Bill Mullen, a fashion stylist and illustrator, wants you to know that he used to wear a belt made out of teeth, skulls on every finger and cataracts of crosses, his exotic turnout once spurring a stranger to bellow, “Go for it, space monkey, go for it.”

Solange Knowles is touting “Metatronia,” an architecturally inspired performance piece conceived to explore the relationship of movement and architecture. “It’s been a dream,” she confides, “to build modular sculptures that can tour, interact, and engage with the public.”

And Caroline Calloway, a writer and eyebrow-raising social-media diva, is happy to share what may be more than you ever wanted to know about her relationship with her father: “Scary,” she confides, “to see a parent living in a home full of dirt and trash and hoarded things.”

Famous or possibly hoping to be, they are members of a chorus, voices resonating in supersize captions, some as long as 300 words, published not on Facebook or Tumblr, as you may suspect, but on their Instagram feeds.

Champions of the long-form post, they are confounding expectations.

Instagram, after all, was conceived as a photography app, a place to post the contents of a fancy meal, catch the play of light on a tousled bed, celebrate a professional coup, show off a bikini body or a family trip to the beach.

It’s flourishing now as one of the web’s most compelling storytelling platforms, a repository for uplifting confessions, compressed screeds, some with candidly political overtones, self-help digests, mini essays and speculative musings and, perhaps most compellingly, serialized memoirs in sound-bite form.

No question, the long-form caption is trending, said Marcus Messner, an associate director of the Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture at Virginia Commonwealth University. It’s being exploited as a bid for attention, a quest for connection and, not incidentally, Dr. Messner noted, as a way to foster the kind of visceral engagement that photos alone cannot hope to command.

Megacaptions, which first became popular a couple of years ago, have prompted more than one observer to anoint them as a modish alternative to blogging. “Lately, I’ve started to wonder if Instagram is the new WordPress,” Harling Ross, an editor at Man Repeller, wrote at the time.

It may or may not be all that. But as a catchall for the sorts of brief, often emotionally charged narratives that used to proliferate on personal blogs, the wordy caption is clearly gaining traction.

“People write long captions to document big moments in their lives that are both positive and challenging,” said Robby Stein, the director of product for Instagram. Last year, to encourage and facilitate those stream-of-consciousness ramblings, Instagram introduced Type Mode, a facsimile of an old typewriter font, to be used on Instagram Stories, the Snapchat-like feature where people post texts, photos and videos, which then disappear after 24 hours.

Using such features can be cathartic and can generate suspense. “You relate to the person posting a photo and text from a hospital bed,” Dr. Messner said. “You can’t wait to see what comes next.”

In recent months, Lena Dunham, that consummate mistress of the let-it-all-hang-out narrative, chronicled the psychic and physical fallout from a series of surgeries. Intending to inspire, she posted a solemn missive alongside a selfie that showed her in pajamas, making Sculpey beads at her dining table.

“Some of us need to heal because we are scared, because people we love and people we identify with and people we could very well be are under attack,” she posted. “It is a fog that doesn’t really lift.”

Her own mists appear to be clearing: Next to her portrait she told her fans, “Here I am healing my mind & hands.”

Mr. Mullen, lyrically and often movingly, chronicles the triumphs and trials of coming of age in New York in the early 1980s. “I used to envision the city as a fantasy of hope, but now the place that was going to save me was scaring me,” he wrote in a post commemorating World Aids Day. “I remember thinking that God was giving me a warning.”

It’s more than visual froth

With plenty of outlets for verbal self-expression, why write at length on Instagram?

Well, there is, for starters, the platform’s enormous popularity. And for users, there have been fewer hurdles to clear. “In early days of Facebook, you had to be friends with other people on Facebook, you had to be invited,” Mr. Stein said. “Instagram has always had a completely public profile. It was easier to share.”

Supersize captions are often most riveting as an expression of so-called realness, lending heft and credibility and to a medium long sniffed at as visual froth.

“Ultimately, users are deeper than the glossy or like-for-like images that pervade their feeds,” said Clare Acheson, a branding strategist with Trout Creative Thinking, an advertising agency in Melbourne, Australia.

“An image may first spark their curiosity, and then they seek to discover context,” Ms. Acheson said, “whether that be a news-based narrative, op-ed commentary or a personal account of an experience that tells a fuller story and explains the ‘why’ behind the image.”

Long captions can be purely descriptive. On @ZoeBakes, Zoe Francois details the inspiration behind her candied confections. While creating her rose-decorated almond Bundt cake, “My head was flooded with images of the red carpet dresses at the Oscars; Vintage Easter Bonnets and Bridal Showers,” she wrote. “That’s a lot of pressure for one little cake.”

The messages can also be a call to action. In a recent post, Amani Al-Khatahtbeh, an outspoken advocate for Muslim women, huffs: “The amount of wallah bros that use ‘You’re my sister in Islam !!!!’ to justify their entitlement to harass women they don’t even know about the way they dress,” adding an admonitory, “Sheesh do better, please, Brothers!”

Extended posts can also be part of a marketing strategy, as Michelle Obama grasped when earlier this year she began documenting the publicity tour for her “Becoming” memoir. On her feed she offered uplift: “We’ve all struggled with the balancing act that can take over days, years, or decades of our lives. And I want us all to remember that these are the moments and lessons that make us who we are, every little twist and turn, every little bump and bruise, and ultimately every joy …”

Such posts invite the kind of introspection that Instagram has encouraged only recently. “Instagram is a very twitchy medium where you click, click, click and then go on to the next thing,” said Richert Schnorr, the director of digital media for the New York Public Library. “On social media, people are craving something more.”

It may be a sketch, or even a novel. In partnership with Mother, an advertising agency in New York, the library recently published “Alice in Wonderland,” “The Metamorphosis” and “A Christmas Carol” on Instagram. “When Alice was published,” Mr. Schnorr recalled, “we had well over 100,000 new followers in 48 hours, a spike unlike anything we’ve ever seen.”

We want to be seen — and heard

Beefed-up diary entries, too, have been such a hit that an app, Instagram Memoir, briefly surfaced as a $5 download on the Apple Store, its objective to encourage journaling by students in grades 3 to 12.

Extra-long captions can be an outlet for news or, in darker instances, hate-mongering and sociopolitical extremism, as Taylor Lorenz observed in The Atlantic. But it also offers space for soul-searching.

Mr. Mullen, the fashion stylist, introduced his Insta-diary almost three years ago. “I thought: ‘Here I am in my 50s. I have a career that’s good, a mortgage, a partner — all these good things in life,’” he said. “But I felt that somewhere along the way I had let go a little part of what I am.”

He found that posting his largely unfiltered reflections was both healing and liberating. “This is the only way that we can really connect with people,” he said. “It’s the only way that we can talk honestly about our human condition, instead of posting a photo of our feet in the air in first class on Air Emirates.”

Paul Cavaco, a celebrity stylist, advances a sophisticated variation on the journal entry, drawing back the curtain on the behind-the-scenes antics of some legendary fashion shoots, not least a Steven Meisel portrait of Madonna in a bra and crinoline, shot in the early ’90s for Rolling Stone.

For the photo the pop queen needed some jeans, Mr. Cavaco recalled, so he stripped off his own and handed them over, darting around in his skivvies for the duration of the shoot.

“We’re so inundated with images, but we have no idea of the back story,” Mr. Cavaco said. His meandering captions, which add up to an engrossing memoir of a life in fashion, triggered a jump in engagement. “There were comments, lots of them,” he said. “I would find myself going to read them. It spurred me on.”

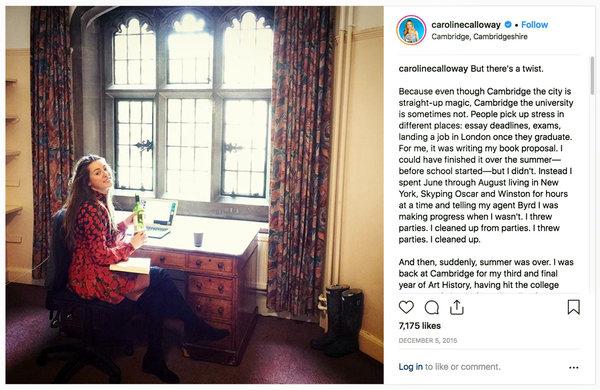

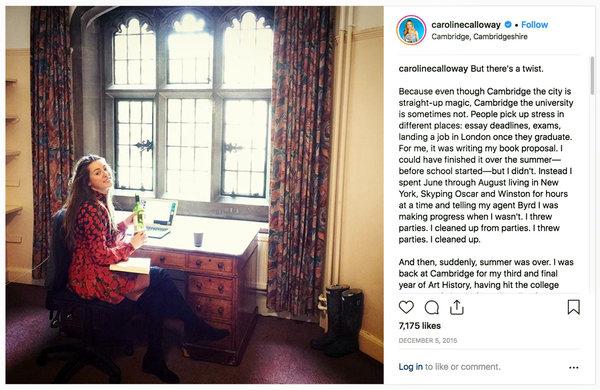

But if we tell ourselves stories in order to live, as Joan Didion famously observed, we also tell them in order to brand. No need to clue in the 27-year-old Ms. Calloway. A self-proclaimed progenitor of the Insta-memoir, she began to draw notice in 2015, documenting her adventures and romantic exploits while an art history student at Cambridge University.

Her knowing, deliberately self-deprecating, fablelike reflections (they are archived on her account) were a smash with her followers, many of whom could only dream of sharing a life style that encompassed gamboling on the college green or watching her boyfriend mount a polo pony.

She has haters, for sure (who wouldn’t, with more than 800,000 followers?). She was publicly chastised for defaulting on a $500,000 book deal based on her Instagram feed, having already spent $100,000 of her advance. Earlier this year, others called her out for failing to deliver on a zealously promoted multicity series of creativity workshops that were to be highlighted by lofty talks, girlie lunches and gift bags.

When the series did not live up to its promise, Ms. Calloway was branded a scammer, the tour tartly labeled “Fyre Festival 2.” She was quick to apologize, ascribing the debacle to her own lapses in organization and follow-through. These days she is offering a less cosmeticized version of herself on Instagram Stories.

“Looking back,” she said in an interview, referring to her earlier posts and a rarely mentioned Adderall addiction, “I think how much more vulnerable I could have been with my audience.”

In exposing her frailties she is hardly unique. “My period is coming. My face is broken out, and I’ve laid on the floor crying a lot in the last 2 weeks,” Sophie Gray, a 24-year-old fitness guru, wrote on her Instagram. That abject confession appears alongside a close-up of her seriously blemished complexion.

“Flawed? Nah, human,” she wrote in the companion text.

Like many of her contemporaries, Ms. Gray, who promotes brands on her feed from time to time, relies on those texts to tout her genuineness. “You are making yourself vulnerable to build an audience,” she said in an interview. “Instead of posting content to be just looked at, I try to open up dialogue with my readers.

“On Instagram, people want to be seen — and to be heard,” she said. To that end, she is exploiting the medium as a place to wax chatty and showily candid about her own and her readers’ body image issues.

High time, it seems. “I could not keep up with the facade that social media creates,” Ms. Gray said. “It’s exhausting to pretend that things are O.K. all the time.”