On a warm day in early July, Ed Houlihan guided kayakers on a four-mile trip on Cape Cod from Popponesset Bay up the Mashpee River to a freshwater pond. It was three hours of paddling round trip, but afterward Mr. Houlihan, 83, felt no worse for wear — at first.

Five days later, his left shin was red and sore, his body was aching, and he had fever and chills. Doctors diagnosed him with a Shewanella algae infection, a bacterium that thrives in brackish water.

“Everyone worries about sharks in the water, and what got me was this tiny micro-organism,” Mr. Houlihan said.

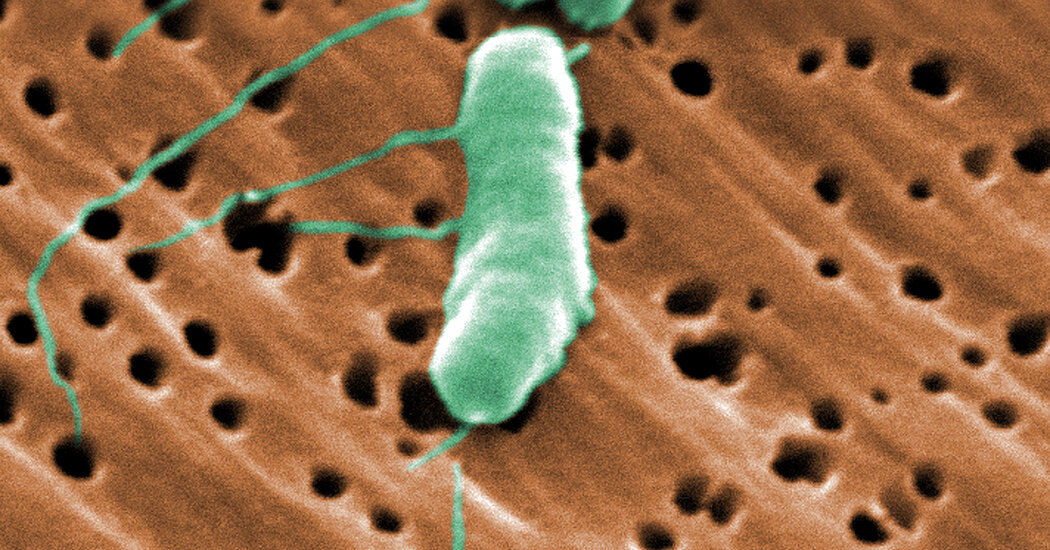

Water-borne pathogens like S. algae appear to be turning up more often in the Northeast. Another serious infection, the flesh-eating bacterium Vibrio vulnificus, killed three people in the New York area this summer. The bacterium enters the body through scrapes or cuts; it can also be ingested by eating raw shellfish.

While it was once seen mostly around Florida and the Gulf of Mexico, V. vulnificus seems to be colonizing new waters. “It used to be highly unusual north of the Carolinas,” said Jim Oliver, a microbiologist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. “Now it’s fairly routine.”

He is an author of a recent study that found that V. vulnificus wound infections increased eight-fold in the eastern United States between 1988 and 2018, from 10 to 80 infections per year. Cases were identified an average of 48 kilometers farther north each year, according to the study, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

By 2018, infections caused by various Vibrio species (there are at least a dozen) were reported regularly as far north as Philadelphia. There were more than 1,100 Vibrio wound infections between 1988 and 2018, and 159 deaths. The infections have become a “microbial barometer of climate change,” according to the paper.

Earlier this month, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged medical providers to consider V. vulnificus to be a possible culprit if they see a wound infection in someone who has been in coastal waters, and to initiate aggressive antibiotic treatment immediately. The infection can kill in as little as a day.

“Many bacteria, including Vibrio, are more abundant in warm waters, and we know that water temperatures are increasing, and we had record-breaking heat waves this summer,” said Joan Brunkard, an epidemiologist at the C.D.C.

A recent study that tracked Vibrio and Shewanella infections between 2010 and 2018 in Denmark found that most cases occurred in years when seawater temperatures were high.

These infections are rarely acquired domestically in northern European countries because coastal seawater is mostly too cold to support high bacterial levels. But the warming of low-salinity coastal waters in the Baltic Sea has fueled growth of the bacteria, increasing the risk of human infections, the authors said.

The number of infections was higher during warmer summers, compared with colder summers, the researchers found. Vibrio and Shewanella infections increased during every summer in the study period, the paper reported. The summers of 2014 and 2018, which saw very high sea surface temperatures, coincided with a higher number of infections.

The study found that older people, men and boys were at greater risk — the boys probably because they were more likely to have gotten scratches or wounds while engaging in activities such as fishing or rowing, and the bacteria need only a small entry point to get into the body.

Ear infections, many caused by S. algae, were more common than wound infections, according to the Danish study, which was published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. But V. vulnificus more often led to sepsis, a life-threatening condition that results when the body’s defenses injure its own tissues and organs. (Limb amputations are sometimes necessary.)

The problem is not just that waterborne pathogens may be heading to new waters. The populations in the United States and Europe are also aging. Older people, the immunocompromised, people with diabetes and those with liver disease are particularly vulnerable.

For them, “it’s not a good idea to go wading in brackish waters in really warm times,” Dr. Brunkard said.

People who are older or who have chronic conditions should avoid swimming at any time if they have even a small open cut or opening in the skin, the C.D.C. says. Even a small puncture point, like a recent piercing or tattoo, can open the door to a pathogen.

Mr. Houlihan believes his cracked toenail was all Shewanella needed. Since his leg became infected, he has been hospitalized three times, for a total of 26 days.

During the first hospitalization he developed a high fever and sepsis. Although the fever dropped and Mr. Houlihan was sent home, his pain was intense, and he was back in the hospital on two more occasions.

Large blisters developed on his lower leg, and he had to undergo surgery to remove the damaged tissue, leaving an indented crater that wrapped around his lower shin.

Now there is an open wound on his leg. The bandages must be changed daily, and though he is able to walk, it is with some difficulty. The treatment is not yet over: He is scheduled for more surgery and a skin graft later this month, and will then start a regimen of physical therapy.