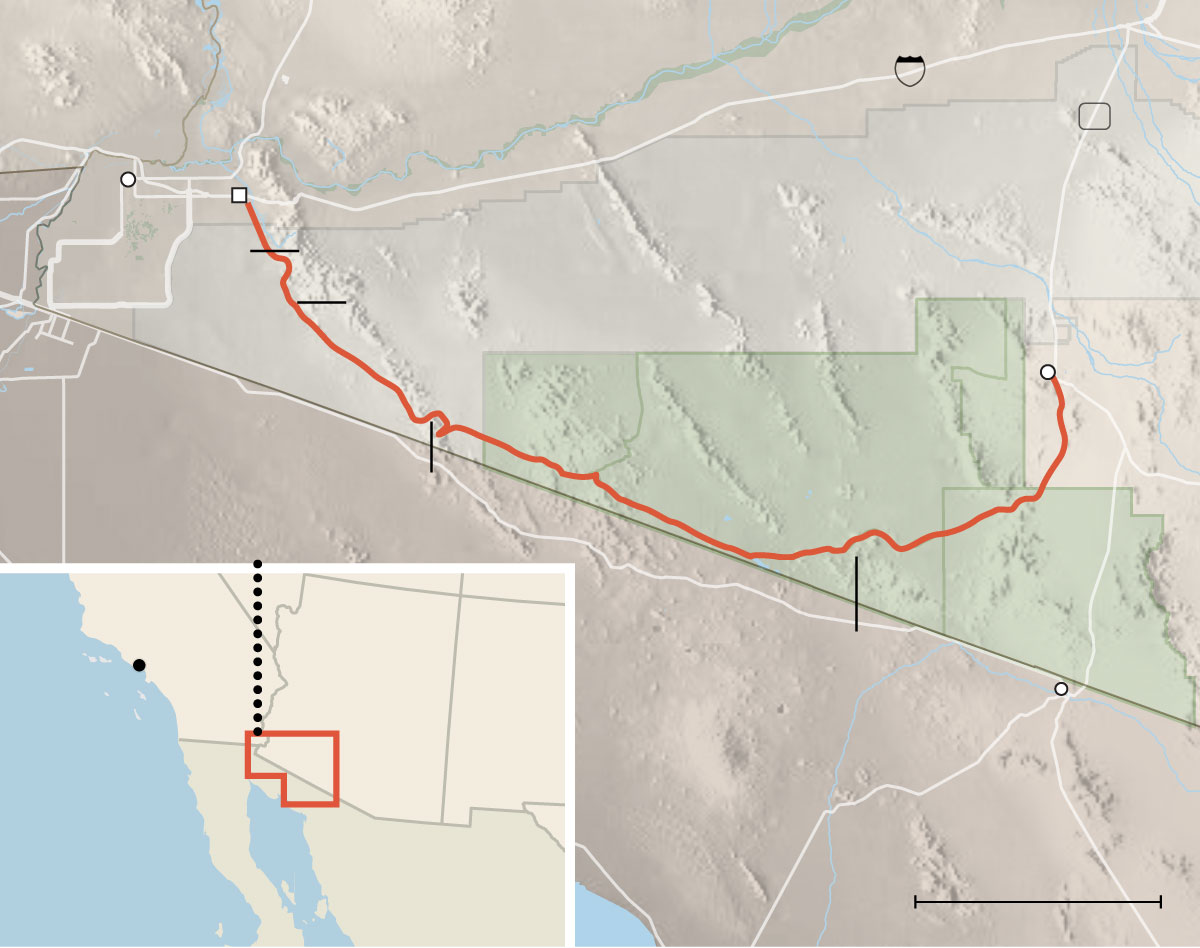

While filling out a permit application to drive El Camino del Diablo — a dirt road that cuts through 130 miles of saguaro-studded desert between Yuma and Ajo, Ariz. — I marveled at the hazards it warned I might encounter along the way, including “permanent, painful, disabling, and disfiguring injury or death due to high explosive detonations from falling objects such as aircraft, aerial targets, live ammunition, missiles, bombs, and other similar dangerous situations.” I might also stumble across warheads embedded in the ground, not to mention rattlesnakes.

Still, I knew from a previous trip that while the Camino del Diablo may feel like a death-defying excursion into forbidding territory, it’s actually quite safe. The road — which is on the National Register of Historic Places, and passes through the vast Sonoran expanses of the Barry M. Goldwater bombing range, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument — is surprisingly well maintained and no special skills are needed to navigate it. The scenery is vast and mesmerizing. Ocotillos sprout from arid basins, their spiky tendrils and bright red blossoms swaying in the breeze like some kind of weird desert anemone. There are sand dunes and lava flows and knife-edged mountains slicing skyward from the desert floor. Owls roost in saguaro cactuses, endangered antelopes browse sparse grasses, bighorn sheep leap among rugged crags.

I went in late March, hoping to see desert wildflowers in bloom. Though it’s possible to make the drive in one ridiculously long day, it’s better to go slowly, so I took three days, camping along the way.

The writer’s second campsite along El Camino del Diablo, in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.CreditMichael Benanav for The New York Times

A notorious reputation

The original Camino was an important trail between Yuma and Sonoyta, Mexico, and for centuries has been notorious as a route along which people die. Conquistadors, missionaries, prospectors, traders and others traversed it, beginning in 1540, usually heading to or from California. So many perished along the way, in this place that can feel as hot as hell, that it became known as the Devil’s Highway. Historians believe there may been more than 2,000 fatalities in the last half of the 19th century alone.

The mythos of death surrounding the route conveys the impression that it’s a risky thing to attempt. Temperatures can surpass 115 degrees, with ground temperatures reaching 180 degrees. Water is scarce and hidden in tinajas (natural cisterns), tucked out of sight in rocky clefts; the evaporation rate is 40 times the average annual rainfall.

The graves of previous travelers, including those of entire families, can still be seen near the road. And then there’s the tragic story of the so-called Yuma 14, documented in “The Devil’s Highway,” by Luis Alberto Urrea, which recounts the doomed journey of 26 Mexicans lost in this desert in 2001, over half of whom died of dehydration and exposure.

In truth, falling aircraft aside, the worst of the trail’s dangers can be mitigated by bringing jugs of water and exercising common sense. While high-clearance, four-wheel drive vehicles are required, you don’t need a monster truck — I went in my 9-year-old Toyota pickup with a decent set of all-terrain tires.

Still, it’s not a trip to be undertaken carelessly. You don’t want to get stuck in the middle of the desert, and if you are, you want to be prepared. Well aware that I was flouting accepted wisdom by traveling alone, I carried plenty of food and water, two spare tires and extra gas. I took comfort in knowing that if my truck did break down, I would likely be discovered by Border Patrol agents within a matter of hours, as a substantial length of the road runs within a mile or two of the Mexican border. Here, one has to work hard not to be found.

By the time a Spanish captain named Melchior Díaz led the first convoy of Europeans from Sonoyta to Yuma in 1540 as part of the Coronado expedition, Native Americans — including the Quechan, the Cocopah, and the nomadic hunter-gatherer Hia C’ed O’odham (Sand People) — had lived in this swath of Sonoran desert for thousands of years.

European explorers relied heavily on native guides to lead them successfully through the perilous unknown, from one watering hole to the next; among them was Padre Eusebio Kino, who made missionary and scientific trips along the Camino beginning in 1699, and drew its first maps.

There were several variations on the route. The shortest course offered the least water, which could have dire consequences. Thirst was less of a problem on longer trails, but those risked Apache attack. Faced with this choice, some believed the safest strategy was to go the long way in the hottest days of summer, when the Apaches tended to retreat to the mountains.

Traffic along the Camino peaked in the mid-19th century, as prospectors were lured across it to the Gold Rush in California. In the early 1850s, over 10,000 people, many from Latin America, made the difficult trek each year — it was during this time that the trail claimed the most lives and earned its diabolical name. While mapping the border in 1855, Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler noted that along the Camino “death has strewn a continuous line of bleached bones and withered carcasses of horses and cattle as monuments to mark the way.”

No one keeps track of exactly how many travelers the Camino sees today. The manager of the Cabeza Prieta refuge, Sid Slone, guesses that up to 1,000 people may drive its length each year. And Mr. Slone has never heard of any of them dying in the desert.

On the road

I embarked on the Camino from the Yuma side, passing through an opening in a wire fence on the edge of the community of Fortuna Foothills. A sandy washboard road unfurled into the 1.7 million-acre Goldwater bombing range. The sun blazed through a cloudless sky, but the temperature was comfortably in the 80s. Ocotillos, which look like plants that might have been designed by Tim Burton, swung their skeletal boughs in an eerie yet cheery welcome. To my right, signs alerted visitors in English and Spanish about the presence of unexploded ordnance and lasers in use. My left-hand view was framed by the serrated ridgeline of the Gila Mountains. This is classic Basin-and-Range country, where flat valleys lie between rows of rugged, uplifted mountains.

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Fortuna

Foothills

Barry M. Goldwater

Air Force Range

El Camino del Diablo

Cabeza Prieta Nat’l

Wildlife Refuge

TINAJAS ALTAS MTS.

papago MT.

Organ Pipe

Cactus Nat’l

Monument

Los

Angeles

Pacific

Ocean

Street data from OpenStreetMap

Fortuna

Foothills

Barry M. Goldwater

Air Force Range

El Camino del Diablo

Cabeza Prieta Nat’l

Wildlife Refuge

TINAJAS ALTAS MTS.

Organ Pipe

Cactus Nat’l

Monument

papago MT.

Los

Angeles

Pacific

Ocean

Contrary to images of deserts as lifeless wastelands, I found myself crossing a spectacularly complex ecosystem. The Sonoran is the most biodiverse desert in the world. This section of it alone is home to more than 275 animal species (not counting insects), and some 400 types of plants, including the saguaro cactus. Perhaps the most likable member of the plant kingdom, each saguaro appears to have a unique personality — depending on how their arms are posed, some seem to be waving hello while others stand guard, some are praying for mercy while others are high-kicking the cancan. Even better than driving past them is walking among them, taking time to gape at these elephantine cactuses that may live for 200 years. Thankfully, more than a million acres on either side of the Camino is federally protected wilderness.

Navigating with 1:100,000-scale United States Geological Survey maps, as well as the Goldwater range map, which can be picked up at the Cabeza Prieta office in Ajo or downloaded online, I aimed southeast. I was hoping to camp near Tinajas Altas, the most reliable water source along the Camino.

A set of 15 pools stacked one above the other, hollowed into the granite of the Tinajas Altas Mountains, these natural tanks can hold some 20,000 gallons of rainwater but are rarely full. From even a short distance away, they are invisible. According to the authoritative “Last Water on the Devil’s Highway: A Cultural and Natural History of Tinajas Altas,” the site is not only a crucial watering hole, but a sacred site for the area’s Native Americans. In past centuries, tribes came to hunt bighorn sheep; once the meat was taken, bighorn bones were ritually stacked along nearby footpaths and were sometimes ceremonially cremated.

I pulled my truck off a rocky dirt track that ran along the base of the Tinajas Altas Mountains and made camp as the sun was setting. Steep, ivory-colored walls of weathered granite rose behind me. To the east a raspberry-hued haze settled over the parched flats of the Lechugilla Valley and the Cabeza Prieta range. Night fell and Orion, his dog and their celestial companions emerged above. I was cooking hobo stew over a small fire when two headlights appeared in the distance.

Soon, a white pickup truck with a green stripe on each side came to a stop nearby. “Everything O.K.?” the border patrol officer asked. “I saw your campfire and thought it might have been a rescue signal, so I came to check it out,” he explained. It obviously wasn’t someone like me — meaning an American citizen with four-wheel-drive — that he thought might need rescuing. We were about three miles from the Mexican border, where it’s not uncommon for people crossing illegally to run into trouble and run out of water.

Undocumented immigrants — whether families or, more commonly, drug mules — have long been a fact of life on the Camino. The road itself is used as primitive sensor, as Border Patrol agents drive up and down it, scanning its sandy bed for footprints and other signs of human traffic. I spoke to several agents along the way; all told me that the flow of undocumented immigrants over this section of the border was inconsistent. “It changes all the time,” one agent said. “Now it’s very quiet.”

Knowing there may have been people walking north through the wilderness added an unusual element to this trip. I felt sure that if I was approached by migrant workers or a family, that the most they would want from me would be water and food, which I’d be happy to give. But I wasn’t sure whether a smuggler with a backpack full of weed or meth might be tempted to steal a truck from a guy alone.

Every agent I encountered, though, said that they’ve never heard of any problems or “negative interactions” between undocumented immigrants and travelers on the Camino. Anyone heading north, I was told, seeks to avoid all contact with “civilians” unless they are dying of thirst.

I grappled with the implications of enjoying a place while, at the very same moment, others might be struggling to survive in it. I’ve always found deserts, raw and elemental, to be the most existentially provocative (and ultimately satisfying) of environments; as a result of the border situation, this one inspires different kinds of questions than any other I’ve been in.

A land painted with color

The next day I entered the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, where wildlife protection has been remarkably successful at rehabilitating endangered populations of desert bighorns and Sonoran pronghorns — North America’s fastest land animal; in 2001, only 21 Sonoran pronghorns remained in the United States. Today, there are around 400.

After stopping for a couple of short hikes, including one up a canyon to find Tule Tank — another historically important water source — I took a seven-mile side trip up a rough road to Christmas Pass, looking for the bighorns that are sometimes found in that area. With no luck, I returned to the Camino to camp that night in the middle of nowhere, drawn to a spot by a particularly intriguing saguaro. Though there are established campsites with picnic tables in two places in Cabeza Prieta, camping is allowed anywhere within 50 feet of the road and a quarter-mile away from water sources, preferably where someone has camped before.

The next morning I got up early. Knowing that rattlesnakes are prone to warming up on the road, I kept an eye out, hoping to see one up close but from the safety of my truck. Though the desert to the west had been speckled with flowers, from bright yellow brittlebush blooms to scarlet-petaled chuparosa shrubs, I was entering a land painted with color. This year’s so-called superbloom had apparently made it all the way out here. The blocky basalt of the Pinacate lava flow shimmered with desert sunflowers, while white primrose and prickly poppies, yellow marigolds, purple sand verbena, and more, burst from the Pinta Sands in random arrangements expressing a chaotic exuberance of life. In a gentle valley hewed between Papago Mountain and unnamed hills to the north, groves of saguaros stood with waves of orange globemallow lapping at their feet.

The spring bloom is difficult to predict, hinging on the timing and quantity of desert rains. It may begin as early as February and, with different plants blooming at different times, can last until late May. Though most of the cactuses hadn’t yet blossomed, I felt I’d been lucky.

With my skin, hair, clothing and truck interior coated with dust, and my left arm dark from driver’s tan, I entered Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in the afternoon. A Unesco Biosphere Reserve, it’s the only place in the United States where organ pipe cactuses grow wild. Since its southern edge runs just north of Sonoyta, it’s long been in the spotlight as an unforgiving obstacle course for undocumented immigrants, though their numbers have decreased dramatically over the last decade.

I wasn’t going to be seeing any of the park’s most popular sights, as the Camino wends through its isolated northwestern corner, between the imposing topography of the Growler and Bates Mountains. Since camping along the road here is prohibited, I had to satisfy myself with a late hike. As the sun slipped behind a distant ridge, the hillside before me was cast in deep shadow while the saguaros and wildflowers I walked among glowed in the golden light, creating an ethereal Sonoran wonderland.

Dusk absorbed the desert. The sky was awash in copper and violet and my body hummed with gratitude. I drove the last stretch of road into Ajo in a state of tired euphoria. For a while, anyway, all of the complicated questions evoked along the Devil’s Highway fell quiet.

If you go

Wildflowers may bloom along the Devil’s Highway as early as February, while most cactuses hold off until April, and saguaros typically wait until the last half of May. The worst time of year to go is the summer: Daytime temperatures are brutal, and the rare thunderstorm may make parts of the road impassible until it dries.

A high-clearance 4×4 vehicle is required; make sure yours is in good working order and has at least one full-size spare tire. Carry more water and food than you think you’ll need. There is no mobile phone service for nearly the entire length of the road.