The 52 Places Traveler

The 52 Places Traveler follows his stomach through the city of Houston, finding a staggering diversity along the way.

By Sebastian Modak

Quy Hoang, Houston’s first Vietnamese-American pitmaster, spends most of his days manning the smoker at Blood Bros. BBQ in Bellaire. CreditSebastian Modak/The New York Times

Our columnist, Sebastian Modak, is visiting each destination on our 52 Places to Go in 2019 list. He arrived in Houston after stops in Puerto Rico and Panama.

At first glance, much of Houston looks alike. Making your way out of the “Loop,” the I-610 highway that circles the city center like a shirt collar, skyscrapers give way to manicured office parks and strip malls, each seemingly a carbon copy of the last. But when you look a little closer, you notice that in one of those strip malls, all the business names carry the tonal accents of written Vietnamese. In another, two Indian restaurants sit on either side of a service specializing in money transfers to Central America. In a nearby parking lot, a family — the men wearing skullcaps and knee-length agbada shirts and the women in brightly-patterned hijabs — loads up a sedan with the ingredients for a meal that I imagine tastes like another home, thousands of miles away.

Houston is widely considered to be one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world. According to the city’s planning department, 48 percent of residents speak a language other than English — and more than 145 languages are spoken in the city. Twenty-nine percent of the population is foreign-born.

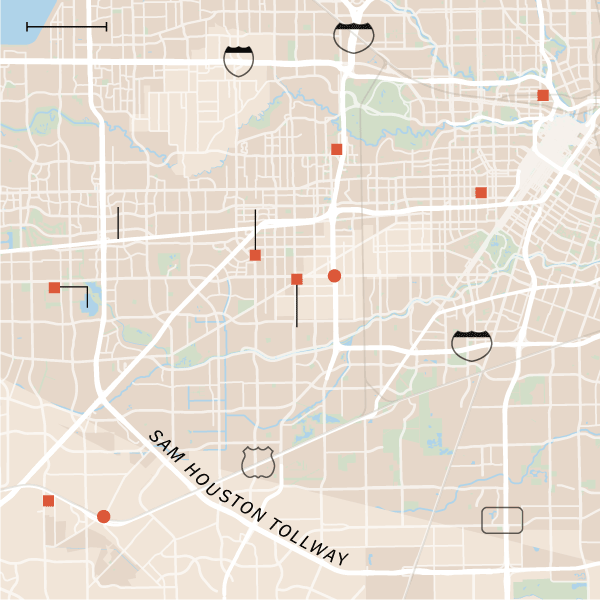

Diversity wasn’t the main reason Houston was on 2019’s 52 Places to Go list, but food and culture were. There’s the addition of the Drawing Institute to the brilliantly curated Menil Collection; a wave of new trendy Downtown food halls; the glitzy Post Oak hotel, home to a Rolls-Royce showroom and Frank Stella art — all rising out of the devastation left behind by Hurricane Harvey in August 2017. But unless you sequester yourself in the chic apartments of Downtown or the mansions of River Oaks, that diversity is everywhere you look — and everywhere you eat.

[Houston is Seb’s third stop on his worldwide tour. Read about his previous adventures, dancing in Puerto Rico and scuba-diving in Panama.]

So, feeling a kind of kinship with all those Houstonians who live between worlds based on my own unmoored and multicultural background, I leaned into it. I ate more than I should have and blew my Uber budget pretty quickly, but over three meals in a single day, I found a Houston I never imagined existed in the cracks between SUV-clogged freeways and oil-boom money.

Breakfast

“You’d fit in perfectly out here,” Robin Wong said to me, referring to Southwest Houston, home to Alief, where Chinatown blends seamlessly into Little Saigon; the Hillcroft area, recently named the “Mahatma Gandhi District” where South and Central Asians share retail space and public schools; and a host of other ethnic enclaves. “In this area, everyone’s a minority,” he said.

We had just sat down for a midmorning feast at Ocean Palace, a dim sum hall that in scope more resembles a castle (moat included) than a restaurant. I joined Robin, 43, and his brother Terry, 45, to learn about this neighborhood, Chinatown, where they had grown up. I also wanted to hear about their restaurant, Blood Bros. BBQ, which they run with their childhood friend, Quy Hoang, 46, who carries the distinction of being the first Vietnamese-American pitmaster in the city. (Mr. Hoang had celebrated his birthday the night before and for reasons that you can probably figure out, couldn’t make it for our allotted 11 a.m. time slot.)

The two brothers took control of the ordering, conferring in low tones as they checked items off a piece of paper. Over a spread of slick cheung fun rolls, scalding shrimp-filled har gow dumplings, chicken feet, turnip cakes, and more, the Wong brothers told me what it was like growing up in the most diverse section of the most diverse city in the U.S.

“My best friends, my childhood friends, are Chinese, Indian, Mexican, black, white—— You get exposed to so much growing up in Alief,” Robin said. “And people here, they love it; they love trying new things. It’s part of being from this neighborhood.”

Much of the attention around Blood Bros., which opened late last year in the suburb of Bellaire, has been on the owners’ backgrounds: Two Chinese-Americans and a Vietnamese-American pitmaster hitting the Texas trinity of BBQ — brisket, pork ribs, sausage — does not make for your average BBQ joint. That attention only increased when they started thinking more outside-the-pit. Some days, they will do a smoked turkey banh mi, which I can say firsthand is just as good as it sounds, the charcoal accents of the turkey providing a counterweight to the tanginess of the banh mi’s traditional fixings. They’ve experimented with Thai green curry boudins, a Cajun sausage traditionally stuffed with rice, liver, and aromatics, and their brisket fried rice is one of the restaurant’s most popular sides.

“It’s not about Asian-inspired whatever. We just make what we like,” Robin said, after pointing out some theoretical riffs he could pull on the dim sum spread out before us, only half joking. “We love the har gow dumplings. But what if we smoked them?”

Things to know

-

Houston might be the least pedestrian-friendly major city I’ve ever encountered. You will spend a lot of time in cars. Besides the relatively dense Downtown area, the city is very spread out. I didn’t rent a car and probably should have. If you choose to go carless, you’ll be taking a lot of Ubers and Lyfts, which thankfully are more affordable than in many cities in the United States.

-

That being said, I found Downtown a great place to stay. While, with the exception of some new food halls, there’s not all that much to do in the area if you’re not part of the business casual crowd, I found myself 15 minutes from everything, whether it was dim sum in Chinatown, the quirky bars and cafes of Montrose, or Cafeza, in the First Ward, which hosts a killer open jam session every Monday night.

Lunch

The first thing I noticed when entering Afghan Village, an unassuming restaurant in a strip mall in Hillcroft (a k a the Gandhi District) was the flags. Side by side, Afghan and American flags filled most of the free space behind the counter; a vertical American flag was draped across one corner of the restaurant, and another small one stood tucked into a corner just above the tandoor. The green, black, and red of the Afghan flag provided the color scheme for the whole space.

Omer Yousafzai, 41, opened Afghan Village over six years ago. He came to the United States in 2001, following his brother, studied law, and then spent years working with the U.S. military in a linguistics recruitment program. That brought him back to Afghanistan where American and Afghan soldiers alike craved home-cooked Afghan meals instead of the frozen food shipped in from the U.A.E. and elsewhere.

“That’s when I started thinking, ‘An Afghan restaurant could be a good idea,’” he told me as we dug into bowls of finely balanced lamb and chicken karahi (a lightly spiced curry), lamb chops, and fluffy naan fresh out of the tandoor.

There was never any question where he would open that restaurant.

“There’s something about Houston that attracts so many people,” he said. “It takes you in.”

When I asked him to try and pinpoint the reason for that, he identified the city’s diversity as a kind of self-perpetuating system.

“I think the reason is its diversity,” he said. “You can blend in here. You can claim this place is home and nobody questions that.”

Dinner

A childhood friend connected me with Iveth Reyes, 30, a social worker in Houston’s public school system, saying that she would know where to find legitimate Mexican food.

Ms. Reyes told me to meet her at Raizes Mexican Kitchen in Stafford, just outside Houston’s city limits, which she said was the place to try the real deal from Michoacán, the Mexican state where she was born before being brought over the border by her parents at the age of two.

The restaurant’s owner, Aristo Gaspar, 50, also from Michoacán, has been in Houston for more than 30 years and now operates three restaurants around the city. He brought out plates of carnitas tacos and enchiladas smothered in a chile reduction that more closely resembled mole than the salsa you’ll find at Tex-Mex spots. Looking up at the menu, I noticed that the Mexican dishes were listed right alongside chicken and waffles. Mr. Gaspar has learned to adapt to many tastes.

“This food still tastes like home,” Ms. Reyes said, as we spread habanero sauce on the plate of enchiladas.

She works in an elementary school in Gulfton, Houston’s most densely populated neighborhood, which has long been a first stop for new immigrants to the city. She didn’t have the same utopian view of cross-cultural harmony that I had encountered in others.

“The younger kids all get along; it’s like they don’t even know there’s a difference between them,” she told me. “But as they grow older they start forming cliques.”

Ms. Reyes told me that in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Harvey people put their differences aside and got to work repairing what was broken.

“You really saw how close-knit this city is and how it can come together,” she said. “People were out helping neighbors, or bringing their boats into different neighborhoods to help people get around.”

She pointed to her mother, Olga Farías, as an example. With electricity out after the hurricane, Ms. Reyes’s mother was called into the school cafeteria, where she worked, to clean out the freezers. Disobeying orders to throw away all the leftover food, she loaded up her car instead and drove around the city looking for people in need of a meal.

“It sucks that it took a tragedy to bring that out of the city, but it did,” Ms. Reyes said.