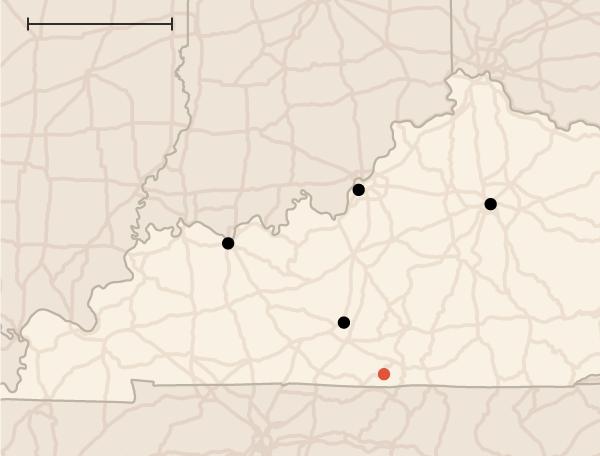

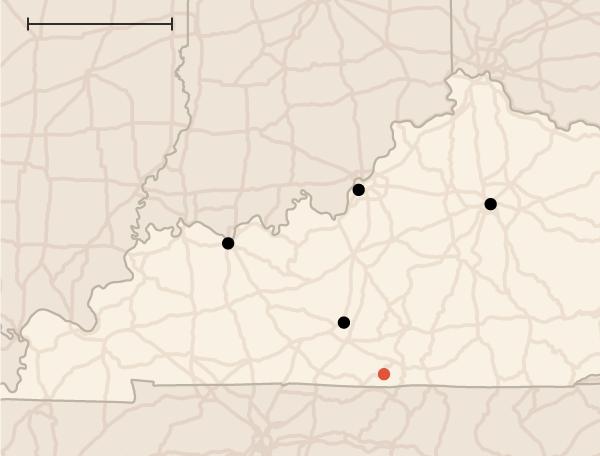

TOMPKINSVILLE, Ky. — This is the Southern barbecue you’ve probably never heard of.

Not baby back ribs thickly crusted with spice rub and served “dry,” as it’s done in Memphis. Not slow-smoked chicken dipped in mayonnaise-based “white” barbecue sauce — a longstanding specialty of Decatur, Ala. Not even mutton, smoked the better part of a day, then sauced with a Worcestershire-and lemon-based “black dip” — the barbecue calling card of Owensboro, Ky.

No, you’ll find this barbecue chiefly here in Monroe County, and a handful of surrounding counties in southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, where it goes by the name shoulder plate, or shoulder sandwich.

In fact, you might question whether to call it barbecue at all.

Just don’t question Anita Hamilton Bartlett, the proprietor of R&S Barbecue in Tompkinsville (population 2,273), just north of the Tennessee state line.

Anita Hamilton Bartlett, the proprietor of R&S Barbecue, serving the pork-shoulder steaks that are both the house specialty and the essence of Monroe County barbecue.CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

Five days a week for the last 27 years, the affable Ms. Bartlett, 60, and her team have followed an immutable ritual. At 5 a.m., they stoke a tall metal firebox behind the restaurant to burn hickory flats (rough-sawed planks) down to embers. At 9:30 a.m., they start the precarious process of transferring the glowing coals on a shovel to a stone hearth built into the back wall of the kitchen. Dips are simmered, slaws (creamy or vinegar) are mixed, and green beans are boiled to within an inch of their lives, in true Southern tradition.

When the one-room restaurant, with its beige metal siding and mismatched tables and chairs, opens at 10:30 a.m., Ms. Bartlett has already started grilling the pork-shoulder steaks that constitute both the house specialty and the essence of Monroe County barbecue.

The window where customers place their orders at R&S Barbecue.CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

Shoulder steaks? Grilled? You won’t find the usual whole pork shoulders here, slow-smoked for half a day. There’s no chopping or shredding the meat to be doused with vinegar sauce, as they do elsewhere in Kentucky and the Carolinas. Monroe County barbecue consists of pork shoulder cut crosswise on a meat saw into pencil-thin steaks, which are grilled, rather than smoked, over hickory embers.

But these pork steaks don’t become barbecue until they are dipped — not once, but twice — in a fiery amalgam of vinegar, melted butter, lard, salt and tongue-torturing doses of black and cayenne peppers.

The first dip is swabbed on the meat as it grills with a miniature cotton mop. Once cooked, the steaks are plunged into a pot of dip, coating the surface with a peppery, buttery veneer. Customers with a masochistic bent order their pork steaks dipped a third time. If you really want to punish yourself, you ask for a separate cup of dip on the side.

The result may make you think of Buffalo wings, with grilled pork steaks standing in for deep-fried chicken. But Buffalo wings don’t taste of wood smoke. You may be reminded of jerky, as the thin slices of pork acquire a firm texture in the 30 minutes or so they spend over the embers.

But ultimately, pork-shoulder steak is like no other barbecue you have eaten. And don’t think of visiting Tompkinsville, the Monroe County seat, without trying it.

Barbecue is a longstanding American tradition, already popular in George Washington’s day, and much of it is rooted in methods cultivated by slaves. The original “barbecue pit” was just that: a hand-dug, ember-filled trench over which young hogs were cooked on sapling crossbars.

But the pork-shoulder steak requires two technologies that followed the Industrial Revolution. The first is the commercial freezer: In order to obtain steaks of the requisite thinness, you need to freeze the pork shoulder solid before slicing. The second is the electric bandsaw, which didn’t come into common use in American butcher shops until the 20th century.

The dipped pork-shoulder steak appears to have originated in Monroe County. But why here, and how?

The pepper dip is the animating spirit of the dish, and according to Ms. Bartlett, that recipe came from an old slave camp in Cave City, an hour’s drive to the northwest. She learned about it from her grandfather, whose ancestors were enslaved there.

Spencer Andrews, of Tompkinsville, with the chicken special at R&S Barbecue. CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

As for pork steaks, Ms. Bartlett learned to cook those from Alex Erwin Tooley, whose father opened the first barbecue restaurant in Tompkinsville, Tooley’s BBQ. Ms. Bartlett went to work there part time in the 1990s, “to help Mr. Tooley out,” she recalled. She found that she preferred cooking and serving to the line work she did at a local textile factory. She ultimately bought the business in 2004.

The pork-shoulder steak is the most perplexing piece of the puzzle. Pork steaks are common in St. Louis, where they’re grilled and served with Maull’s barbecue sauce. But elsewhere in Kentucky (not to mention the rest of the country) people prefer to barbecue whole pork shoulder, a.k.a. Boston butt — named for the barrels, or butts, in which corned pork shoulders were once packed for shipping.

Whole shoulder has obvious advantages — generous marbling, intrinsic tenderness — that make it nearly impossible to overcook and dry out. It takes more time to cook, but the process is considerably less labor intensive than cutting and grilling shoulder steaks.

Wes Berry, an English professor at Western Kentucky University and the author of “The Kentucky Barbecue Book,” believes the pork-shoulder steak’s origins here have to do with Monroe County’s location in the heart of Kentucky farm country, where tobacco was a major crop. Dr. Berry hypothesizes that because the steaks cook quickly and provide a calorie-dense meal in a hurry, they became popular fare to serve to farmhands during harvest season.

Larry Ross owns Ross’s Meat Shop in Tompkinsville; his father founded Ross & Ross Grocery in the 1940s. From his childhood, Mr. Ross, now 71, remembers an African-American bootlegger and jack-of-all-trades named Haskell Evans, who hired himself out to barbecue for farmhands, birthdays and reunions in the 1950s.

“He was the first person to cook pork steaks in Tompkinsville, and he’d buy them from my daddy,” Mr. Ross recalled. He thinks it was Mr. Evans who taught Mr. Tooley how to grill and dip a pork steak.

There’s another connection here: Mr. Evans was Ms. Bartlett’s grandfather — the man who taught her about the incendiary dip.

To produce pork-shoulder steaks, Mr. Ross starts with frozen pork shoulders from Indiana, which he cuts into slices, about 1/4- to 5/8-inch thick, using a meat saw. One 10-pound pork shoulder yields about 20 steaks, enough to feed five or six people.

In a busy week in the summer, when demand peaks, Mr. Ross’s five-person shop ships 20,000 pounds of pork shoulder to more than 50 barbecue joints in 13 counties in southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee.

Randy Walden, the owner of Backyard BBQ, is another Tompkinsville restaurateur with deep roots in pork-shoulder steaks. His grandparents, Paul and Nora Ford, opened the original restaurant, then called Paul and Nora’s, in a one-room shack in 1965. The business subsequently went to Mr. Walden’s uncle, then his brother.

Randy Walden, the owner of Backyard BBQ, makes a dip with ketchup and yellow mustard in addition to the usual vinegar, butter, lard and cayenne.CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

Mr. Walden took over in 2005. He follows the basic Monroe County formula, but with a few subtle twists.

His dip contains ketchup and yellow mustard in addition to the usual vinegar, butter, lard and cayenne; they makes it a whisper sharper and sweeter. (Maybe that’s why he goes through 30 gallons of dip a day.) The grilling time is shorter — 15 minutes — and once cooked, the pork steaks rest in dip on a steam table, which makes them a little moister.

Backyard BBQ also serves an ingenious appetizer: a hard-boiled egg pickled in Monroe County dip for seven days, which gives it a jumpsuit-orange hue and a tart, peppery bite. Desserts run from colorful Funfetti-style frosted cake to deep-fried apple pie — both made by a freelance local baker named Betty Hammer.

At Backyard BBQ, pork-shoulder steak is served with pickled eggs and potato salad. CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

Wherever you go to try pork-shoulder steak, arrive early, suggests Dr. Berry, the English professor. The steaks are at their best between 11 a.m. and noon. By the end of the day, they may taste less like steak and more like jerky.

As for how to eat them like a local, Dr. Berry wiggled his fingers. “You tear the steaks into bite-size pieces, dip them in the extra cup of hot sauce you had the wisdom to order on the side, and pop them into your mouth.”

“Dip the hell out of your pork,” he said. “I love the lingering burn, just enough to keep the endorphins going.”

Preparing Monroe County pork steaks at home is a lot quicker than smoking whole pork shoulder, ribs or barbecued brisket — especially if you’re willing to take some liberties with the recipe.

If you have your butcher on speed dial, procuring pork-shoulder steaks should be easy. Tradition calls for pencil-thin, but the final steaks will be juicier if you order them 1/2- to 3/4-inch thick. Can’t find shoulder steaks? Thin-sliced pork chops work great; buy the fattiest ones you see.

Burning hickory wood to embers at Backyard BBQ.CreditWilliam DeShazer for The New York Times

Tradition calls for grilling the chops over hickory-wood embers, a fuel that is steeped in romance. One easy way to do this in your backyard is to light hickory chunks in a chimney starter and let them burn down to embers. Or grill the pork over a charcoal fire enhanced with a handful of hickory chunks or chips. Gas grillers can place a couple of hickory chunks under the grate over the burners or between the Flavorizer bars of a Weber gas grill.

Monroe County pit masters use a slow-grill process, cooking a quarter-inch-thick shoulder chop for as long as 40 minutes. I prefer a quick grill to darkly sear the outside of the pork, leaving the center juicy and with a blush of pink.

As for the dip, it requires no tinkering, but you will need an ingredient that may not be part of your normal grocery run: lard.

Lard reinforces the porky flavor of the steaks and keeps them rich and moist. If it’s unavailable, use more butter. The preferred souring agent in Monroe County is brown vinegar (a distilled vinegar darkened with caramel coloring), but distilled white vinegar works just fine.