The first sign that something is amiss at the Atlantis resort on Paradise Island comes before even stepping inside: The Bahamian flag perched on the roof is flying at half-staff.

The nation’s flags, even the one above the luxury 3,800-room water park and hotel, have been lowered in honor of the 51 people who died in the first days of September in Hurricane Dorian, a category 5 storm that obliterated Great Abaco Island and flooded a good part of Grand Bahama. But even as hotels donate money and Delta Air Lines and cruise ships evacuate survivors and deliver relief supplies, the travel industry in the Bahamas is desperate to convey the message that the natural disaster, as terrible as it was, occurred 100 miles from Nassau, its top tourism destination.

This nation in mourning is also a nation dependent upon tourism. The Bahamas needs its tourists back.

“I struggled with that coming here,” said Samantha Ping, of Kentucky, who visited the Atlantis resort last weekend with her husband, who was attending a conference. “I am going to be laying by the pool, while people an island away are struggling for food and water?”

Ms. Ping found a solution that would both ease her conscience and save her vacation: She took the trip and used her free time at Atlantis to make sandwiches for storm survivors. Atlantis offered up a sizable donation and one of its kitchens to World Central Kitchen, a relief organization that delivers hot food and sandwiches in disasters around the world. It is slow season in the Bahamas, so while small groups of people lingered at the swim-up bar, and a few managed to wrestle up enough people to play volleyball at the pool, a bustling kitchen inside prepared meals for a disaster that seemed a million miles away.

“Me and six other girls made 5,000 turkey sandwiches and 5,000 tuna sandwiches,” said Christine Stramiello, a waitress from New Jersey who arrived at the Atlantis resort just days after the hurricane hit for a three-week vacation. “I would feel so guilty if I came here and didn’t help.”

Ms. Ping and Ms. Stramiello are among the thousands of people who had already booked vacations to the Bahamas and were left with the unpleasant choice of whether to cancel their trips or travel knowing tragedy had struck. Travelers called and emailed hotels to find out whether it was safe. Was the power on? Would evacuees be sharing the hotels with tourists?

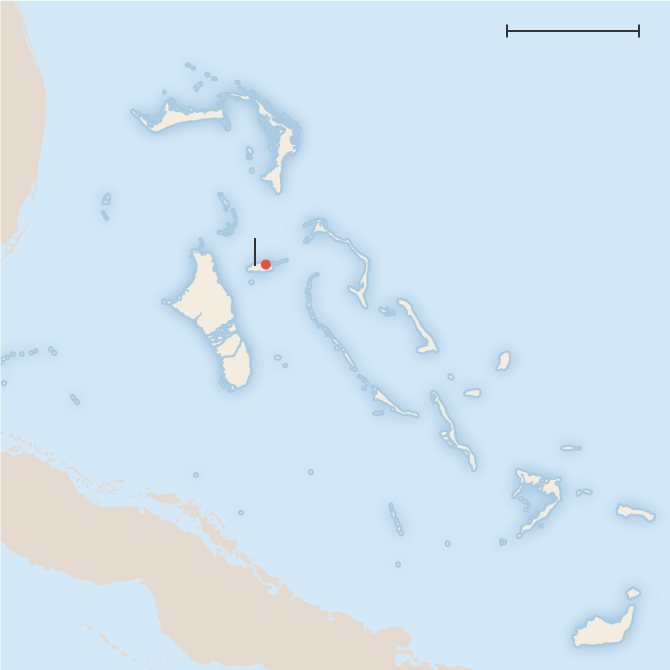

Many travelers were scared off and scuttled their plans. Hotels across the 700 islands that make up the Bahamas have seen “double-digit and triple-digit” cancellations, the tourism ministry said — even those located nowhere close to the destruction. In response, the ministry released a map showing that of the 16 touristic islands in the Bahamas, 14 are “open for business.” Popular destinations like Eleuthera, Exuma and Bimini were also unaffected by the storm.

“If a hurricane would hit Jacksonville in Florida, it wouldn’t mean that you wouldn’t go on vacation to Miami or Fort Lauderdale,” said Dionisio J. D’Aguilar, the Minister of Tourism and Aviation. “That’s the analogy we are making. Unfortunately, people are geographically challenged.”

The 700 islands that make up the Bahamas are of varying sizes and stretch over 750 miles. Hurricane Dorian knocked the power out on Nassau for a few hours, but left no damage.

Mr. D’Aguilar acknowledged that some people, like Ms. Ping, know that places like Nassau fared well in the storm, but they still feel that it is “inappropriate in a time of tragedy and calamity” to vacation there.

The opposite is true, he said.

“More than ever we need you to come on vacation,” he said. “That’s the only way we can help our brothers and sisters in the north.”

While still trying to strike the balance needed for a period of solace, the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism is in the midst of a “soft launch” campaign that tries to push the idea that the country — most of it, anyway — is open for business.

Some 4 million people visited the Bahamas the first six months of this year, contributing to roughly half the country’s gross domestic product. About 20 percent of those travelers visited Abaco and Grand Bahama.

Abaco, which had just launched direct flights from Charlotte, Atlanta, Miami and Fort Lauderdale, was struck particularly hard. Nearly 300,000 tourists had visited there from January to July this year, but that business is now shut down for the foreseeable future.

Bahamas is bracing for a huge hit to its national economy, just at a point when it needs an influx of cash.

“If they don’t come, we are not going to have revenue to rebuild,” said Ellison “Tommy” Thompson, the deputy director general at the tourism ministry. “We really need them to come, stay an extra day and spend an extra $50.”

He has been spreading the word on social media and in media interviews, and the country will continue a “Fly Away” advertising campaign begun earlier this year that features the singer Lenny Kravitz. Once the hurricane season is over, more aggressive promotion, including billboards and train station advertising, is also planned.

“We are sensitive to the fact that so many of our brothers and sisters lost everything,” Mr. Thompson said. “But we’ve got to be firm. We are the Ministry of Tourism. Our job is to attract visitors to the Bahamas. It might sound cold, but if we don’t have visitors coming in, everybody is going to suffer.”

Benjamin Davis, the general manager of the Warwick Hotel on Paradise Island, said the hotel has seen about 8 percent of its bookings canceled.

“We have had people calling to ask if we are going to be open in January 2020,” he said. When Dorian struck, Warwick never closed.

Great Abaco

Grand

Bahama

Atlantic

Ocean

New providence

Great Exuma

Inagua Is.

He walked around the property, where a group of women were celebrating a 40th birthday party and a waiter showed off his chops as a singer.

A few miles away in downtown Nassau, where the cruise ships dock, tourists shopped for trinkets, oblivious to the disaster. Cruise ships have continued to sail to Nassau, although Freeport is no longer available for disembarking.

Pam Smith, a retired nurse from Long Island, N.Y., said it was a difficult decision to go forward with her vacation plans. She realized that her tourist dollars were needed not just by the government, but also by hotel workers who have taken in relatives who lost their homes.

“At first, it’s like, ‘What am I doing here, when people are coming here to Nassau to stay in shelters?’” she said. “Do I really want to be here when such a tragedy happened in another part of the Bahamas? But look at all these people working here. They need us here.”