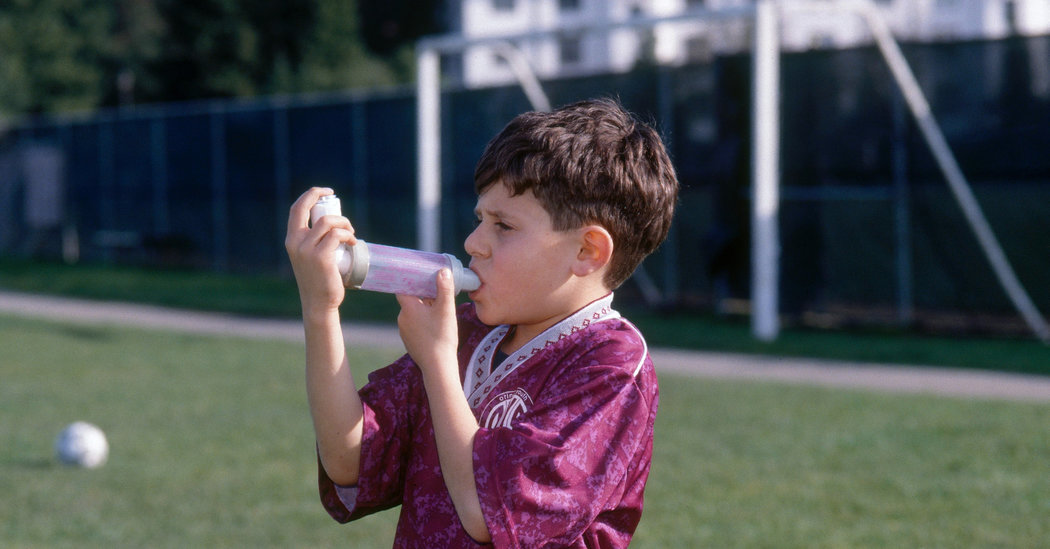

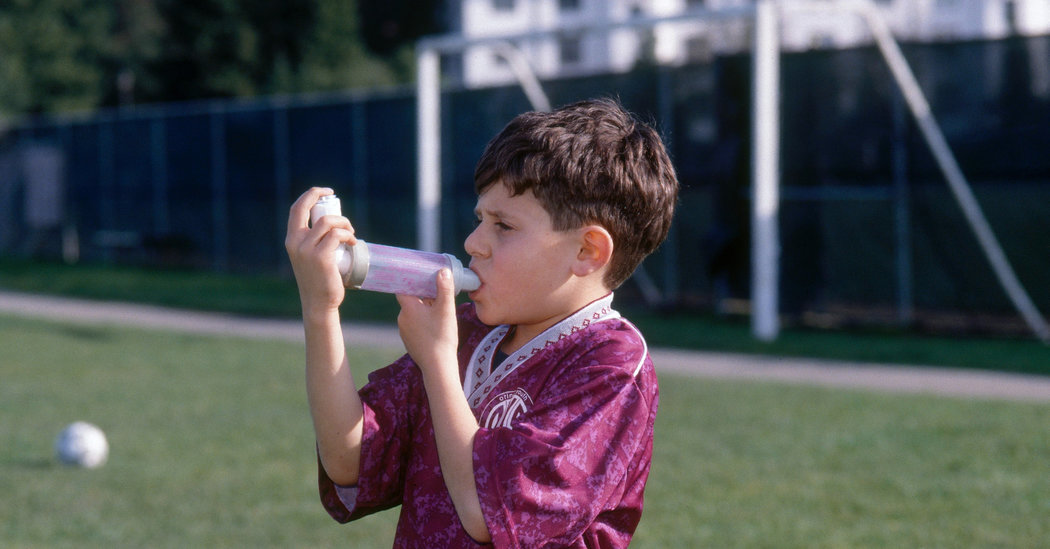

Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood, and using an asthma inhaler is often a first step toward medical autonomy for a child with asthma. But the value of technology depends on how you use it, and children — and adults — need to use their inhalers correctly for the devices to help.

The smooth muscle that lines the small airways in the lungs is too ready to react in asthma, squeezing down and narrowing the airways in response to a whole range of triggers in different people, from infection to dust to cold air to exercise.

Inhalers are used to deliver two different kinds of routine asthma medications, with the idea being that the drugs will go right to the airways, where they act. Once or twice a day, children may take what are called controller therapies, most often inhaled corticosteroids which decrease chronic inflammation in the lungs and make exacerbations less likely. And then, when they feel symptoms coming on, or find themselves in a situation where symptoms seem likely, they use what are called rescue medications, bronchodilators which relax the smooth muscle so that air can move through those tubes.

A study published in February in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology suggests that many patients — adults and children alike — are not using their inhalers correctly, and may not be deriving the full benefits of the drugs.

Dr. William C. Anderson III, the first author on the study and co-director of the multidisciplinary asthma clinic at the Children’s Hospital Colorado, said that there are at least seven steps in using an inhaler correctly: You have to take off the cap, shake the inhaler for three to five seconds and connect it to the spacer (a chamber between the inhaler and the patient’s mouth that holds the drug suspended and makes it easier to breathe it in). Then you are supposed to exhale completely, and put the mouthpiece or mask in or around your mouth correctly, forming a tight seal. Then you release the medication from the inhaler by pressing the canister down, breathe in slowly and deeply through the spacer (for spacers with a whistle, you do not want to hear the whistle), and hold your breath for 10 seconds. Finally, you exhale again — and then you wait a minute and repeat the process.

If the second puff comes too quickly after the first, the steps are not being followed correctly. In the new study, researchers used electronic medication monitors on the inhalers which recorded the time interval between the first puff and the second puff. This essentially let them follow 7,558 patients into the home to see how the devices were used.

Eighty-four percent of the patients did not wait the 30 seconds that the researchers felt was the absolute minimum time between inhalations. More than 50 percent waited less than 15 seconds.

“We were shocked in terms of the patterns of medication administration that appear to be contrary to how we teach that medications should be administered,” said Dr. Stanley Szefler, the director of the pediatric asthma research program at Children’s Hospital Colorado, who was a co-author on the study.

“This study shows that our patients are not taking the medications in the way they ideally should be,” Dr. Anderson said. “That also falls to us, as providers, to make sure they know all the steps in taking an inhaled medication for asthma.” Even doctors don’t necessarily know all the steps, he said, and need to be educated before they can, in turn, educate their patients.

Dr. Francine M. Ducharme, a professor of pediatrics and social and preventive medicine at the University of Montreal, has studied the efficacy and safety of asthma management. When a treatment of known efficacy doesn’t work for a child, she said, the four major reasons are inadequate technique, suboptimal adherence to the regimen, other coexisting medical issues, or environmental triggers (for example, maybe the child is profoundly allergic to the cat).

Problems with technique and adherence are the main ones. It’s not enough to observe the child once, she said. “We need to recheck the technique, children are very creative.” Often, they use the correct technique the first time through, then find ways of getting around it. “Whenever a medication doesn’t work or have efficacy, before you think about stepping up medications, you need to review those four criteria.”

Everyone, adult or child, should use a spacer, she said, to make sure the drug is properly inhaled into the lungs rather than deposited in the mouth. In a 2018 study of what convinces parents to adhere to inhaled corticosteroid regimens with their asthmatic children, a large proportion of parents said that children 8 and over were partially responsible for using their inhalers and noticing whether they were empty. But proper inhaler technique needs to be taught to parents, she said, and they need to understand that they have an important ongoing role.

In their clinic, an asthma educator works with families, Dr. Ducharme said, and “it’s amazing the number of times we find things that have to be corrected.”

Parents may believe their children have mastered the technique and learned all the steps, Dr. Anderson said, but “we need the parents to be there to observe them and make sure they’re taking it correctly,” especially for children under 12. In fact, among the patients in the study, he said, although there was “across the board poor inhaler technique,” the group with the best technique was the 4- to 11-year-olds; the researchers can’t say why, but their working theory is parental supervision. The worst technique was in the 18- to 29-year-olds.

One risk of poor inhaler technique is that children’s asthma will be more severe, and they will miss out on the opportunity to play or participate in sports, or perhaps even will need trips to the emergency room. They may feel frustrated because they’ve been trying to take care of themselves by using their inhalers, and it just doesn’t seem to be helping. But another risk is that because they seem not to be responding to the medications they are taking (because the medications are not being delivered to their lungs in the right doses), their doctors may prescribe stronger and more expensive medications, or more complex regimens.

“If a kid’s asthma is not well controlled, I would want to be sure if I’m the doctor I’m addressing technique first and foremost before escalating the medications,” Dr. Anderson said. “If you notice things are not well controlled with your child’s asthma, the first thing to check is whether the child is taking it appropriately at the correct times.”

The most important message, Dr. Szefler said, is “we have very effective medications available, and the majority of asthma can be well controlled.” But controlling it involves successful communication and teaching, and a full collaboration with patients and parents. The goal, he said, is to “get the most out of the medications to control the disease and prevent adverse outcomes in childhood and later life.”