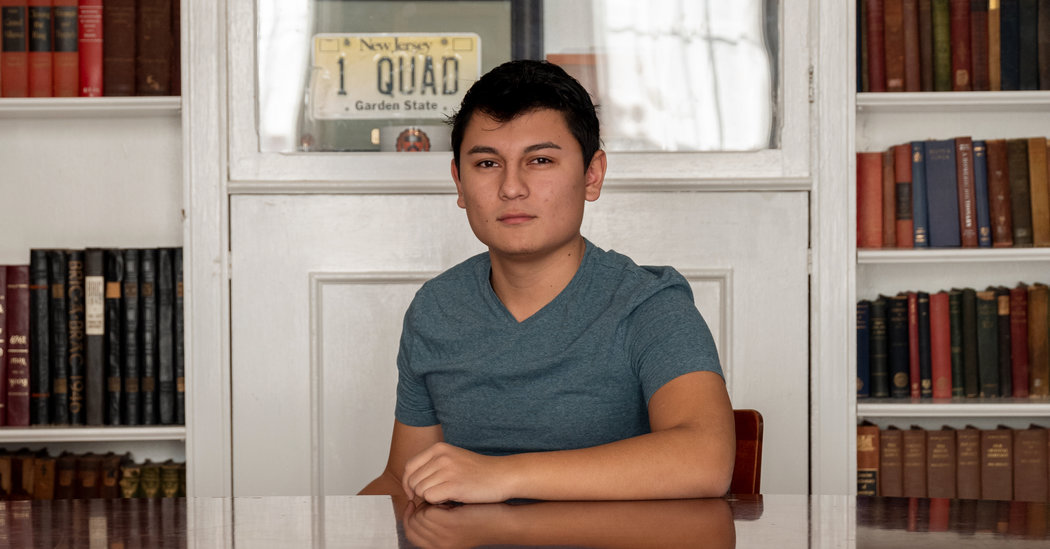

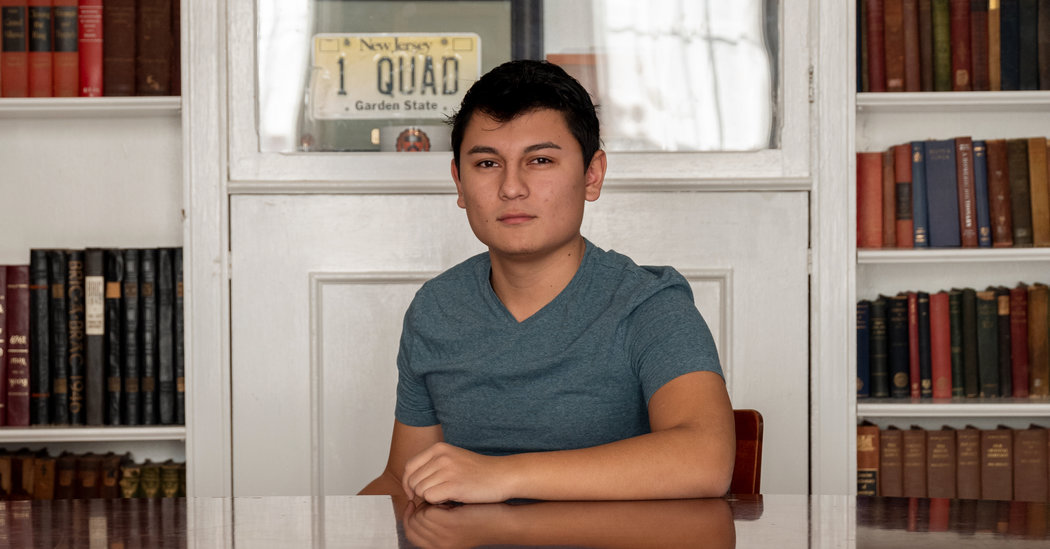

In the fall of 2017, when Daniel Pallares Bello was a sophomore at Princeton, a friend invited him to visit Quadrangle, a stately mansion on Prospect Avenue across from campus that houses a student eating club.

But unlike many undergraduates excited to take part in the more than century-old tradition of eating and socializing in the wood-paneled refectories and felted billiard rooms of Fitzgeraldian fame, Mr. Pallares was conflicted.

“The first thing I was told by low-income upperclassmen was that they weren’t a place for us,” said Mr. Pallares, now 22, a first-generation college student on full scholarship. “They’re too expensive, they’re not for Latino people like me, it wouldn’t be a friendly environment.”

Quadrangle is one of the smallest of the 11 eating-club houses on “the Street,” as students call it, though there is still a video game room with seven gaming systems, a billiard room with two pool tables, a solarium where students play board games, a TV room with a 60-inch screen, ample nooks for chatting or studying, a pub alcove with high-top tables and a 200-person dining room that offers made-to-order meals and fancy soda and espresso machines.

Mr. Pallares was impressed. He was also surprised by how welcoming the club was. He decided to join, using summer job earnings to cover the initial $600 fee. But he didn’t tell his mother, a county clerk, or his father, a landscaper, who live in The Woodlands, Texas.

“They may wonder how this is justified, and I didn’t have a good answer,” he said.

Mr. Pallares wanted to give them one. He campaigned for club president on a platform of inclusivity and was elected. Then he started recruiting his first-generation and low-income peers, whose increasing visibility and volubility across the country has engendered the acronym FLI.

Quadrangle is one of five “sign-in” eating clubs, which have no vetting process and allow friends to join in groups. (The other six — selective “bicker” clubs — require students to undergo an interview process.)

Mr. Pallares made Quadrangle membership attractive by emphasizing its welcoming, homey atmosphere and helping FLI sophomores cut down on fees by tweaking their university meal plans. He then approached the club’s board of trustees about covering dues for scholarship students.

After months of negotiations he prevailed, and Quadrangle now has the highest percentage of FLI students on the Street, including the newly inaugurated president and one of two new social chairs.

“We can see the writing on the wall,” said Dinesh Maneyapanda, the chairman of Quadrangle’s board of trustees. “The demographics of Princeton are changing, and my responsibility is to make sure the club can persist for the next 100 years.”

Opening Doors

Between 68 and 72 percent of Princeton upperclassmen belong to an eating club each year, but FLI students don’t join in similar numbers. Many of these students receive full scholarships and tend to view the eating clubs as exclusionary: a representation of the Ivy League’s “Canada Goose culture” of privilege and extreme wealth.

It’s a perception that may be overblown in some instances, but is also based on real economic and social barriers to access.

Princeton is still overwhelmingly affluent. The estimated median family income for the class of 2023 is $173,800. But that number used to be a lot higher: $228,100 for the class of 2014.

The college is attracting many more FLI students than in previous decades. Seven percent of the class of 2008 were eligible for a Federal Pell grant, awarded to students of exceptional financial need; now 25 percent of the class of 2023 receive a Pell grant and identify as FLI.

Each year, close to 200 incoming FLI freshmen participate in on-campus or online programming, helping them acclimate to life in the Ivy League. Many of these students are invited to participate in a four-year mentoring program, in which they serve as leaders and social organizers.

Khristina Gonzalez, the associate dean and director of programs for access and inclusion at Princeton, said FLI students are highly active in student organizations and student government there.

“There’s a lot of pride around FLI identity: shirts and swag and bags and stickers,” Ms. Gonzalez said. “I work on the ground with students every day and there is so much joy in their lives in how they’re working to shift campus and grappling with the negative culture of wealth.”

FLI students can feel class divisions deeply. The summer before her junior year, Emerson Thomas, a low-income computer science major from Kennesaw, Ga., served as a freshman orientation leader.

When her group first met, “they were talking about their summers and where they’d been, and I as a leader felt kind of uncomfortable because I had nothing to add,” said Ms. Thomas, 21. “Even just going on a vacation is not an option for me.”

Touring colleges her senior year of high school, she remembers thinking, “the only reason I’m supposed to be here is if I have a broom.”

She just ended a year as Quadrangle’s vice president and is still considering all the implications of belonging there. “It’s definitely elitist: paying for someone to clean up after you, make your meals — I know the people who empty the trash can,” she said. “I’m always internally justifying the decision, especially talking to my family. But I want to be part of the effort to make eating clubs more inclusive.”

Princeton went no-loan in 2001, covering tuition, room and board based on its assessment of each family’s need.

The eating clubs, which aren’t part of the university, don’t operate this way. A full university meal plan costs about $7,060, while eating clubs cost $8,675 to $9,950 annually for juniors and seniors, and $600 to $1,300 for second-semester sophomores, who get limited meals.

In the past, most clubs offered scholarships or financial aid, “typically when a member who has signed in or joined has a change in financial circumstances,” said Hap Cooper, who is the president of the board of governors of Tiger Inn, a selective club, and the newly elected chairman of the Graduate Interclub Council, which links the clubs’s 11 boards.

Though the eating clubs technically aren’t part of Princeton, the university acknowledges how integral they are in students’ social lives, and so it tried to make them more accessible to scholarship recipients.

In 2007, the university started giving upperclassmen on scholarship a $2,000 bump in their board plans, in the hope that it would equalize club access. It didn’t quite work. The money offset costs for some eating clubs, but others charged hundreds more than the allotment.

And the aid was only for upperclassmen, despite the fact that most students join in their sophomore year. Today, many FLI students say they prefer to stay on the university’s lower-cost meal plan and then devote the extra money to books, travel home and family bills.

Mr. Cooper said that many clubs and their graduate boards are “vociferously and stridently pro-aid.” Some have started fund-raising and even creating scholarship endowments.

In 2017, a selective club called Cottage created a foundation for this purpose. Tiger Inn is currently fund-raising toward a $500,000 scholarship endowment. At least four selective clubs will soon cover fees for second-semester sophomores on aid.

Terrace, a sign-in club that was both the first to drop selective admissions and to admit women, now covers all fees for students on full scholarship, has a sliding scale for others and offers grants for incidentals. Roughly a third of the club’s members receive financial aid.

In the past, Quadrangle offered limited aid to rising seniors in financial straits. More recently, the board of trustees tried to implement a more generous policy but couldn’t make the numbers work. Then Mr. Pallares arrived.

“He made it his mission,” Mr. Maneyapanda said. But the clubs, especially the selective ones, are going to need more than aid if they’re serious about diversifying.

“There’s a lot to be said for role models, peers having these officer positions and generally being in the clubs,” Mr. Maneyapanda said. “If none of your friends join clubs and no one you know has joined a club, you think, ‘There’s no way I can join, nor would I want to.’”

Liam O’Connor, a senior who has reported extensively on eating clubs for The Daily Princetonian and analyzed club demographics, said scholarships may get more middle and low-income students to bicker the selective clubs.

“But whether it allows them to succeed and get in, I’m unsure of,” he said. He echoed the sentiments of other student skeptics: Selective clubs have biases, which often cut along socioeconomic lines.

Some students have occasionally advocated ending the bicker system and even the clubs themselves. Samuel Aftel, 21, came to this conclusion after he was “hosed” — rejected — twice from the selective Cap and Gown club.

He acknowledged that he had “significant personal bias” against the system. But he also said that if the rejection hurt him — white, privileged — it would probably feel even worse to minority students.

“The eating club system de facto segregates,” Mr. Aftel said. “And this country has a long dark history of using dining as a social sorting system.”

A Seat at the Table

Still, a number of FLI students at Quadrangle said they didn’t understand how important an eating club community could be until they joined.

“We have these great conversations on the Grand Salon couches,” said Krystal Delnoce, 20, the new president of Quadrangle. “Everyone is here bonding, especially late at night. There’s a sense of solidarity.”

She knew she could save money by taking the university aid home. But she decided the sacrifice was worth improving her quality of life on campus. “That’s increased tenfold,” she said.

Yet deciding to enter the club system can be fraught for FLI students, because they think differently about the relationship between money, power and privilege than others.

A spirit of noblesse oblige from the old guard doesn’t always translate. Mr. Cooper said that any second-semester sophomore who wanted to join Tiger Inn and didn’t have the funds, need simply ask. “It could be $250, could be $500. It’s usually not a showstopper,” he said. “And if folks come to us and say ‘Jeez, we weren’t budgeting this and need help,’ we help.”

But FLI students say these sums aren’t trivial, and that it can be highly uncomfortable, if not humiliating, to ask the very people judging one’s compatibility with club culture for money.

The university is trying to help students better understand class difference. For the first time, all freshmen this year were required to attend a panel featuring alumni from four different socioeconomic backgrounds.

“It was the most frank discussion of navigating privilege and wealth on campus that I’ve seen ever,” Ms. Gonzalez said. She believes attitudes are changing; legacy admissions has become a complicated topic on this campus, and elsewhere.

Princeton has long prided itself on preppy family tradition even as other Ivy League schools went more overtly meritocratic. But now even there some legacy students are reluctant to admit that their parents attended the school.

This has caused some defensiveness among some alumni and administrators. In February, Christopher L. Eisgruber, the president of Princeton, gave the welcome speech at the 1vyG conference, an annual event for FLI students at elite schools.

“Every student on every highly selective college campus is there because of merit, and you have something to learn from them,” he told the few hundred scholarship students sitting in University Chapel. They were misguided if they believed they had gotten in “by overcoming hardship and by tenacity,” while legacy students or affluent students got in “because of parents.”

Less than a month later the so-called Varsity Blues college admissions scandal broke. But even before that, students were upset.

“Saying we’re not different from everyone else on campus was undermining what an FLI identity is, and how hard we’ve worked to be here and the value we bring,” said Sarah Elkordy, 20, a Quadrangle member who helped organize the conference.

Others wondered why they had received a lecture, especially since the university wasn’t telling members of the most exclusive eating clubs how much they could learn from FLI students.

Ben Chang, a university spokesman, wrote in an email that “President Eisgruber is proud of every student on our campus, and believes that they all contribute to what makes Princeton unique.”

The president, he continued, has been “the driving force behind our significant efforts and substantial investments to attract and support talented first-gen and low-income students at Princeton.”

Ms. Gonzalez said that for all the progress Princeton and its adjacent institutions have made, “we are still working through structures of power” and “200 years of our country doing things a certain way.”

For a very long time, the clubs did not admit women (the last two holdouts, Ivy and Tiger Inn, were compelled by court order in 1990), and were less than welcoming to racial and ethnic minorities.

Mr. Cooper said that is different now: “When someone from some other demographic or an FLI student joins Tiger Inn, they find the place is chill, and not judgmental and not elitist.” The challenge, he said, “is getting them to come, consider the place and give it a chance.”

On a Friday in November, dozens of Quadrangle members gathered for a “make your own pizza” lunch in the basement dining room. They were a mix of scholarship students, legacies and others, some of them, including Ms. Thomas, wearing Quadrangle sweatshirts.

They chatted about the upcoming Casino Night party and their Thanksgiving plans. At one of the circular tables, about 10 students had gathered, though every few minutes, someone new wanted to squeeze in, forcing everyone to shift. It was the club’s motto, “there’s always room at a Quad table,” on display in real time.

“We bring people together beyond their financial circumstances,” Mr. Pallares said. “A lot of times at Princeton, your financial background defines how you behave and the opinions you hold in class, and that sometimes divides groups. But that doesn’t necessarily happen at Quad.”