesn’t quite account for. Mafolie.

In the taxi to the airport I looked back at the ridge line above Charlotte Amalie one last time and realized I could tell where the Great House had been by the trees, the old and twisted mahoganies left at the edge of the terracing.

The island always brings you back.

Jessica Francis Kane is the author of a novel and two story collections. Her new novel, “Rules for Visiting,” will be published by Penguin Press in May.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.