Concealed behind the pasty mask, the trademark fright wig and the impassive expression Andy Warhol showed to the world was a man of roiling complexities. Depending on who does the talking, Warhol was either an emotional vampire draining vital juices from the animated nut-jobs he gathered to him or a kindly, if slightly creepy, avuncular figure whose motives have been misunderstood.

He drew them to him — a recessive dynamo at the center of a dysfunctional hive — first at the raw Silver Factory on East 47th Street in Manhattan (for which he paid rent of $100 a year); afterward at the more polished headquarters of his varied ventures on Union Square West; and, finally, at a refitted power station in the East 30s.

Leave it to the critics to pronounce on the vast oeuvre when a major Warhol retrospective — the paintings, the films, the time capsules — opens amid a flurry of parties on Nov. 12 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

What comes clear in interviews with more than two dozen former friends and colleagues from the various Factory spaces is that, from the start of a career that ended with his premature death at 58, the rabidly ambitious and deeply needy Warhol marshaled all that was paradoxical in his nature and put it to the service of the sustained piece of performance art that was his public self.

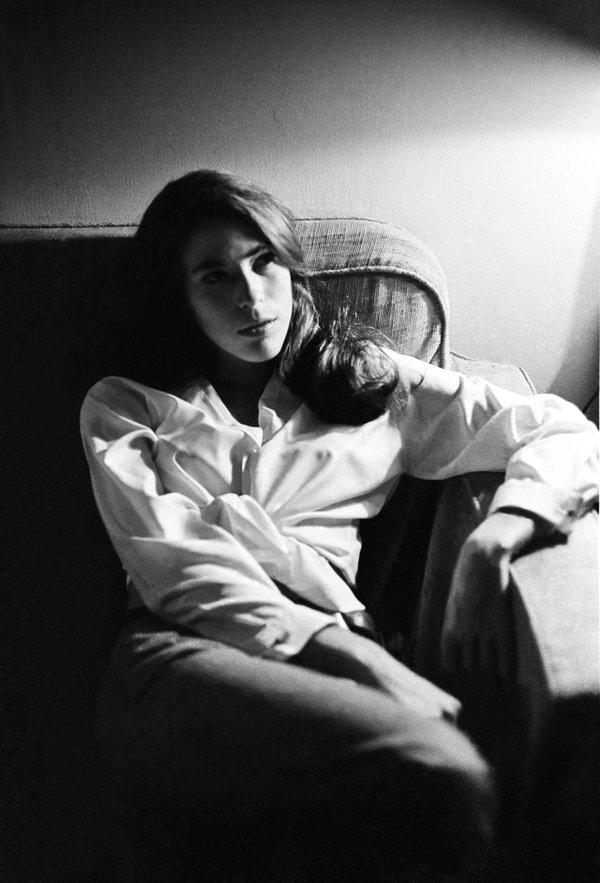

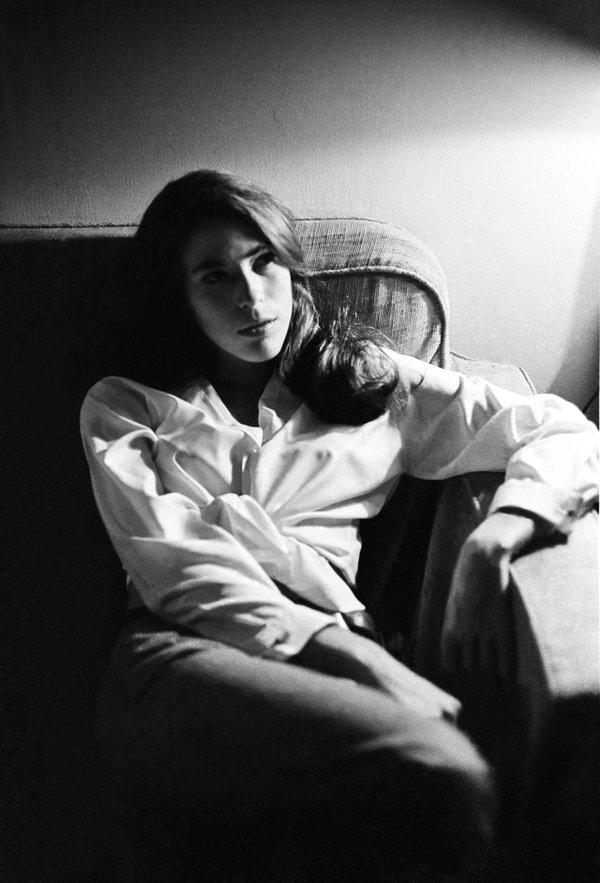

Mary Woronov, who starred in “Chelsea Girls,” in 1966.CreditSanti Visalli/Getty Images

‘It was so dark that you couldn’t see any art.’

Fran Lebowitz, 68, writer. Factory years: 1970s.

When you walked in, there was a metal door. After that door opened, there was another metal door. On it, handwritten on a piece of paper torn from a legal pad, was a note that read, “Knock loudly and announce yourself.” I knocked, and someone said, “Who’s there?” I said, “Valerie Solanas” [Warhol’s would-be assassin]. And Andy opened the door.

Mary Woronov, 74, painter, writer, actress. Factory years: 1960s.

The place seemed dirty. There were several drag queens limping around. They limped because they wanted to shock you. They really didn’t like you, and their recourse was to limp.

It was so dark that you couldn’t see any art. The place had silver foil all over it.

André Leon Talley, 69, fashion journalist. Receptionist at the Union Square Factory, 1975.

The Factory was very much a creative playpen, but there were still rules. You had to show up every day, or you would be fired. Andy was always walking around being very vague about everything. But you had to be enthusiastic. There was a seriousness about the place, a decorum and deportment.

I typed on a manual typewriter that was spray-painted gold. I wish I’d kept that. There was a Jean Dupas silk-screen poster from the Normandie. I had that behind my desk.

Andre Leon Talley, 1975, Providence, RI.Creditvia Bobby Grossman Archives

That was the Interview side. In a space behind us, people were typing on these big IBM Selectric typewriters, transcribing tapes. Andy would paint behind the offices in the back. You weren’t supposed to go back there, but I would spend hours watching him doing the silk screens on the floor. The colors would be mixed for him. He would apply them with rollers. It was a process. That’s why he called the place the Factory.

‘A medieval court of lunatics.’

Fran Lebowitz

When I first went to the Factory, there was an interesting group of young people. Andy always had some rich kids around him but also people who were incredibly flamboyant, incredibly transgressive. They were there for his amusement. Later, Andy could not distinguish between an interesting young person and just a young person.

Benedetta Barzini, 75, Vogue model, actress. Factory years: 1960s.

Many of the people around Andy were the sons and daughters of the wealthy bourgeois collectors of his works — these abandoned people. Edie Sedgwick is a good example, but there were others.

The model Benedetta Barzini in 1970.CreditFranco Rubartelli/Conde Nast, via Getty Images

Mary Woronov

These people were nuts They were doing high-grade amphetamines. Ondine [Robert Olivo, actor] was taking my mother’s Eskatrol. They did drugs all the time.

Fran Lebowitz

Andy encouraged bad behavior by people who were already unstable. I noticed a very high mortality rate of people near him.

Mary Woronov

One day a drug dealer came up. He shot up this girl, and she for some reason passed out. It was in the bathtub. She went under water. We thought she was dead. We panicked because she was not waking up. Finally someone said, “We should send her down the mail chute.” We wrote little notes on her body and puts stamps on her forehead. Then we realized she wasn’t dead. I don’t think she would have fit in the mail chute. But we would have tried.

In those days the Factory was like a medieval court of lunatics. You pledged allegiance to the king — King Warhol. Yet there was oddly no hierarchy. Warhol was also one of us. He accepted the responsibility. He accepted the insanity.

‘It really wasn’t a party until you ran into Andy.’

Fran Lebowitz

The atmosphere around Andy was always very competitive. There were people who wanted to be in this entourage Andy had, people who wanted Andy to bring them places.

Liz Derringer, 68, music journalist. Factory years: 1968-87.

It really wasn’t a party until you ran into Andy. Andrea Feldman [actress] brought me up to the original Factory. One night she said, “We’re going with Andy to the opening of a new nightclub.” It was called Salvation. It was on Sheridan Square. They picked us up in a limo, and I was so impressed to be sitting with Andy Warhol. My sister had made a dress for me out of three triangles. My skirt was way above my knees. When we got there, they put all these fake tattoos between my breasts and led us to the V.I.P. section, so I was really high on myself.

Joe Dallesandro in 1971.CreditJack Robinson/Conde Nast, via Getty Images

Bebe Buell, 65, singer, model. Factory years: early to mid-1970s.

Andy took an immediate interest in all new, fresh faces that came through the scene. He didn’t talk much. He laughed a lot. He would ask questions. It was: “Where did you get that dress?” “Oh, who did your makeup?” “Who’s that beautiful boy you’re with?”

Joe Dallesandro, 69, actor. Factory years: 1960s.

My friend said, “Let’s go over and meet the Campbell’s soup guy.” I thought it was the Campbell’s soup you eat. Warhol was an artist, but I was too young to know any of that. I was 18. When I first met him, he was sitting behind the camera reading the newspaper. When somebody laughed or did something interesting, you’d see this hand come out from behind the newspaper and turn the camera on.

David Croland, 71, model, actor, illustrator. Factory years: 1965-68.

Fashion and the art world hadn’t quite collided yet. Andy pushed it forward in a way no one had. Andy loved Halston. Halston loved Andy. There was Valentino and Giancarlo Giammetti. There was Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. They would all come to New York for the season, and we would hang about together and go to Joe Eula’s house — Andy and his group, Joe and his group, Halston and his group. We were all in the same room. Marisa and Berry Berenson, Loulou de la Falaise, Elsa Peretti all socialized together.

Danny Fields, 78, music industry executive, former manager of the Ramones. Factory years: 1960s.

We all went to the San Remo in those days. That was the genesis of the first Factory. It was a bar at Bleecker and Macdougal, a tile floor place with an Italian matriarch who’d inherited it. Somehow it turned into the gay bohemian bar of the early 1960s. Andy was there with Ondine and Billy Name. Terence McNally was there with his boyfriend, Edward Albee. The Rauschenbergs and the Jaspers were there. It was watched over by this large, stern woman, like the woman in “8 1/2.” She would walk by pleased but saying: “Don’t you boys start behaving like faggots. Just behave. Don’t scream.”

David Croland

Andy was a great teacher. He taught me to always get a corner table in a restaurant, where you could see and be seen. People really looked at each other in those days. They didn’t have cellphones. The entertainment was you.

David Croland at his studio in New York City, 1974.CreditRon Galella/WireImage, via Getty Images

Liz Derringer

I think he enjoyed the circus. He enjoyed being the ringleader.

‘He was a vampire.’

Bob Colacello, 71, writer, social chronicler, former Interview editor. Factory years: 1971-83.

We all could do something that Andy could not do. He loved the fact that I had a very good memory for what people said. He told me, “Oh, gee, if people won’t let me tape-record, you could be my human tape recorder.” He got other people involved so that no one person would get too much credit.

Viva (Susan Hoffman), 80, writer, actress. Factory years: 1960s.

Andy could make you feel special. He used to say to me, “Oh, Viva, your mind is a gold mine.” Of course he totally depended on other people for his stuff.

Fran Lebowitz

He didn’t talk, Andy. What he wanted to do was get you to talk. He was a vampire. He wanted to take things from people. I could talk. That’s what he could take from me.

Sam Bolton, left, and Jeffrey Slonim at the Factory in 1986.CreditPatrick McMullan/Getty Images

Sam Bolton, 53, former executive assistant to Fred Hughes. Factory years: 1980s.

My job was to set up the appointments for the portraits, the luncheons, the meetings. Sometimes I’d set up lunch in the dining room for advertisers or a person getting a portrait. That was my main job. But then sometimes you’d shift around. Sometimes I’d help with the Polaroids for the portraits. People say, “Oh, you painted Andy’s pictures.” But we never did more than fill in the backgrounds.

Viva

I went with Andy on a series of college lecture tours, and my role was to do the talking for him. He wouldn’t talk. Maybe he was dyslexic. Andy didn’t have social skills, let’s put it that way. But he ended up making a virtue of that by being so mysterious, which was really brilliant, turning his liabilities into a mystery, which made him very sought-after because everybody else is just the opposite.

‘He chased you and then he moved on.’

Benedetta Barzini

There was also this about the Factory: There were all these people hanging around hoping to find themselves but losing themselves more and more and more. I think Andy enjoyed seeing the suffering.

Andy Warhol and Lou Reed with Danny Fields at a David Johansen show at the Bottom Line in 1978.CreditEbet Roberts/Getty Images

Danny Fields

There was a time when we went to Peter Knoll’s [heir to the Knoll furniture fortune] apartment on East 72nd Street. Andy was sitting on a sofa while Ivy Nicholson [model and actress] was disgracing herself, crawling around on her hands and knees bemoaning her love for Andy. Every so often Andy would, not violently but with a slight lift of his foot, kick her like a tiresome child or a dog you did not want to hurt but wanted to go away.

Dustin Pittman, photographer. Factory years: 1969-75.

He chased you and then — there is no gentle way to say this — he moved on. When Andy dropped the Superstars, they were upset. They all expected Andy to take care of them. They felt they certainly had a part in Andy’s fame.

Geraldine Smith, 69, actress. Factory years: 1960s.

He liked people that he thought had star quality. He put you in his movies, and then it was up to you to parlay that into something else. A lot of people didn’t.

Dustin Pittman, 1984.CreditGerard Malanga

‘We have to bring home the bacon.’

Bob Colacello

There was a striking contrast between the Silver Factory of the 1960s and the Union Square Factory. Before the shooting [1968], Andy hired rebellious heiresses like Edie, Brigid [Berlin] or street kids.

Once Andy was shot, all that stopped. He weeded out many of the society kids, the amphetamine addicts and even gradually the drag queens. In the past there wasn’t really a strong bourgeois element. But from the early ’70s, and by the time we moved to Broadway, pretty much everyone he hired came out of college, from upper-middle-class families. Andy turned the Factory into a real business. There was health insurance. When I left, we had money in a pension plan.

Bebe Buell

He was looking for people to buy his paintings. He was the ultimate salesman, Mr. Andy. I told him I came from Virginia, and the first thing he said to me was that I looked like I came from a family of horse breeders. He was looking to see if I came from any kind of money.

Viva

We went out every night to Max’s and then, if it was happening, to the gathering of some rich person who might buy Andy’s art. Andy always said: “Oh, we have to go to this party. We have to bring home the bacon.”

Bob Colacello

Fred [Hughes] was social director. I was the assistant social director, organizing lunches for Interview. We would lure people, telling them we were unveiling the Marella Agnelli portrait, or the Mick Jagger. They would get the idea that they should get their portraits done, too, and they would come. It was always a soft sell.

Paige Powell at Limelight in New York City, 1984.CreditPatrick McMullan/Getty Images

Paige Powell, 67, artist, photographer, former advertising director of Interview. Factory years: 1980s.

My previous job had been as the public affairs director of the Portland Zoo, where I sold packaged elephant manure called Patsy’s Garden Elixir. We also sold it by the can as Zoo Do. I guess at the Factory they figured, if she can sell elephant manure, she can probably sell ads in Interview.

Vincent Fremont, 67, curator and art adviser; former vice president, Andy Warhol Enterprises. Factory years: 1969-87.

At the close of every year, Andy was very nervous and would say, “This is the end.” He had this anxiety because he came from a poor background. He didn’t have any credit cards. He didn’t want his name on his checks. He felt someone could take one of his checks, run to the bank and steal his money.

Dustin Pittman

But Andy could be generous. He’d always say, “Why don’t you go in the back and take a painting.” In the late ’60s, those paintings were, like, $300. Andy used to try to pay his Superstars, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn and others, with paintings. But they didn’t really want the paintings, they wanted cash.

‘It was never about money. It was always boys, clothes and sex.’

Corey Grant Tippin, 68, model, antiquarian’s agent. Factory years; 1967-74.

It was not the idea that we were going to be rich. We just wanted attention. We used to make lists of what were the most important things, and it was never about money. It was always boys, clothes and sex.

Corey Tippin in 1971.CreditJack Mitchell/Getty Images

Robert Heide, 79, playwright. Factory years: 1960s.

People have said that Andy was asexual. Not so. When I first knew him, he was having a little affair with Edward Wallowitch, the photographer. Ed was a protégé of Edward Steichen, and he had photographs in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art at a really early age. Edward also took pictures for newspapers, so a lot of the photos Andy used were Edward’s.

There was a famous one of women eating tuna out of a can, and they’d been poisoned by the can [“Tunafish Disaster,” 1963]. Andy decided to do a big silk screen of that. I remember him giggling about the deaths.

Sam Bolton

He had this strange relationship with Jon Gould [Paramount executive]. Everyone projects it as some huge love affair, but all I ever heard about was how horribly he treated Andy. I don’t think he was the love of Andy’s life. Jed Johnson [decorator] was.

Bob Colacello

After Andy was shot, Paul Morrissey [filmmaker, Warhol collaborator] said, “Jed, you should move into Andy’s house and help Julia [Warhola, Warhol’s mother] take care of Andy.” It turned into one of those classic patient-and-nurse-fall-in-love things. Andy adored Jed, but he had a hard time showing his affection. That bothered Jed. I sometimes would say to Andy, “Maybe if you showed a little more feeling toward Jed. …” Andy told me, “Bob, if I had feelings, I would have a nervous breakdown.”

He used to say, “I want to be a machine.” He kind of meant it. He was always trying to figure out human relationships.

‘The world’s most sophisticated child.’

Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni, 55, journalist. Factory year: 1987.

I was expecting Andy, because of his fame, to be pretentious, but he was actually quite funny and catty. He realized that as a 16-year-old out of convent school, I knew nothing about art. That amused him. In a way he was very sensitive and amoeba-like.

Cornelia Guest, 54, actress, animal rights activist. Factory years: 1980s.

Andy came to my parents’ house for dinner when I was 5 years old. I had a new Jack Russell terrier, and Andy said, “I’d love to come upstairs and see it.” He came and we sat on the floor and played with the puppy for so long that Mother eventually sent people up to say, “Mr. Warhol, dinner is ready.” And he was, like, “Can’t I have dinner with Cornelia?” He was like a big brother, really.

Cornelia Guest, Halston and Andy Warhol.CreditRon Galella/WireImage, via Getty Images

David Croland

If someone hurt his feelings, which they did a lot, Andy would turn very quietly to one of us and say, “Oh, who does he think he is?” It was in a hurt kind of way, not in a contentious way. He’d ask, “Why would he say something so rude to my face like that?”

Bob Colacello

He was always trying to make sense of things. He was always asking why. He could be very funny, like a child, the world’s most sophisticated child — and jaded child. He was like the kid who could walk into a room, all innocence, and ask, “Mommy, what’s that spot on the floor,” and then point to that spot where the dog just peed. When you told him any two people were getting married, he’d say, “Which one has the money?” You’d tell him: “No, Andy, it’s not about the money. They’re in love.” He would turn to me and ask, “You believe in love, Bob?”

‘He wanted to be No. 1.’

Robert Heide

He was, as people say, very shy, very reticent. And yet there was a passive-aggressive aspect, an ambition.

Robert Heide, left, on the set of “Batman Dracula.”CreditBilly Name

Dustin Pittman

Andy wanted to move up the ladder. Within the art world, people respected him but still had their doubts. He loved society, Hollywood, wealth, opulence — all that stuff.

Bob Colacello

We used to tease Andy, “You could run for president.” He liked hearing that. He was unbelievably ambitious. But he hid it very well. He’d say, offhandedly, “Oh, I’m just painting society portraits.” But in fact he wanted to be No. 1, to have an important position in the history of art. He went into Pop Art because he saw that Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein started to get all that attention.

He became friendly with Paloma Picasso. Andy would grill her: “How many paintings a day did your father do?” “How long did each painting take?” “Where did he get his ideas?” He wanted that kind of fame.