Demna, the mononymic designer of Balenciaga, that former harbinger of all things haute and cool that experienced a highly public fall from grace last winter, simply cannot resist a visual metaphor. His collections became famous as comments on the world around us and then infamous: He sent refugees trudging through a maelstrom after Russia invaded Ukraine; fetishized capitalism in the New York Stock Exchange; and then veered uncomfortably close to associating children with S&M when he posed a youngster amid adult “toys,” reminding the watching world that those who thrive by the viral image risk dying by it.

So what does it say that his resort collection, released digitally on May 30, features a video of models emerging from the vaulted wooden doors of the Balenciaga headquarters on Avenue George V, walking back into the world in their shoulder pads, hoodies and beaded gowns, only to be doused by a sudden downpour?

Coming three days after the end of a Cannes Film Festival in which more Balenciaga appeared on the red carpet than it had since last November, the message is pretty clear: Balenciaga is in the midst of its comeback, baby.

Welcome to the next stage of The Return. Or, as Mosha Lundström Halbert called it on TikTok, the “Balenciagassance.” If the Balenciaga powers that be can pull it off, they will have added a new chapter to the story of early 21st-century cancel culture, becoming not just a case study on mismanagement in a crisis, but one on how to strategize a recovery without the public defenestration of the decision makers involved.

As you may remember, the erstwhile hottest brand in the world fell into disrepute after a troika of events — its close relationship with Ye before his turn toward public antisemitism and racism; and a pair of ad campaigns that viewers claimed promoted pedophilia — had it teetering on the brink of disaster. Balenciaga products were burned on social media; Kim Kardashian condemned the choices; sales during the crucial holiday period dipped markedly. Even in a fashion world regularly troubled by problems with appropriation and offense, the situation was extreme.

Caught up in a whirlwind of public opprobrium, Demna and the brand’s executives seemed unsure how to react, before finally offering up statements of public apologies and self-recrimination. Then, after what seemed like a self-imposed timeout, they came tiptoeing out of the shadows with a show in February: a stripped-down march of the penitents involving no sets or social commentary, just clothes.

But then came the Met Gala and Demna’s first major public appearance, albeit one in a fashion safe space, where he hosted a table for young designers who could not afford their own tickets. Then came Cannes and the return of red carpet names to the fold.

It was clear that a master plan of sorts was unfolding. One that was tactical and considered and with some of fashion’s most influential power players carefully pulling public strings.

Anna Wintour, for example, who very deliberately invited Demna to the Met and who has made something of a personal cause of second chances: masterminding John Galliano’s return to fashion after he was fired from Dior thanks to a drug-and-alcohol-fueled antisemitic rant, as well as supporting Georgina Chapman after the crimes of her former husband, Harvey Weinstein, tarnished her brand, Marchesa. Indeed, Ms. Wintour said, she was “thrilled” to have Demna attend the Met, citing his “sincere” apologies and commitment “to making changes at the house.

“I’ve always thought part of owning up to one’s mistakes is to not hide away, but to be honest — and go out and face the world,” she said.

Her embrace sent a signal to the rest of the fashion world, as did the fact that François-Henri Pinault, the billionaire chief executive of Kering, the luxury conglomerate that owns Balenciaga, wore a Balenciaga tuxedo to the Met rather than one of his many other brands, such as Saint Laurent, Gucci or Brioni. It was a public sign of his commitment to the brand and its designer.

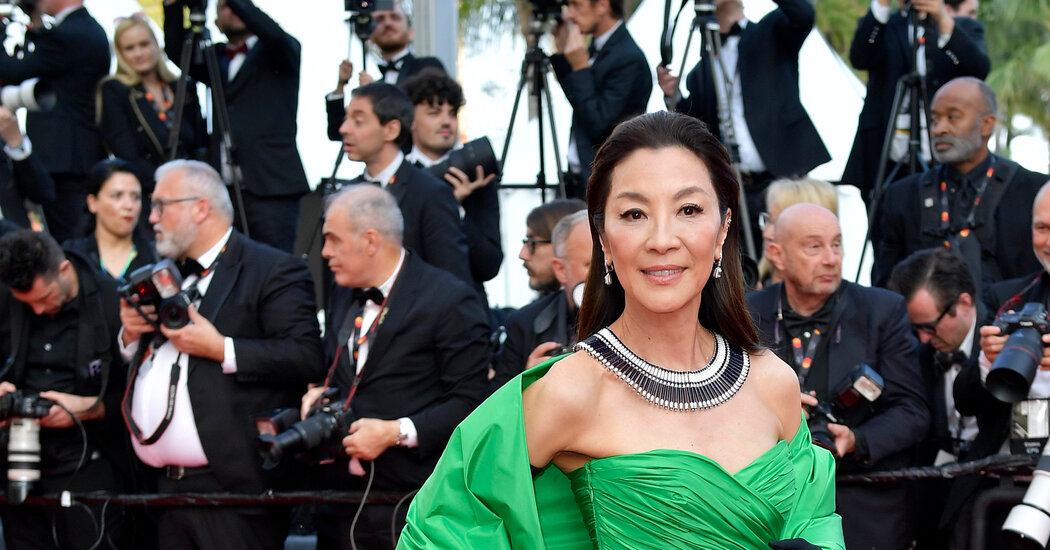

Mr. Pinault doubled down on his support at Cannes, once again wearing Balenciaga “on purpose,” he said. And it wasn’t just Mr. Pinault: His wife, Salma Hayek Pinault, also wore Balenciaga, as did Michelle Yeoh, Isabelle Huppert, Alton Mason and the French singer Yseult, in red carpet images that would be captured and sent around the world, putting their brand equity where Balenciaga’s was.

As to why, Cédric Charbit, Balenciaga’s chief executive, said they were all wearing custom looks and “that happens through long-term relationships.”

“It’s not an overnight process, and it needs to be meaningful,” he said. Suggesting, again, that the decisions were planned gestures of affirmation.

The chosen site seemed a carefully calibrated choice as well, given that an equally if not more controversial return — that of Johnny Depp to the big screen — also took place at Cannes, effectively paving the way. (Also, the brouhaha over Balenciaga had always been lower in Europe than it was in the United States, so it made sense to start the comeback there.)

Admittedly, when pictures of Ms. Yeoh and Co. in their Balenciagas appeared, there were a few social media comments taking them to task, but any negative reaction was far outweighed by the fire emojis. Overall, backlash was almost nonexistent. Diet Prada issued not a peep.

The outrage mob had, it seems, moved on. Luca Solca, a luxury goods market analyst, compared the Balenciaga situation to the Gucci “blackface difficulty” of 2019. “We have seen in the past that media mishaps have an impact for two to three quarters and then normalize,” he said. He added that he expected Balenciaga to be “home and dry by the second half of 2023.”

Now the question is whether Balenciaga can recapture the buzz and sales it generated before its crisis, a more complicated conjuring trick to pull off. It is one that requires the alchemical combination of products and desire that Demna once generated by upending all expectations and challenging stale ideas of “beauty” and “luxury.”

While the cruise collection had some of that embedded within its signature oversize suits, puffer opera trenches and diva gowns — “drawstring” bags that looked like the string bags used to tote grocery produce; “towel” wrap skirts that looked like bathroom towels — such pieces no longer seem revolutionary. Like the ready-to-wear collection in March, they’re familiar.

That’s OK. As Hermès has proved, there is profit in consistency, if not excitement. And Demna can create truly gorgeous, sophisticated clothes, with the purity of line synonymous with the house. See one fan-pleated silk dress with winged sleeves that simultaneously suggests the body while framing it like a bas-relief. But the magic that was once there, that sense of gleeful, liberating, absurdist challenge?

That still hasn’t come back.