THERE IS NO dumpling without dough, that universal element of human foodways. Depending on the type and treatment of its ingredients, dough can be silky or flaky, elastic or crumbly, pillowy or crisp. Whatever the texture, a proper dumpling paste is both delicious in its own right and a functional vehicle for filling. For the chef Joe Ng, however, it is something greater. At his restaurant RedFarm, in New York’s West Village, which he opened with the restaurateur Ed Schoenfeld in 2011, Ng has become known for his inventive takes on traditional Cantonese-style dim sum: some modeled to resemble swimming stingrays, others with candy-colored skins and beady black-sesame-seed eyes that mimic Pac-Man ghosts.

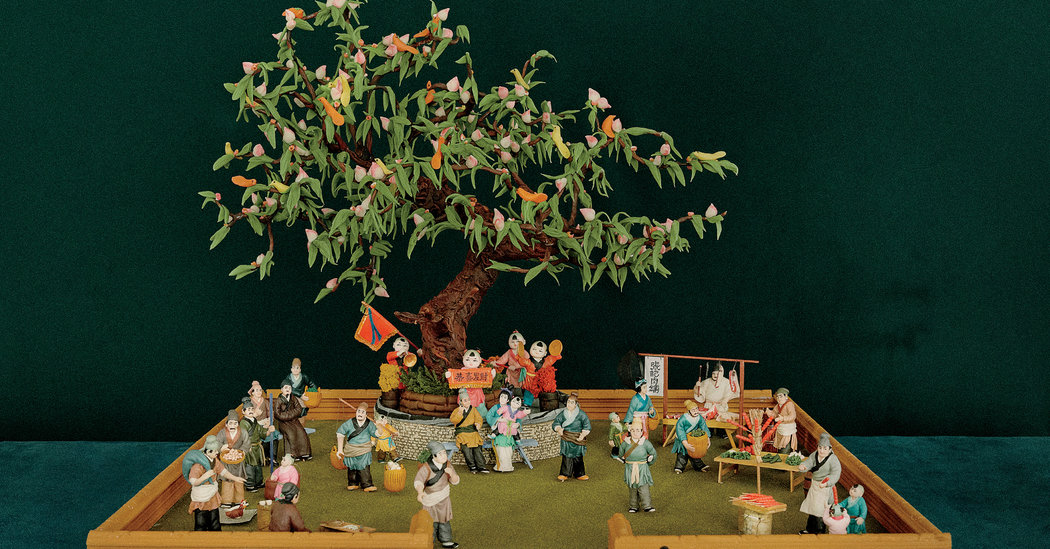

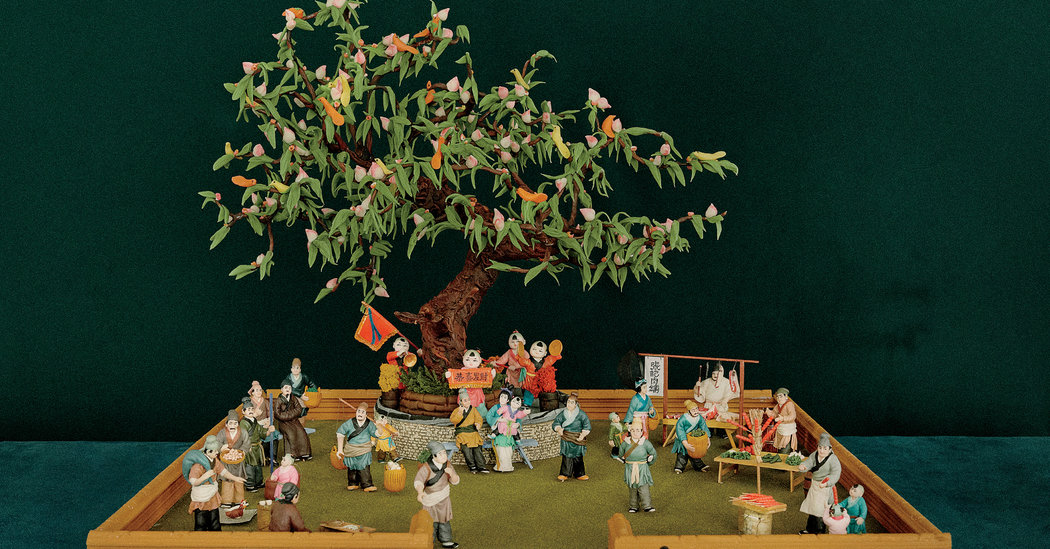

These are foods for the Instagram age, and so the chef has grown accustomed to diners memorializing the contents of every bamboo steamer basket. “The telephone eats first now,” he says with a sigh. But filters and hashtags are not Ng’s primary concern — one senses he is most comfortable creating. And indeed, Ng has found an even more imaginative (if less edible) use for dumpling dough: In his spare time, when he’s away from the sensorium-busting clamor of a commercial kitchen, he sculpts tableaus depicting everyday scenes from traditional Chinese life. There are bustling markets, vibrant fruit trees and children waving flags for Chinese New Year — the scenes are like something from the mind of Pieter Bruegel the Elder if Pieter Bruegel the Elder had lived in Song dynasty China. Every baby and tree branch and bundle of bok choy is made out of a mixture of high-gluten flour, rice flour, water and salt. It is, after all, the material Ng knows best.

[Sign up here for the T List newsletter, a weekly roundup of what T Magazine editors are noticing and coveting now.]

Born in Hong Kong, Ng moved to Park Slope, Brooklyn, with his family when he was 14. Today, he’s considered by his peers one of the best Chinese chefs in the West, and he and Schoenfeld have expanded to London with a new RedFarm that opened in Covent Garden last year (there’s also a location on Manhattan’s Upper West Side). A skilled dim sum chef can fashion a crimped and milky har gow specimen with his eyes closed. Ng quips that he does one better: “I can make dumplings when I’m sleeping.”

Dioramas require the same dexterousness as dumpling making, but also greater attention and patience. After the dough is steamed and sometimes plunged into boiling water to make it softer, it is tinted with artist’s paint and then left overnight to dry and cool. Then Ng begins assembling his figurines, pressing one layer of dough at a time around a toothpick base (each layer must dry for a couple of days before he can apply the next one). “Your hands have a high temperature,” he says. “If you touch the dough too much, it melts.” In the windowless work space of his Staten Island home — filled with about a hundred completed pieces, which keep indefinitely if left in dry conditions and away from sunlight — a fan blows cool air at the works in progress. More elaborate structures, like the peach tree pictured at the top, begin with a wire base. Ng also allows himself nondough extras, like a swatch of faux grass purchased at a model-railroad shop in New Jersey or a tiny bench made from wood bought at Home Depot. A scene can take weeks of labor, and as with many efforts that demand solitary focus, the task lends itself to contemplative moods. “When I’m very depressed, I start making the dough,” says Ng, who works on his sculpting in obsessive bursts, sometimes going two days without sleep.

SCULPTING DOUGH FIGURINES is a dwindling folk art in China, one that is said to date back at least 2,000 years. What likely began as an offering to gods or ancestors broadened into a range of applications; dough figurines became toys for children, collectibles, banquet showpieces and a popular feature of festivals. The practice belongs to a global history of crafts that turn pastry supplies into raw materials: Artists known as sukker nakkasarli built decorative sugar bestiaries in 16th-century Constantinople; 18th-century France was awash in manuals detailing pastry techniques, such as shaping flowers from pastillage; and when Henry III of France visited Venice in 1574, he sat down to a lavish banquet where the plates, knives and linens were all fashioned from spun sugar. In 1999 in Lübeck, Germany, a marzipan museum was installed above Café Niederegger; it features a “Last Supper”-style display of figures sculpted from 1,100 pounds of almond paste. What the above disciplines have in common are finicky materials, a lengthy process and an excruciatingly niche market (these days, sometimes no market at all) for the end results.

It’s no wonder, then, that “it’s hard to find people who do this,” as Ng says. “If you sold a dragon for $300, and it takes you a week to make it, how are you going to survive? It’s a hobby. For fun.” For fun, yes, if your definition of fun involves hours of historical research, days of dough-drying and the pursuit of an esoteric craft that is as unremunerative as it is beautiful. Easy to learn, tough to master.