To celebrate Modern Love’s 15th anniversary this month, we’re publishing a series of special features — three classic essays from the column’s early years and four conversations with writers whose stories were adapted for the television series that began streaming on Amazon Prime Video on Oct. 18.

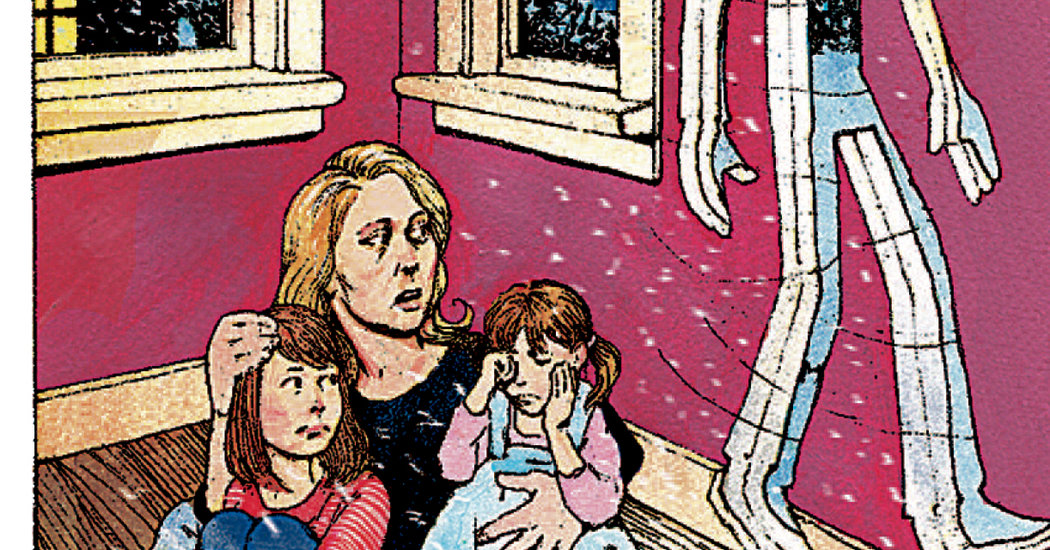

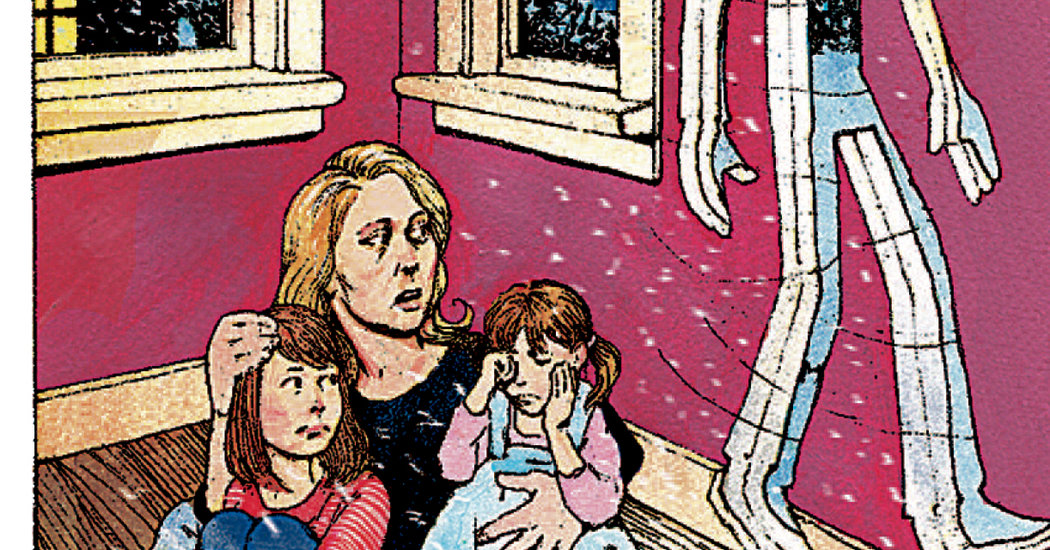

This week we present the third Modern Love essay ever published, Theo Pauline Nestor’s bracing account of divorce, which swamped our inboxes with email, our first glimpse of the column’s potential emotional impact. (The daughters referenced in the essay are now 25 and 21; you’ll find a fuller update from the writer below.)

Some marriages grind slowly to a halt. Others, like mine, explode mid-flight, a space shuttle torn asunder in the clear blue sky as the stunned crowd watches in disbelief. And the hazardous debris from the catastrophe just keeps raining down.

It was late September, still warm but past the last hot stretch of Indian summer. I had waited for a day cool enough to roast a chicken for my husband and two young daughters. When I put the five-pound chicken in the oven, a shower of fresh green herbs clinging to its breast, our marriage was still intact. By the time I pulled it out, my husband had left our house and driven away for good, his car stuffed with clothes slipping off their hangers.

It was my call to the bank to check our balance that caused the fatal blowup. Although my husband’s destructive compulsions with money had threatened our marriage before, I believed those days were long behind us. But that afternoon, without even trying to, I discovered the truth: Far from changing his ways, he had simply become more secretive. I confronted him. And that, as they say, was that.

[Sign up for Love Letter, our weekly email, and read and listen to all things Modern Love here.]

So the roast chicken fed only one person that night: our 9-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. I couldn’t eat, and our 5-year-old, Grace, announced she wouldn’t eat a real chicken, only chicken nuggets. I took the red box from the freezer, plucked out five tawny squares, heated them in the microwave and placed them in front of Grace, who believed, as did her sister, that their father had gone downtown to meet a friend and that he and this friend were going on an impromptu car trip. “Dad will come home in a week,” I told them. I didn’t know what else to say.

I thought of my childhood friend Nancy, whose marriage had fallen apart a year earlier. I have three friends from childhood I am still close to; coincidentally, all four of us married around our 30th birthdays. For 10 years we beat the odds. Then Nancy’s marriage broke up, and now, with mine, our little group reflected that often-cited statistic: half of all marriages end in divorce.

At Nancy’s wedding, the minister had briefly turned his attention from the newlyweds to address the group directly. “It is up to the community to hold a couple together,” he had said in his commanding voice. “Each of you here is responsible for remembering for this couple the love that brought them together and the commitment they’ve made.”

I took his words to heart, silently vowing to support Nancy and Terry, to remind Nancy of Terry’s strengths some day when she might vent to me after a marital spat. Despite their vows and my support, despite 10 years and two sons, their marriage couldn’t be held together. And now, despite 11 years and two daughters, neither could mine.

The women I grew up with, like most women today, have tangible, marketable skills. One is an electrician, another a graphic artist, a third a nurse. Inside or outside a marriage, they can support themselves. I, too, am a well-educated woman with a decent work history who actually made more money than my husband when we married. I prided myself on being self-sufficient. But we both wanted someone to be home with the kids and we decided it would be me, so I stopped working and let him support us. And now I’ve ended up in the same vulnerable position I once thought was the fate only of women who married straight out of high school, with no job experience beyond summer gigs at the Dairy Queen.

Not that I would have done it differently. I have valued my time with our daughters more than any other experience I’ve had. But for a stay-at-home mom like me, divorce isn’t just divorce. It’s more like divorce plus being fired from a job, because you can no longer afford to keep your job at home, the one you gave up your career for.

When I worked as an English professor at the community college, we called people like me displaced homemakers. I can now imagine legions of gingham-aproned Betty Crockers spinning perpetually, forever tracing their feather dusters across imaginary furniture, never ceasing to “make” the “home” that is no longer there.

Now that my income has dwindled to child support and a meager “maintenance” check, I must leave this job and get a “real” one. I add up our expenses for a month and then subtract his contribution. The remaining total indicates that to keep the girls and myself out of debt, I will need to net a third more than the most I’ve ever made.

And divorce is its own job, with its course of study, its manuals. One of the many divorce books heaped on the floor beside my bed urges me to develop two stories about the breakup: a private one and a public one. I’m told that I should practice a few sentences that I can recite (in the grocery store, on the playground) without excessive emotion, a sort of campaign slogan for my divorce. And it does seem as if much of my daily work involves negotiating the snowy pass between my private and public self.

Alone, I shriek into my pillow, and I shout “Bonehead” through the closed car window as I drive past my ex’s new apartment. In public, I am stoic, detached, nodding philosophically as a married mother from Elizabeth’s soccer team tells me: “Your grief is like a house. One day you’ll be in the room of sorrow and the next you might be in anger.”

A humbled divorcée, I can only act as if all this is news to me.

“And oh, denial!” she adds. “That’s a room, too — don’t forget.”

Eventually you have to tell everyone who hasn’t heard through the grapevine. Some people get “the whole story” and some just get the abridged “we’ve separated” version.

The whole-story people are exhausting. At first it’s all relief and adrenaline as you recount the moment you realized the shuttle was breaking apart. But then you are overwhelmed with dread as you come to understand how many whole-story people there are in your life. Still ahead are countless oh-my-gods and I’m-so-sorrys and you-must-be-kiddings. You hear sympathetic and understandable questions coming at you, and your tongue grows thick and unfamiliar forming all those words one more time. You consider a form letter:

Dear Good Friend Who Deserves the Whole Story

I’m sorry this is coming to you as a form letter.

I’m sorry about a lot.

I’m just sorry.

Or perhaps there could be a website: www.whatthehellhappened.com complete with a FAQ link.

Q. What about the children?

A. They live with me but will stay with him every Friday and every first, third and fifth Thursday night as well as the first Saturday of every month. Yes, it’s hard to remember which week it is.

Q. Will reconciliation be possible?

A. No. If you read the whole story you will understand why. (Use password to access the secure site.)

Q. Are you O.K.?

A. No, I’m not. Thanks for asking.

Q. Is there anything we can do to help?

A. Yes. Click on the Send Money link below.

When I took off my wedding rings, my finger had atrophied underneath in a manner that seems excessively symbolic. I protect this white band with my thumb like a wound. I look at other women’s ring fingers: gold bands, simple solitaires, swirling clusters of diamonds. The fact that they’ve managed to keep those rings in place seems miraculous, a defiance of gravity.

When I wore my rings, I was a different person, emboldened in the way one can be in a Halloween costume. I could laugh as loudly as I wanted and go out with dirty hair and sweatpants. I was married. Someone loved me and it showed. I could refer to a husband in conversations with a new friend or a store clerk. They didn’t care if I was married or not, but I did. My ring said: You can’t touch me. It’s like base in a game of tag. You’re safe.

Now, when I go to bed I turn the electric blanket to high and let the heat soak into my skin. Sometimes, lying here, I think of this divorce business as something like flu. The feverish beginnings, as miserable and sweaty as they are, are somehow easier to get through (they are a blur, really) than the many half-well, half-sick days that follow, days when you’re not sure what to do. You’re too well to lie in bed watching TV but too sick to go out and do all the things well people are expected to do.

To fall asleep, I resort to the old routine of counting my blessings. I count my daughters over and over again. I count their health, their happiness, the gift of who they are.

I urge myself to find something else I am grateful for but can’t. And then I realize there is something.

It’s this rawness of spirit, the way the crust of my middle-age shell has been blown off me, and here I am, the real me. I am no longer the person who can pretend everything’s O.K. I can no longer think of myself as “safe” or protected. I know now it is up to me to hunt, to gather and to keep shelter warm.

Theo Pauline Nestor is the author of “How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed: A Memoir of Starting Over” and “Writing Is My Drink: A Writer’s Story of Finding her Voice (and a Guide to How You Can Too).”

Update from the writer:

“Reading this essay now, I recall how very afraid I was for the first few years after my divorce. Although I wasn’t sure what ‘not making it’ might look like, I would often ask myself if we were going to make it. We did make it. My daughters are now grown (21 and 25) — thriving and pursuing their dreams. When I was writing ‘How to Sleep Alone in a King-Size Bed,’ I felt like I needed to remarry in order for the reader to have a happy ending. But life did not supply that ending. I was in a few relationships in the decade after my divorce, but none of them evolved into cohabitation or marriage. And as my daughters left the nest, I realized how very much I was going to dig life in my solo nest. And I do! I moved out to a community a ferry’s ride from Seattle a few years ago and am loving it.”

Modern Love can be reached at modernlove@nytimes.com.

Want more? Learn more about the Modern Love TV series, now on Amazon Prime Video; sign up for Love Letter, our weekly email; read past Modern Love columns and Tiny Love Stories; listen to the Modern Love Podcast on iTunes, Spotify or Google Play Music; check out the updated anthology “Modern Love: True Stories of Love, Loss, and Redemption”; and follow Modern Love on Facebook.