“I saw one collection that was in its entirety fake, and it had all been gathered 20 to 30 years ago,” she said. “There are some really well-known fakes that keep popping up.”

Reliable statistics on the size of the problem are hard to come by. Ms. Graham-Yooll dismissed as hyperbolic a 2018 study claiming that up to one-third of all rare single-malt bottles were fake. But she conceded that fakery is a sizable problem, and growing worse.

There is no shortage of anecdotes like the encounter at Acker. In 2017 a Swiss hotel drew notice for selling the world’s most expensive dram to a Chinese tourist. Subsequent analysis of the liquid, which was purported to be a single-malt Scotch made by the Macallan distillery in 1878, showed that it was a blended Scotch made sometime after 1970.

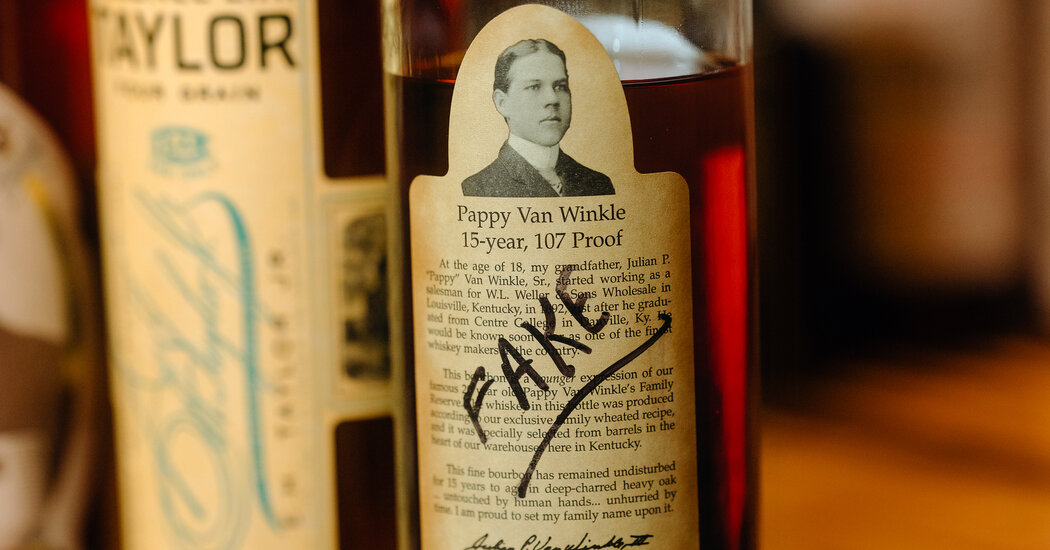

Like the Acker bottle, the fake Macallan had flaws obvious to an expert eye: the wrong cork, modern glass. In part because the field of counterfeiting is so new, Mr. Herz said, it’s not hard to spot counterfeits — drip stains on a paper label, for example, are a good indication that the bottle has been used before.

“Most people are lazy and impatient,” he said.

The whiskey trade has yet to see its version of Rudy Kurniawan, the prolific, highly skilled counterfeiter whose 2013 conviction for making and selling millions of dollars’ worth of precisely detailed fake Burgundy and California Cabernet rocked the wine world.

But it may be only a matter of time. Experts say they have seen an increase in the quality of counterfeits; Mr. Herz suspects that at least a few counterfeiters have inside connections at Kentucky distilleries, allowing them to build fake bottles from scratch, with pristine labels and expertly crafted closures.

A cottage industry has popped up in response, especially in Britain, promising high-tech countermeasures like through-the-glass chemical analysis, which allows sellers and collectors to assess a bottle’s authenticity without having to open it. But those are still in development, and years away from widespread use.