In this way, and on account of the sheer number of wearers, there was always something populist about the brand. At the same time, of course, the British countryside idyll was traditionally a lifestyle reserved for a certain kind of person, namely someone white and Protestant. Designers like Hay, who draws on her Jewish heritage — her line was inspired, in part, by her Yiddish-speaking grandmother’s “frumpy New York aesthetic,” as she puts it — and Kika Vargas, Yuhan Wang and Sindiso Khumalo, who are all women of color, have found ways of subverting the aesthetic and its conventions and, in doing so, making it their own.

Khumalo, who is based in South Africa and references her Zulu heritage in her work with bright, sustainable fabrics, admires Ashley’s ability to “tell stories with her textiles.” For several collections now, Khumalo has been looking at portraiture from the late 1800s and early 1900s of Black women, including formerly enslaved African American women who had been freed and Black women in Europe, and notes that although their lives may have been very different from those of their white counterparts — the women Laura Ashley was referencing — aspects of their clothing, with “big, big, big shoulders and a lot of embroidery details,” Khumalo says, were often quite similar: “There’s an aesthetic of what people wear, and that goes beyond a specific racial group — it’s what society’s wearing at a time,” she says. For her, fashion, with which one can excavate stories and details otherwise lost to history, is a “tool for activism, but also a tool to talk about the Black African experience.” The London-based Wang, who’s known for her ruched floral columns, was trained in traditional Chinese painting as a child and says she has spent hours “sketching historical relics” at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Like Khumalo, she also believes that looking to the past can be a way of moving forward: “My futurism is based on the way we were,” she tells me. “There are always things worth rethinking. That’s where the future comes from.”

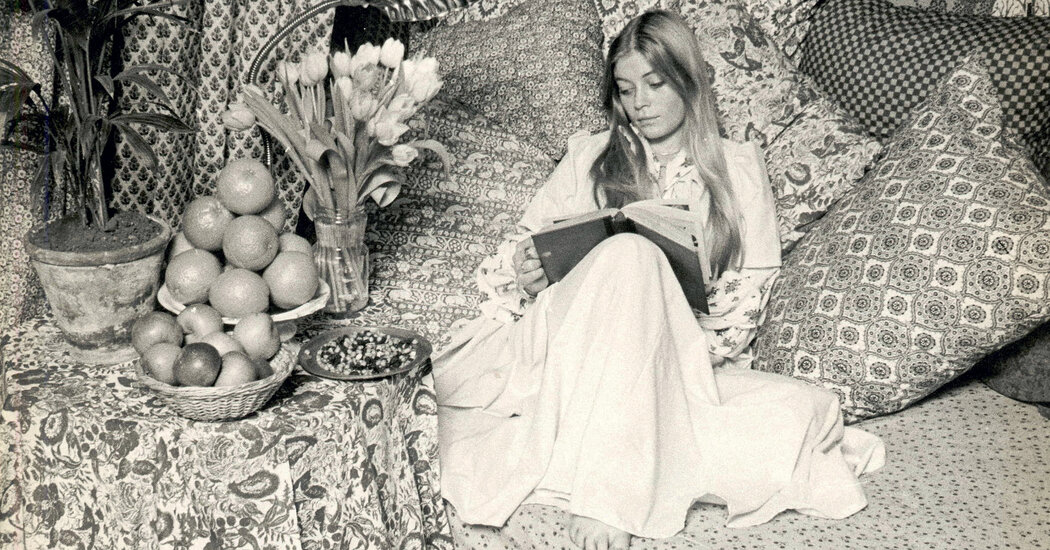

These women’s designs are a reminder that objects of beauty and comfort should be available to everyone, and that these precarious, uncertain times might be making partial pioneers of many of us. The pandemic has caused a wave of city dwellers to light out for less populous locales, and others, quarantined at home, to LARP as frontierswomen in urban kitchens, baking cookies, fiddling with sourdough starters and canning their own food. Still others, weary of technology and its attendant distractions, are heading back to the land, or at least to a patch of it, in search of an alternative to our techno-dystopia. Then, too, we have entered a period of inflation, high gas prices and supply chain disruptions; many are saying it feels like the ’70s — the heyday of the Laura Ashley dress and a decade of dark, anxious undertones — all over again. Who doesn’t want to wrap up in a quilted floral comforter, collapse on the couch and watch “Little House on the Prairie” right about now? It may be this sense, that the world is currently perilous, that’s ultimately driving the popularity of the prairie look: You can wear one of these pragmatic, pretty dresses in your escapist fantasies, but also in your actual life: to a dinner, to a protest, to sit on the floor and play with a toddler. They are also timeless in that they’re unlikely to go out of style by next season — after all, they’ve been in style, more or less, since the mid-1800s.