The Catskills have had more comebacks than Tony Bennett.

The first wave came in the late 1880s when summer vacationers filled boarding houses. Decades later, Jewish families arrived by train to play shuffleboard and swim in opulent hotels. Remember Woodstock in the 1960s? That’s when the hippies showed up. Nowadays, aging Brooklyn hipsters are bringing their Urban Outfitters aesthetic to Kerhonkson and Fallsburg.

But while much has been made of the mountainous area northwest of New York City, its most recent rebirth as a summer escape (Hamptons, anyone?) is as much a story of resilience as it is one of reinvention. “People keep trying to impose different things on this swath of land,” said Victoria Wilson, a senior editor with Knopf publishing who bought a home in Sullivan County 30 years ago. “It is different, but it remains the same. It exudes something that is a little mysterious.”

Phase one: The Victorian era

The Times has chronicled the changing culture of the Catskills, long a home to artists and the independent-minded. Dutch immigrants settled there in the 1600s where they grew wheat and rye, making way for dairy and egg farming later on.

A new group of artists and writers would arrive in the 1800s. The artist Thomas Cole settled there in 1825 after emigrating from Lancashire, England, seven years earlier, bringing a number of others with him. A painter and engraver, Cole became a founder of the Hudson River School, one of the country’s first great American art movements.

Celebrated artists like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt were enamored with the area’s stately peaks and valleys. They painted gauzy landscapes where fishermen plucked plump brook trout from Esopus Creek. The Catskills became notable, particularly among patrons who commissioned paintings to be hung in European salons and the drawing rooms of wealthy New Yorkers.

By the mid-1800s, farmers and innkeepers began renting out bungalows to boarders from the city looking to escape the summer stew of humidity and heat.

“There is a delicious sense of remoteness; a feeling of the completeness of nature’s most bountiful gifts of expression,” The Times wrote in 1872. Visitors, it explained, “will find here no modern hotel luxuries; no bells to ring; no waiters to conciliate; no baths to take unless they might fancy a plunge into the rushing foaming mountain stream that is calling all day from the twilight gorge.”

Tourists arrived mostly by train. The trek could take as much as a day from Manhattan, which meant middle-class families who ventured there often stayed a week or more, especially during the summer. The mountains were a haven for painters. Women wore blue flannel dresses and waterproof cloaks — as opposed to the frippery of Madison Square Park — and climbed steep gorges with sketchbooks, paintbrushes and pencils in hand.

Artists painted out of doors; the romanticism of nature was meant to evoke a feeling of otherworldliness and the sublime. They too wanted to capture what was left of New York’s verdant forests after logging stripped the trees for use in housing and railroads, and tanneries cleared the land of eastern hemlock, whose bark was used for tanning.

In 1896, a physician, Alfred Lebbeus Loomis, founded a sanitarium in Liberty, N.Y., for tuberculosis patients who believed that the cure for the disease was fresh air and rest. Though Loomis died before the sanitarium was christened, its opening would have a chilling effect on summer travelers who were wary of making their way north with sick fellow passengers.

As a result, the local economy stalled.

“They were coughing and hacking on the train,” said Stephen Silverman, the author of 2015’s “The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America,” of the sanitarium’s patients. “The boarding houses were filled with consumptive patients. People could not sell summer homes. Real estate plummeted. The Catskills quickly went out of favor.”

Phase two: The Borscht Belt

Decades passed. And, eventually, the Catskills, which comprise Delaware, Greene, Schoharie, Sullivan and Ulster counties, were ready for a revival.

In came the era of big hotels. Jewish proprietors set up self-contained hospitality fortresses in the 1920s, which later gave Jewish families a place to summer when they were discriminated against elsewhere. The most prominent of these was Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, a kosher establishment that started as a farmhouse in Liberty in 1919. Jennie Grossinger, the formidable daughter of the founder, oversaw its dominance as a major hotel that had its own airstrip and post office.

“It was the model for hospitality,” Mr. Silverman said. “You didn’t need to leave the front gate. She created a kingdom. If you needed gas for your car, you got it there. You needed a ball gown, you could find one.”

Marisa Scheinfeld, the author of “The Borscht Belt: Revisiting the Remains of America’s Jewish Vacationland,” used to visit the Concord Resort Hotel as a young girl. “‘Dirty Dancing’ is the cliché,” she said, referring to the 1987 romantic comedy starring Jennifer Grey as a teenager who falls in love with a hotel dance instructor while vacationing with her parents in 1963. (Grossinger’s was the inspiration for the film’s fictional Kellerman’s resort.) Some families moved up for the summer; others saw a two-week stay as a substitute for a trip abroad.

“You got menus for the day in the morning; the night life was bustling,” Ms. Scheinfeld said. “There were meals, swimming, fox trot lessons. My grandpa was a card shark. He used to go play. I’d go with my grandma to the steam room. I remember a lot of bingo and swimming.”

Jewish musicians and comedians, too, became celebrities in the Catskills long before they achieved mainstream success. Among them: Woody Allen, Jerry Seinfeld, Sid Caesar, Joan Rivers and Jackie Mason. The comedian Jerry Lewis worked as a pool boy and busboy while his parents performed a vaudeville act. “It was here they honed their humor,” Ms. Scheinfeld said.

Much has been made of the era in movies and television shows. The second season of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” a comedy about a Jewish housewife in 1958 who wants to be a comic in New York, features several episodes set in the Catskills. At the same time, the Catskills were on the verge of another economic downturn as the Borscht Belt lost its cachet. By the mid-1960s, Ms. Scheinfeld said, “The Catskills felt stale.”

Phase three: The hippies and beyond

The Catskills fell out of vogue for a combination of reasons, Mr. Silverman said. More women entered the work force, airfare became cheaper and families moved to bigger homes in the suburbs. Air-conditioning was also widely available, which meant New York City denizens didn’t have to escape the city to keep cool. And after the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, Jews, like black people, could no longer be discriminated against, and thus had more places to go.

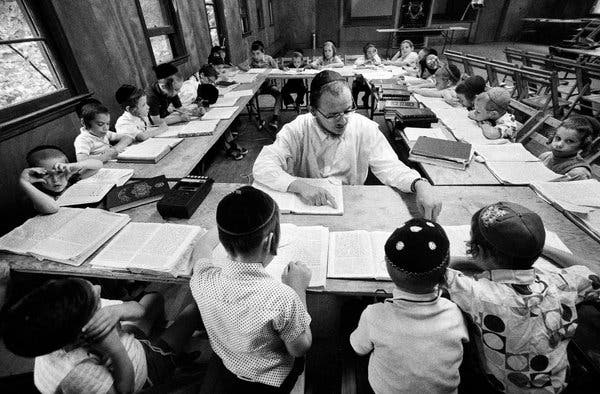

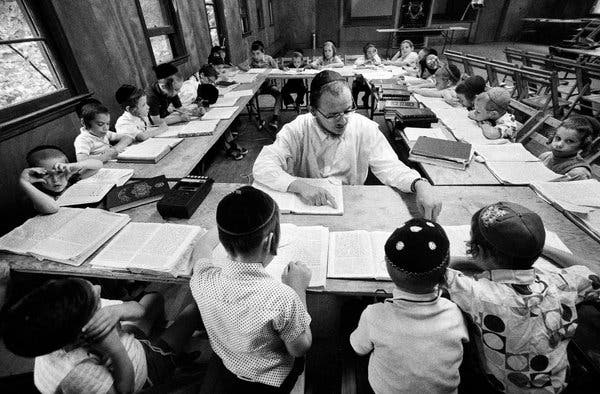

CreditJack Manning/The New York Times

By the late 1960s, Jewish enclaves in the Catskills had given way to an influx of hippies who were attracted to the cheap land and free-spirited lifestyle. “You could always do whatever you wanted there,” Mr. Silverman said. The influx culminated in the Woodstock festival in August 1969, when half a million people convened on a dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y., for a three-day music extravaganza to celebrate hippie counterculture and protest the Vietnam War. Once there, the dissenters formed communes and art communities.

“There still are a lot of hippies who are 1,000 years old,” Ms. Wilson said.

The area languished again in the 1980s and 1990s. But it still had its charms, and it attracted a hearty, entrepreneurial crowd. Celebrities, including the actors Debra Winger and Mark Ruffalo, have homes there. In recent years, visitors from New York City have set up cafes, bars, woodworking shops, art studios, breweries and writing residencies that many hope will bolster a local economy that is still reeling from the last recession in 2008. Of course, it no longer takes a day to reach the Catskills by train, making it an easy weekend sojourn.

“It is ripe for a revival,” Mr. Silverman said.

Ms. Wilson, though, struck a note of caution. Like other parts of New York, a socioeconomic divide remains between the people who live and work there and those with stately homes who visit only on weekends. “It is still very poor,” she said. And there are questions about how best to grow. There was a recent debate about whether to allow fracking. Others are hoping a new casino will bolster the area’s fortunes.

“There is a duality,” Ms. Wilson said. “And I wouldn’t want to be any place else.”