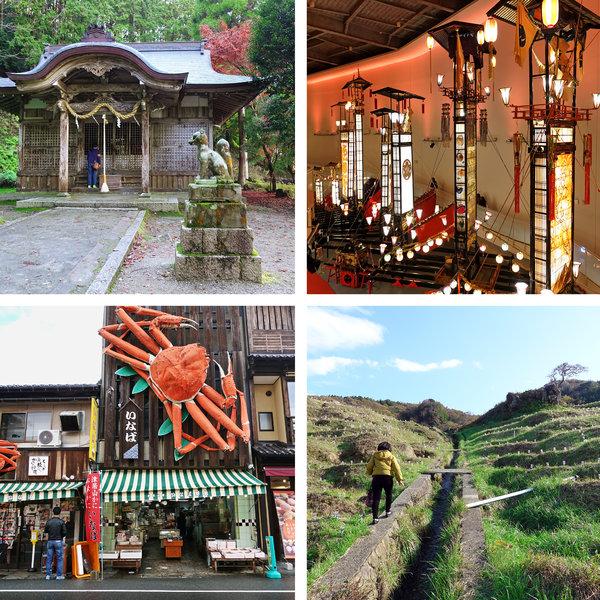

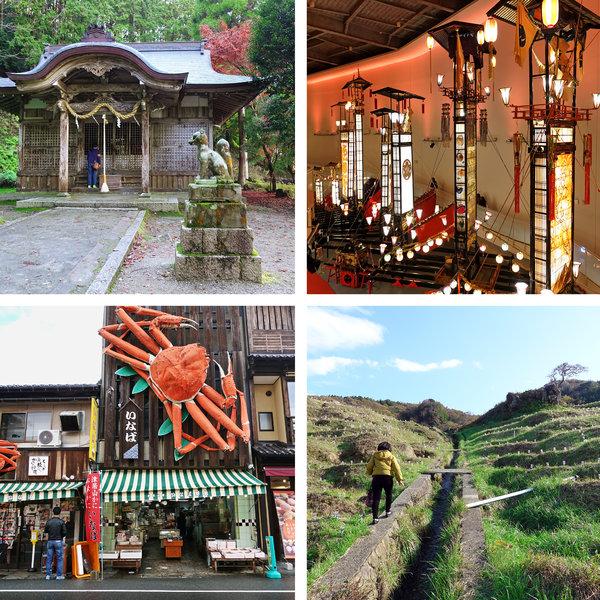

From top right: Lantern floats used in parades at the Wajima Kiriko Art Museum on the Noto Peninsula; terraced rice paddies, also on the peninsula; street scene in Kinosaki, which is famous for snow crabs; a Shinto shrine above the town of Izushi.CreditJada Yuan/The New York Times

Our columnist, Jada Yuan, is visiting each destination on our 52 Places to Go in 2018 list. This dispatch brings her to the west coast of Honshu in Japan (no. 27 on the list); it is the 48th stop on Jada’s itinerary.

Learning to walk

They looked so innocent: planks of wood that attached to my feet with cloth thongs, like flip-flops. But their contact surface with the ground was two blocks of wood, neither of which was under the toe. I pitched forward with each step and felt like I might launch face first into the ground.

I had spent some 39 years of my life believing I knew how to walk, but click-clacking down the streets of Kinosaki, Japan, in geta sandals, I wasn’t so sure anymore.

Over my clothes, I wore a yukata robe, or lightweight cotton kimono, that had been so complicated to put on, it came with illustrated instructions. A staff member from my traditional Japanese inn, Tsukimotoya Ryokan, tugged and tied it into place. “No, no, no,” said the woman, who was half my height, as she put the right-side flap over the left. Then she reversed them, nodded, and cinched it all together with an obi sash, “O.K., O.K. O.K.”

As I ventured outside, I heard loud, assured click-clacking behind me — two women in the same outfit that I was wearing. They were sisters from Singapore and moved like gazelles in their getas. I wobbled behind them, and then nearly lost my footing as I took in the scene near the lantern-lit Otani River winding through the city. It was a veritable thoroughfare of yukatas and getas, in an array of colors, on visitors young and old, shuffling, striding and practically skipping through the night.

People come from all over Asia and beyond to soak in Kinosaki’s seven onsen, or public hot spring baths, and pretty much everyone does it walking around in a robe all day. The city is one big inn. The ryokan you stay in is your individual room and the streets are like the inn’s corridors. It’s all very romantic until it hails and rains.

I had come to Kinosaki, on the western coast of Honshu, Japan’s biggest island, though, not for dressing up, but on a kind of pilgrimage. As a Japanese friend put it to me in an email, “Don’t they have that Buddha that’s only unveiled to the public every 33 years?”

The morning after I’d arrived, I took the Kinosaki Ropeway (a cable car) high up Mount Taishi to the Onsenji temple, home to the 1,300-year-old Kannon Buddha, the Goddess of Mercy. She has 11 faces, 10 in a crown to signify her wisdom, and was carved from the top of a mystical tree that produced three Buddhas, of which she is the only original one left. This April began her unveiling, which will last for three years, until she goes back into hiding for another 30 years.

Midway up the ropeway, hail had started coming down, and I rushed inside the temple. There, with the help of a translator, I spoke with Ogawa Yusho, the resident monk, who was born in the temple and is now raising his family there. He’d grown up hearing the legend of Dochi Shonin, a priest who came to this very spot in 738 and prayed for 1,000 days for the health of the people here — and on the 1,000th day, an onsen sprung from the ground. It is said to be Mandara-yu, the oldest of the seven on Kinosaki’s onsen circuit.

Before modern medicine, ill people would trek to Onsenji temple, pray to the spirit of Dochi Shonin, and then bathe, naked, with a wooden ladle in the hot springs. For those too infirm or disabled to make the trek to Onsenji, a string stretches from the arm of the Buddha all the way into town, so you can indirectly touch the Buddha as you pray. Ogawa Yusho gave me a bracelet of the string to bring me luck on my travels.

Once there, the ritual is to strip down, shower while sitting and then soak in those healing waters, surrounded by bodies of all shapes and sizes. (Onsen are divided into all-male and all-female sides.) I was struck with the ease of nudity, how young girls splashed around with their mothers and big sisters and grandmothers, and what an impact that must make on their self-image, to know that bodies are all different and we all have one. The hot spring water warmed away the foul weather.

As I left, I put on my yukata, thinking of the words I’d heard in the ryokan: left-side over right, “O.K., O.K., O.K.,” and stepped out into the thoroughfare that seemed like a reversal of time. The onsen were a little hot for me, but I could walk around in a robe forever.

Adventures in seafood

His name was Sushi Tiger. He was 76 and he’d been studying the art of cutting raw fish for 50 years. Why didn’t I come in and take a seat?

I was the only person in his narrow restaurant, breaking a cardinal travelers’ rule to follow crowds to the best food. But I’d already been wandering the streets of Kanazawa, the capital city of the Ishikawa Prefecture, for 20 minutes in search of sushi and a kind young man had brought me here, so who was I to mess with fate?

Sushi Tiger, who also goes by Takashi, wrapped a twisted white bandana around his forehead as he prepared my dinner. He spoke little English and I spoke almost no Japanese, so we communicated by writing on napkins, pointing at a sign with pictures of sushi and Google Translate, which is even more hopeless at Japanese than it is at other languages. At one point he brought out a book of cartoons used for teaching English to school children and taught me a few Japanese phrases, while serving me sake. I was glad to be his only customer.

I am not an adventurous eater, particularly when it comes to seafood; I was a vegetarian for a long time, in New Mexico, which has no sea. But when I set out on this 52 Places trip, I made a vow to overcome my pickiness, which meant eating a few insects and a small slice of wallaby (I still feel guilty). Japan, I thought, would really test those limits.

Under the tutelage of Sushi Tiger and Kawai, another Kanazawa sushi master at Takasakiya Sushi, though, I ate melt-in-your-mouth maguro (tuna) and sucked green eggs from the shell of amaebi (sweet shrimp). I also learned that I do not like eel or squid or anything I have to work hard to chew.

In my Kinosaki ryokans, at lavish kaiseki dinners, the learning curve was steeper. I’d sit down to a tray filled with 20 little plates and no one who spoke English to guide me through them. What order was I supposed to eat them in? Did any of them get dipped in soy sauce? So I’d try first and ask questions later. It turns out I am not a fan of preserved fish eggs melded into a rectangular cake, but I’m O.K. with tender fish intestines.

The big reason Kinosaki still has such a thriving Asian tourism business in the winter is that snow crab season starts in November, and lasts only a few months. People come for the crab and stay for the onsen. A good crab can sell for up to $300.

I was lucky enough to have a snow-crab kaiseki dinner served to me in my room at Sinonomesou Ryokan, where I sat at a low table on a bamboo floor mat. I had been relying on guidance from young members of the Kinosaki tourism board and invited them in to eat my crab. Nakada Naoki, who had grown up nearby, showed us how to suck the meat out of the claws.

Easier to navigate were sweets and bento boxes. I tried buckwheat-battered red bean cakes and soba-flavored ice cream in the castle town of Izushi, famed for its soba, and became a huge fan of to-go sushi hand rolls at Family Mart convenience stores. What I’ll remember this Japan trip for is trying shrimp for the first time in probably 15 years.

Northern exposure

On my last day, I wanted to see the coastline — which I had heard was spectacularly beautiful along Noto Peninsula near Kanazawa. I didn’t have the right paperwork to rent a car, public transportation seemed difficult, and there were no English-language tours. So I paid $66 to jump on a bus tour that was only in Japanese, hoping the scenery required no explanation.

Our route took us to Shiroyone Senmaida, a set of more than 1,000 terraced rice paddies on the seaside that has been registered as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System; and for a drive along Chirihama Nagisa Driveway, five miles of sea-packed sand, one of the few places where ordinary cars and busses can speed right along the shore.

But first thing was a visit to the 1,000-year-old morning market in the seaside town of Wajima. Locals bought fresh fish, and grilled it over coals in a designated area. I tried yuzu soft-serve ice cream and maru-yubeshi, a local candy made of orange peel, and mostly wandered around in a mute, dazed state. I followed a crowd to a shop called Tohka-doha selling lacquerware chopsticks, a traditional craft, in which the artisan covers a piece of wood with up to 100 layers of lacquer, and then shaves off a portion of the surface to reveal a kaleidoscope of colors.

Before long, the 79-year-old, English-speaking owner, Yatsui Kiyoshi, emerged. When he heard I was on a long trip, he pulled out a weather-beaten Rand McNally atlas and told me he had studied nuclear physics at Cornell, and driven across the United States to spend two years in Los Alamos, N.M.

My hometown.

He loved the mountains and the tequila but thought it was too hot, and he missed Japan and his family. So he came back to continue a life in nuclear physics and carry out his legacy as a fifth-generation lacquerware artisan.

His wife took some pictures of us, which he emailed to me with a note about what a small world it is and how wonderful it had been to find someone with connections to New York and New Mexico. Then he reminded me, for about the fifth time, not to put the chopsticks I’d bought in the microwave.

Practical Tips

Trains Japan’s network of trains is famous, and their JR Pass, which offers unlimited rides in cars with unreserved seats, is worth the cost. Purchasing online and having it shipped to you is the cheapest option ($254 for seven days covering the whole country), but the passes are also available at major stations. If you’re only traveling in a single region, you’ll save money buying a limited version. (I got a seven-day, Kansai-Hokuriku JR West pass for $140.)

JR Passes don’t work in automated entry gates, so you’ll need to find a gate agent to waive you in and out of each train. Bullet trains cost extra on limited passes. If you have luggage, board in the rear of the car; there’s storage behind the back row of seats. Alternatively, use the coin lockers in the stations, or employ a hands-free luggage transportation service that will send your things on to your next destination.

A word on exhaustion Multiple transfers over a six-hour train trip between Kinosaki and Kanasawa meant no time for naps; I had to set alarms on my phone to make sure I didn’t nod off and miss my stop. If you must nap while you travel, consider taking a bus. Also, most hotel checkout times are 10 a.m. Try to stay in one place multiple nights so you can sleep in one morning.

Driving Renting a car would have been a great way to see Western Honshu, but you need an International Driving Permit. It’s cheap and not hard to get, but easiest if you obtain it before you leave on your trip.

Money Matters For a country that seems so futuristic, much of Japan outside Tokyo and major cities seems to be a cash society (even in Kanazawa). I used my credit card twice. Even hotels I’d booked online would ask to be paid in cash or with PayPal. A.T.M.s are plentiful, but you must use the international ones next to post offices if you don’t have a Japanese bank.

Rubbish Japanese food is beautifully packaged, which creates a ton of waste. I was astounded with how many plastic bags I’d wind up with over the course of a day. To mitigate that, carry reusable bags.

There’s also a surprising lack of trash cans in public spaces. The local expectation is that you pack your trash, and dispose of it when you get to a place with garbage and recycling bins.

Stay If you can’t stay in a traditional ryokan, consider a business hotel with an onsen, or a shared hotel, essentially a hostel. In Kanazawa I enjoyed my tiny capsule bed with a blackout curtain and locker in HATCHi Share Hotels; $20 for a 20-person dorm room. My experiences with Kanazawa guesthouses were very clinical; I never met another person, and let myself in and out via a lockbox. Not a fan.

Eat Sushi and seafood is the main draw along the Honshu coast, but remember, the Tajima mountain region near Kinosaki is where Kobe beef came from. Also look for Stork Natural Rice, grown free of pesticides that killed off Japan’s wild Oriental White Stork population. In Kanazawa, I was thrilled with the pizza and beer at Oriental Brewing, and a tiny ramen shop, Wakadaisho, with an ebullient owner serving up laughs and bowls of goodness late at night on the Asano River.

Previous dispatches:

1: New Orleans

5: Trinidad and St. Lucia and San Juan, P.R.

6: Peninsula Papagayo, Costa Rica

7: Kuélap, Peru

12: Denver, Colo.

14: Seattle

15: Branson, Mo.

16: Cincinnati, Ohio

18: Buffalo, N.Y.

19: Baltimore

20: Iceland

21: Oslo, Norway

22 and 23: Bristol, England, and Glasgow, Scotland

24 and 25: Tallinn, Estonia, and Vilnius, Lithuania

26 and 27: Arles and Megève, France

28 and 29: Seville and Ribera del Duero, Spain

30: Tangier, Morocco

31: Road Trip in Western Germany

32: Ypres, Belgium

33: Belgrade, Serbia

34: Prague

36: Südtirol, Italy

37 and 38: Emilia-Romagna and Basilicata

40: Kigali, Rwanda

41: Zambia

42 and 43: Top End, Australia, and Tasmania

44: New Zealand

45: Fiji

47: Gansu, China

Next dispatch: Chandigarh, India

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.