“When I heard Mickey sold the ski area,” Dave Hahn, a longtime member of the Taos Ski Valley ski patrol said, “I remember thinking, ‘That’s funny, a lot of us thought we owned it.’ ”

He was kidding, of course, but there was a poignancy to Mr. Hahn’s remark. Taos locals and longtime visitors to the New Mexico ski resort had the mountain to themselves for so long it’s almost as if some forgot their little jewel was a going concern, actually owned by the family of its longtime chief executive, Mickey Blake.

A crucible of native civilization, the town of Taos was a northern outpost of Spain’s colonial empire. The slopes at the ski mountain descend the dramatically named Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the “blood of Christ” range, named for the words used by a Spanish explorer at the sight of the blood-red snowy peaks at sunrise. From the ski area summit you can look out at peaks and land owned and inhabited by one of the oldest cultures in North America, the Taos Pueblo people.

The Ski Valley, founded in the 1950s by Mickey Blake’s parents, Ernie and Rhoda Blake, who came West with the dream of starting a resort, owes its unquestionable mystique to its remote location and stunning high-desert scenery, the area’s artsy sophistication, a low-key, Southwestern vibe and the Blake family’s commitment to both tough adventure-style skiing and family-friendly instructor-led weeks.

The resort’s founders, Ernie and Rhoda Blake, created an area with low-key, Southwestern vibe. CreditKate Russell for The New York Times

But the mountain’s heyday was back in the 1990s, when skier visits peaked at about 350,000 a year. As the facilities aged, skiers drifted away. By the 2005-2006 season, annual skier numbers plummeted to fewer than 160,000. (By comparison, an average season at Telluride, Colo., easily crests 400,000). Locals loved the empty lift lines and untracked powder, but the business was dying.

So, when the financier and conservationist Louis Bacon purchased Taos Ski Valley from the Blakes five years ago, he set out both to turn the business around with $300 million in on-mountain and base-area investments, and win over undecided, possessive locals. Or, as Taos chief executive David Norden put it, “make this a sustainable business without messing with the magic.”

As part of that plan, the company undertook the rigorous process to become a certified B-Corporation — a designation that requires an annual third-party certification of social and environmental performance and public good — the first and only ski resort in North America to do so, joining the progressive, eco-friendly ranks of Ben & Jerry’s, Seventh Generation and Patagonia.

The snow swept in with a vengeance early this winter, and with four new lifts, a new hotel, a revamped base area and a spacious children’s center and ski school, among other recent investments, everything was coming together.

Then disaster struck.

On Jan. 17, two skiers were descending a chute off the flank of Kachina Peak — a steep, above-tree-line, experts-only zone within the area’s boundaries that had been opened for skiing — when an avalanche broke loose, burying them in tens of feet of snow. Members of the Taos ski patrol were on the scene instantly, organizing a search with hundreds of volunteers. Using probes and shovels, they found and extracted the victims from the frozen debris. But the two skiers, Corey Borg-Massanari, 22, who grew up in Minnesota and was living in Vail. Colo., and Matthew Zonghetti, 26, of Mansfield, Mass., both died after being taken to separate hospitals.

The powder was fresh and deep on the day in question, and before opening the steeps for skiing the Taos ski patrol had set off explosives throughout the upper mountain and specifically in the area that slid to test the snowpack’s stability and release dangerous snow layers should they be prone to avalanche.

The accident sent shock waves through the industry, where ski areas with avalanche-prone steeps make similar calls daily. Although avalanche accidents — and deaths — occur almost every season in the North American backcountry, they are uncommon inside resort areas where trained ski patrols carefully monitor and manage the snowpack.

A week before, I’d skied directly beneath the K3 chute where the avalanche would come down. Almost 30 years ago to the week, in January of 1989, a massive avalanche crashed down the face of Kachina in the same area. Mr. Blake, the mountain’s co-founder, had died that month, and Mother Nature responded a week later with a blizzard of biblical proportions, setting up dangerous avalanche conditions. “Ernie’s Storm,” as locals still refer to it, had led to the closure of much of the upper mountain, so that slide fortunately harmed no one.

The slopes of Kachina Peak had long been open only to those willing to hike up to the resort’s highest point, at 12,481 feet. A new chair up the peak was Mr. Bacon’s first investment. It opened in 2015, signaling the new owner’s commitment to adventure skiing and to the memory of Mr. Blake, who had long envisioned the lift. But the new chairlift was not without controversy. Some locals regarded Kachina as terrain too challenging for people unwilling to hoof it. Resort officials had no comment as to whether the men who died hiked to their starting point or rode the lift.

The inbounds, open-terrain avalanche deaths underscored a fundamental challenge for rugged ski mountains like the Taos Ski Valley: they are meccas for adventure skiing, which is inherently dangerous. We pray for deep snow, but on some slopes, under certain conditions it can kill. What is a resort’s risk tolerance; and what is ours?

A bright beginning

Until Jan 17, Taos Ski Valley operators had been focused on the modernization of the aging ski area. My visit in early January seemed perfectly timed.

To arrive at the slopes you ascend from arid, scrub desert into a tight canyon of tall pines, the snow along the road rising from a dusting to mountains of it. All of sudden, it’s deep winter.

I was greeted by fresh snowfall and buoyant Taos executives: they were celebrating a 20-percent jump in 2018-2019 season pass sales over the previous year, matching a three-year trend, and the holiday season had just delivered the strongest two weeks of business in Taos history.

Taos was undergoing a renaissance. The directive, Mr. Norden told me, was “change everything, but change nothing at all.”

The new ownership had set a deliberate pattern to its rollout of changes, focusing on families with children, lodging, food services and the quality of the skiing, both for experts and beginners.

After building the Kachina Chair, which closed after the avalanche but has now been reopened, children and families came next. In 2017 the ski valley opened a modern, spacious children’s center and ski school, and carefully carved out learning slopes served by two new lifts — a “gondolita,” as the short, easy-to-board child-friendly conveyance is called, and a chairlift.

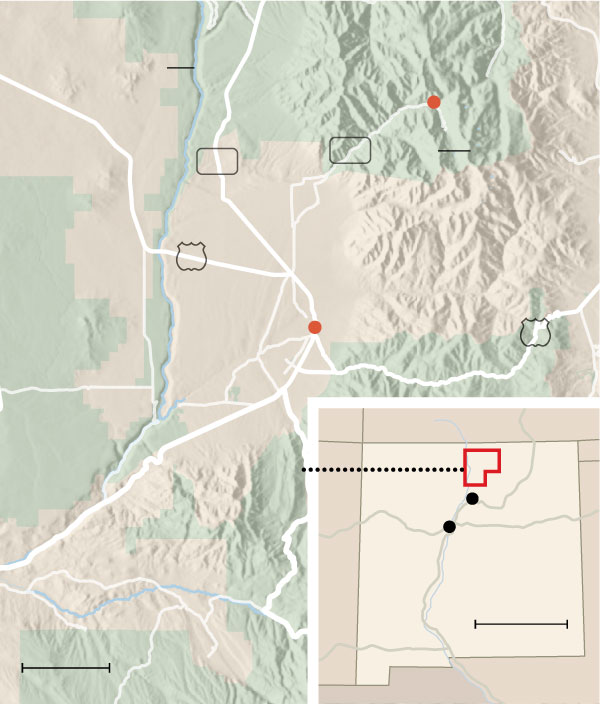

Just before Christmas, in a direct challenge to the area’s reputation for being remote and difficult to reach, Taos Ski Valley launched its own airline, Taos Air, which began offering scheduled flights from Austin and Dallas — Texas is Taos’s biggest market — to the small municipal airport. It is the only scheduled airline operating out of Taos. Everyone else either drives (12 hours from Dallas) or flies to Albuquerque (a three-hour drive) or to the smaller airport in Santa Fe (a 1.5-hour drive).

But the most visible symbol of change was the new luxury hotel at the resort’s base, The Blake, which opened in 2017. The 80-room structure — 65 rooms and 15 suites — looms huge over the base area, yet the scale inside, though luxuriously comfortable, is intimate, reminiscent of a cozy European alpine hotel. Its reverence for the history of the area is expressed by everything down to the art collection: two walls of Blake family photographs; a Georgia O’Keeffe over the reception desk; a haunting photographic study of American Indian tribes by the photographer Edward Curtis down another hall; and huge floor-to-ceiling historical ski photographs by Dick Durrance, known for his images of the outdoors, on every landing.

Around the ski valley, people seemed to feel that the new resort operators were trying hard not to upset the alluring, low-key vibe, but were unsure that it could be done.

I’d connected with Mr. Hahn, the patroller and something of a legend at the ski valley, through Mr. Norden, the mountain’s chief executive. A mountaineer and guide — Mr. Hahn has summited Everest 15 times, once as a guide for New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson — he returns every season to patrol at Taos. In the spring he guides at Mr. Bacon’s heli-ski operation in Alaska.

“I think all of us are hoping this investment and this new energy is a success,” Mr. Hahn told me as we traversed through familiar spruce glades at the foot of Walkyries Chute. “But we’re also hoping that nothing changes.”

“Funny,” he said, “I think Louis Bacon feels the same way.”

With Mr. Bacon’s purchase five years ago, the ski valley became another of the great American ski resorts to slip from the grasp of its founders. Unlike so many others being swept up — recent acquisitions include Stowe being bought by Vail Resorts, Deer Valley, Mammoth and Big Bear by Alterra Mountain Company, and Eldora by the Powdr Corp. — Taos was bought by a single owner who, by all accounts, loves the place. (Mr. Bacon declined to be interviewed for this article, instead answering questions via email).

Based primarily in New York, Mr. Bacon came to ski Taos in 1996, and like so many others, fell in love with the place. He bought land with the intention of developing it. But by the early 2000s Taos was falling behind.

There began a courtship with Mr. Bacon. The Blakes knew him. As a local landowner and an interested party, he’d worked with the family on a development plan to generate revenue for needed ski valley improvements. But as the costs became clear, the Blakes realized they didn’t have the money to make them happen. Mr. Bacon did, and the family sensed he’d do it their way.

“It was just so far beyond our means,” Mickey Blake explained recently. Mr. Bacon had earned their trust, he said, and shared their vision. “He’s headed in the direction we wanted to go.”

Mr. Bacon is undeniably a contrast in style to the founding family. He flies in for powder days, meetings with his on-site managers, and sunny lunches at the Bavarian, a charming mid-mountain alpine-style bar and restaurant established two decades ago and still run by, well, a Bavarian. The Blakes ran the ski valley hands-on for decades, and lived in an apartment overlooking the base area. Mickey Blake also lived nearby, with family members intimately involved in every aspect of the business.

Taos is just one of Mr. Bacon’s many investments and interests. He founded and runs the hedge fund Moore Capital Management and oversees an international real estate empire, including vast properties held for conservation

Of his plans for Taos, Mr. Bacon wrote in an email, “We are upgrading in ways that are both transformative and imperceptible.”

The decision to become a B corporation was, as Mr. Bacon said, both transformative and imperceptible. It had public relations upsides in both multicultural, eco-minded Taos and with the ski valley’s broader market. B-Corp status is earned through a rigorous annual review of a company’s social and environmental performance, transparency, community involvement, and charitable giving.

“It signals that we’re a purpose-driven company that is all about stewardship, stewardship of this place, of the people who work for us, of the Taos community, of the region, and the planet,” said Mr. Norden, a resort consultant brought in from Stowe where he helped oversee its $500 million transformation before its sale to Vail Resorts.

The Jan. 17 avalanche turned Mr. Norden’s singular focus to the accident and to the support of the victims and their families, his staff and customers, many of whom rushed to the avalanche site to help in the search.

In its wake, the company declined to discuss the details of the avalanche, pending the completion of an internal investigation. The National Forest Service is also investigating; the Taos Ski Valley operates under a permit in the Carson National Forest.

Fatal accidents at ski areas — particularly from inbound avalanches — are delicate, complicated terrain for all involved. Immense grief meets soul searching, “what-ifs,” and, in some cases, lawsuits.

When reached on the phone, Matthew Zonghetti’s father, Michael Zonghetti, had only praise for Taos Ski Valley staff and Mr. Norden. The father of Corey Borg-Massanari did not respond to a request for comment.

“One thing that surprised me is the support from the people at the mountain and the hospital,” Michael Zonghetti said two weeks after the accident, adding that a connection had developed between the family and Taos. “That connectedness is helping.”

Mr. Zonghetti invited Mr. Norden to Matthew’s funeral in Mansfield, Mass, a Boston suburb, and, afterward, to speak at a gathering of 200-300 family and friends.

Setting climate and social goals

Taos is the first and only ski area in North America to earn the B-Corp badge, but across the winter sports industry, leaders are starting to make climate change and carbon reduction a priority.

As part of its B-Corp commitment, Taos is on its way to meeting an ambitious goal to reduce its carbon footprint by 20 percent by next year, through investments in more efficient snow-making and grooming, an electric fleet, and the purchase of carbon offsets for its Taos Air flights. You’re unlikely to find a plastic water bottle in the Blake (they’ll furnish you with a reusable container), which is heated and cooled geo-thermally. Taos has set a starting wage at more than 30 percent the state minimum wage of $7.50 an hour, and the ski valley’s charitable arm has donated an average of a quarter-million dollars a year in cash, goods and services to local causes since 2015, resort officials said.

Guests don’t get hit over the head with all this, but apparently they like it. An online B-Corp announcement in February 2017 resulted in the most lift tickets ever sold in Taos history. “We actually got messages saying ‘we’ve decided on you guys because you’ve gone to B-Corp,’” said Dawn Boulware, who heads up the area’s B-Corp efforts.

B-Corporation has also been good for the skiing. In a partnership with the Nature Conservancy and the National Forest Service that was part of its B-Corp application, the ski area has been selectively trimming hundreds of acres of forest. The trimming improves the forest’s resiliency to fire, and in the process protects water quality and enhances raptor habitat.

But if you’re a skier or snowboarder what really matters is the thinning created the 1,900-vertical-foot Wild West Glade, some of the finest gladed skiing in the southwest.

Out in the Wild West one morning I’m trying to pay attention to Eddie Wisdom. We’re standing in the untracked glade that represents seven years of his life’s work. Mr. Wisdom, who is also on the Taos ski patrol, was the lead “sawyer” in trimming it out. He’s explaining every detail of why this is all a good thing for the trees, the birds and the water. I’m distracted. It’s the shin-deep powder amid the trees that have my attention.

Mr. Wisdom gives up, and we turn downhill. Like so much of Taos, his creation has character: the gaps between the spruce trees open and close for hundreds of yards, before spreading out into a steep 20-turn pitch, eventually throwing us out onto a sunlight groomer.

“You know,” he says, “that’s my favorite place in the world.”

A little later I sat outside in the surprisingly warm January sun at the new base-area plaza looking up at Al’s Run, the steep slope down the mountain’s frontside that is many people’s daunting introduction to Taos, and had a coffee. The Black Diamond espresso bar’s quirky playlist (Cesária Évora, Manu Chao, what sounded like Edith Piaf) was another of the many hints that as much as Taos was changing, it could still feel like the old days.

Biddle Duke is a writer and newspaper and magazine editor and publisher based in northern Vermont.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.