WASHINGTON — The future of a commonly used abortion pill is at the center of a pitched legal battle before the Supreme Court, which is poised for the second time in a year to consider a major effort to severely limit access to abortion.

The court is expected to decide by Friday night whether to grant the Biden administration’s emergency request to maintain the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the pill, mifepristone, after a lower court limited the availability of the drug while an appeal moves forward.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. had paused the lower court’s ruling, but that freeze is set to expire at midnight. That means the justices are likely to decide before then, although they could extend the deadline or fail to act.

When the justices overturned Roe v. Wade in June, the conservative majority said that the political branch, not the courts, should make decisions on abortion policy. But the issue has quickly made its way back to the Supreme Court, in a case that may have wide-ranging consequences even in states where abortion is legal, as well as for the F.D.A.’s regulatory authority over other drugs.

Here’s what could happen next.

What’s at stake?

At issue is the availability of mifepristone, part of a two-drug regimen that now accounts for more than half of the abortions in the United States. More than five million women have used mifepristone to terminate their pregnancies in the United States, and dozens of other countries have approved the drug for use.

Federal judges have questioned steps the F.D.A. has taken to expand the drug’s distribution, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, imposed significant barriers to access last week, even as it said that it would allow the pill to remain on the market.

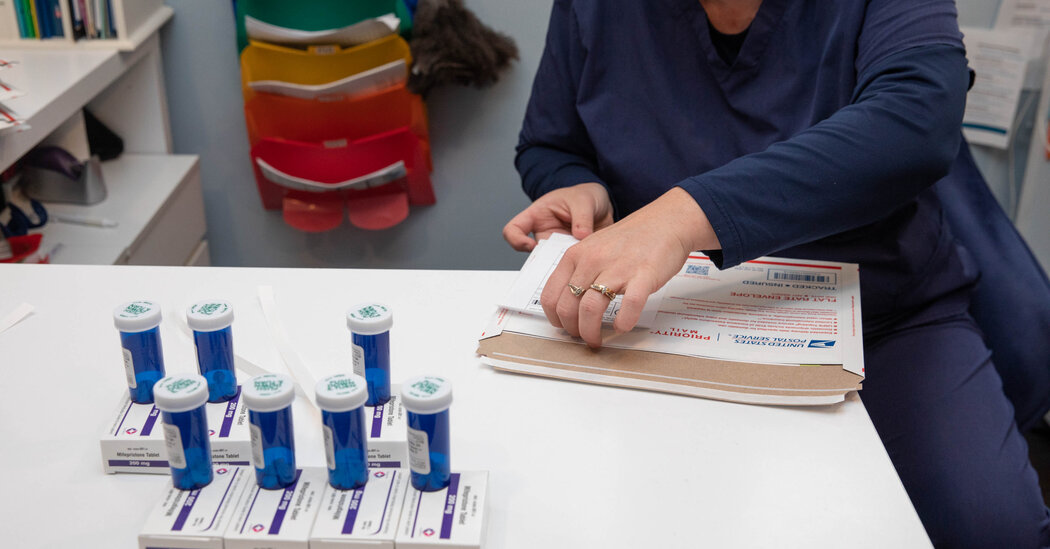

Its decision essentially turns back the clock to 2016, when the F.D.A. added a series of guidelines that eased access to the pill. The restrictions would include blocking patients from receiving the drug by mail.

Experts say removing the mail option would have significant consequences: Patients would have to take time off work, pay travel costs to get to a medical office and endure the stigma of going out in public to seek an abortion.

The case could also pave the way for all sorts of challenges to the F.D.A.’s approval of medications. Legal experts said medical providers anywhere in the country might be enabled to challenge government policy that might affect a patient, as did the anti-abortion medical coalition that filed the original lawsuit against the pill.

What happens next?

When the Biden administration asked the Supreme Court to intervene, the application was assigned to Justice Alito, who oversees the Fifth Circuit. Justice Alito issued an order last Friday temporarily ensuring that the pill would remain widely available. The order was extended on Wednesday for another two days.

That the court said Wednesday that it would give itself more time to consider the pill’s availability suggests that there may be disagreement among the justices.

The justices are likely to decide whether to grant the administration’s request and have several options: ensure full access to mifepristone; impose significant restrictions, but stop short of sharply curtailing the drug’s availability; or suspend the pill from the market entirely, as a federal judge in Texas did in the original case.

Whatever the justices do in the interim, the litigation will continue, probably in the appeals court. But the Supreme Court may take the unusual step of leapfrogging the appeals court and hearing the case itself right away.

If the Supreme Court decides not to act on the Biden administration’s request, the Fifth Circuit’s decision remains in place.

How did we get here?

The dispute traces back to a lawsuit by an umbrella group of medical organizations and a few doctors who oppose abortion, challenging the F.D.A.’s approval of the pill more than two decades ago.

The suit, filed in the Amarillo division of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, came before a single federal judge: Matthew J. Kacsmaryk, a Trump appointee who is known as a longtime opponent of abortion.

The plaintiffs have claimed that the pill is unsafe and that the agency’s approval process for the drug was flawed. The F.D.A. has forcefully countered those claims, contending that the drug is very safe and effective. It has cited a series of studies that show that serious complications are unusual and that less than 1 percent of patients need hospitalization.

In his preliminary ruling, Judge Kacsmaryk said that the Food and Drug Administration had improperly approved the drug. But he gave the agency a week to seek emergency relief before his ruling would take effect.

The Biden administration immediately appealed, and a divided three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit said that mifepristone could remain available as the lawsuit makes its way through the courts.

But in addition to prohibiting sending the pills by mail, the panel blocked health care providers who are not doctors from prescribing them.

What about the Washington State case?

A second case about the abortion pill is proceeding in a federal courtroom in Washington State, after Democratic attorneys general of 17 states and the District of Columbia filed a lawsuit challenging the renewed F.D.A. restrictions on access to mifepristone.

Less than an hour after Judge Kacsmaryk issued his ruling, Judge Thomas O. Rice of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Washington, an Obama appointee, blocked the agency from curbing the availability of mifepristone in those 17 states and the District of Columbia. Although his order did not affect the entire country, the states in that lawsuit represent a majority of states where abortion remains legal.

Legal experts say the direct conflict between the Washington State case and the Fifth Circuit’s decision to block specific parts of the F.D.A.’s rules for the abortion drug potentially increases the chances the Supreme Court will quickly address the merits of the dispute.

Adam Liptak contributed reporting.