ONCE, HERBS WERE weapons. Five thousand years ago, the Sumerians recorded, in cuneiform, lifesaving prescriptions of myrtle and thyme. The oldest surviving text of Chinese herbal pharmacology, extolling the benefits of ginseng, camphor and cannabis, was set down in the first century A.D. Around the same time, the Greek physician Dioscorides documented the properties of herbs he encountered as a surgeon with Nero’s imperial Roman army; Western doctors consulted his compendium, “De Materia Medica,” for the next 1,500 years. In Renaissance England, chamomile, hyssop, pennyroyal and tansy were strewn on floors to ward off the plague; men and women wielded prophylactic posies of flowers and herbs like swords.

But with the triumphs of science and technology in the 19th century, herbs receded in significance. “These ancestral leaves, these immemorial attendants of man, these servants of his magic and healers of his pain,” as the American naturalist Henry Beston described them in 1935, became workhorses, steadfast and drained of alchemy. They came to be defined by that most prosaic of qualities: usefulness. Even in the kitchen, they were underlings, essential but largely confined to a supporting role. Any prettiness they possessed was incidental to their practical purpose and noted only in passing, en route to the boiling pot.

As the modern world has lost its luster, however, herbs are coming into ascendance once more, reasserting their curative powers and claiming a beauty of their own. A private herb garden has become a status symbol, as chefs flaunt seasonings that have fallen out of favor or are hard to find, like salad burnet, its bite as cleansing as a cucumber’s, or sculpit, which evokes a bashful tarragon. This goes beyond the now mainstream farm-to-table movement, which has roots in the counterculture of the 1960s, to what the Spanish chef Rodrigo de la Calle christened gastrobotánica: the restoration of forgotten plants to the realm of cooking. The British horticulturalist Jekka McVicar, who grows more than 650 varieties of herbs on her farm in South Gloucestershire, England, has been approached by British chefs seeking sweet woodruff, beloved in Germany as an infuser of Jell-O and beer, and baldmoney from the Scottish highlands, its flavor a sidestep from cumin. Farm.One, an underground hydroponic facility in downtown Manhattan, supplies avant-garde restaurants and pizzerias with rarities such as tiny, bright pluto basil and akatade, a Japanese water pepper that imparts a faintly anesthetic heat.

Even more standard herbs are having a heyday. The Israeli-born chef Yotam Ottolenghi, of Nopi and the Ottolenghi delis in London, deep-fries sage to intensify its flavor, then sprinkles it on dishes for a staccato of crunch — or turns whole leaves of basil and chervil into tempura, to be dipped in vinegar. At Cicatriz in Mexico City, the American-born Scarlett Lindeman steeps fresh bay leaves — “slick and oily,” she says, unlike brittle, dried leaves that don’t “taste or smell like anything” — in a beef braise called estofado and heaps plates with a mezcla madre, a “mother mix” of cilantro, mint, parsley and basil, meant to be worked into each dish.

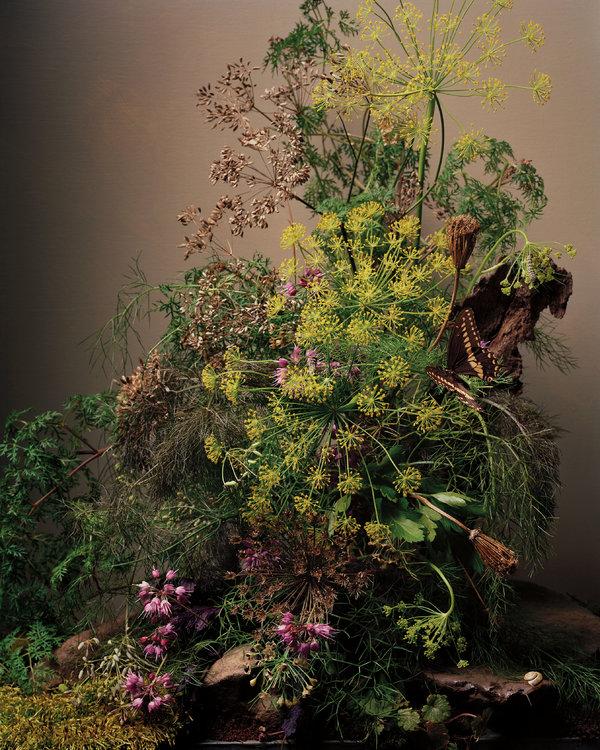

From left: an explosion of fennel seed heads, bronze fennel fronds, giant fennel, Italian and milk parsley, allium, garlic chives, mizuna, black swallowtail chrysalides and caterpillars, a swallowtail butterfly — plus your standard garden snail. Both arrangements in this story were created by the floral artist Joshua Werber.CreditPhotograph by Sharon Core. Styled by Joshua Werber

FLORISTS HAVE STARTED coming to McVicar’s farm, too, seeking inspiration. Now the likes of feathery bronze fennel, once eaten by Roman warriors before heading into battle; dill with its whispery fronds; pink, fuzzy-hearted, flu-fighting echinacea; and wild garlic, whose white-hooded flowers call to mind novice nuns, come entwined with conventional blossoms or command entire bouquets. The effect is often nostalgic, a paean to some lost pastoral idyll, but also intensely of the moment. “We’re in turbulent times,” McVicar says. She sees the embrace of herbs as a yearning for connection with not simply the natural world but our analog past: “We want to remember who we are, where we’re from, how to be gentle with ourselves.”

Herbs are botanically delineated as among those plants that bloom and then die down to the ground, with only roots to attest to their persistence. (Rosemary and sage are among the notable exceptions.) They have a kinship to wildflowers, which have proliferated in floral designs in recent years, in keeping with a turn toward foraging and unstructured, almost anarchic arrangements. But unlike wildflowers, whose allure is their existence outside of human conscription, herbs have always had a relationship with mankind, from before we even recognized ourselves as mankind: feeding, protecting and arguably improving us. Parents come to McVicar’s herb farm in search of bouquets to ease their children’s asthma. For Mother’s Day, Terri Chandler and Katie Smyth of Worm in London tuck lavender and rosemary into bouquets and deliver them with cheesecloth and string, to give the herbs a second life as a bath soak.

To Ellie Jauncey and Anna Day of the Flower Appreciation Society in London, herbs are the equals of flowers and ought to be treated as such. Their arrangements, mostly of locally grown plants, are built to ramble, inspired by the spirit of the great British country gardens at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent and Great Dixter in East Sussex. “I see no point in segregating plants of differing habit or habits,” wrote Christopher Lloyd, the gardening writer and master of Great Dixter until his death in 2006. “They can all help one another.” It’s an ethos shared by Amanda Luu and Ivanka Matsuba of Studio Mondine in San Francisco: What grows together, goes together. They like to mix chives with roses, a pairing commonly found in gardens. The alliums’ pungency repels aphids and larger threats (compounds in the leaves offer a kind of herd immunity against black spot, a fungal infection and botanical equivalent of the plague). Herbs are good for pollination, too: Bees are drawn to flowering herbs more than to flowers themselves, with the herbs’ healing powers suffusing the nectar.

Part of the appeal of herbs is how quotidian they are, which makes them startling out of context. Luu and Matsuba transform yarrow, with its densely packed white corymbs, or dried oregano — stems faded to a faint taupe while the tips still give off a purple pulse — into near abstractions of color and silhouette. For the New York-based florist Lewis Miller, texture is the draw: “It makes you want to touch and pinch the leaves,” he says, which in turn releases their aromatic oils.

With that steadying scent comes recognition — we know these plants — and a sense of continuing. These ideas are central to the work of the married florist-farmers Mandy and Steve O’Shea, of 3 Porch Farm and Moonflower Design near Athens, Ga., who grow and harvest their own herbs and flowers using solar power and biofuel, rooting each bouquet in season and place. Of late, Mandy has found that couples will request herbs in their wedding arrangements because they cook together. “They’ll be reminded of their celebration every time they chop those herbs in the kitchen,” she says.

But do herbs last as long as flowers? “I don’t think it matters,” McVicar says. Endurance can be artifice; if something is fleeting, at least it’s real. Should you want your bouquet to eke out another day, however, McVicar suggests a dash of fizzy lemon soda in the water. It’s an old-fashioned remedy that those who till gardens have known for years, and it works.