I was descending a Georgian mountain pass in a rented Renault Duster when, rounding a curve with six-foot snow drifts to either side, a dark and narrow tunnel came into view. Looking down the mountain, I could see the other end of it — and an apparently endless convoy of eighteen-wheelers making their way up, entering in the opposite direction. I couldn’t imagine how we’d fit alongside each other, but I pressed on, only to find myself in a black hole. The headlights illuminated nothing. I rolled down the window — one of those useless things you do when beginning to panic — and realized that we were in a cloud of black truck exhaust so thick it was blinding.

I’d come to Georgia to ski — attracted by images of the towering Caucasus Mountains and reports of affordable skiing without the crowds. Those who knew Georgia tended to describe it warmly: exotic and undiscovered, with great food, situated at a crossroads full of history, and changing — its young population striving to show off a post-Soviet identity to the world.

Shacks selling food and drinks on the mountain at the Gudauri Ski Resort.CreditOla Lewitschnik

And that had taken me deep into the Greater Caucasus, a couple of dozen miles from the Russian border, facing down what looked like Central Asia’s entire fleet of big-rig trucks in the smallest tunnel ever built. After a few seconds the smoke dissipated, revealing dozens of headlights in the murk ahead, and just enough space — a matter of inches — to carefully proceed. After what seemed like half an hour (but was really four or five minutes), we emerged on the other side, and eventually made it to Gudauri, Georgia’s largest ski resort, about an hour and a half from the capital city of Tbilisi. With me in the car was my friend Jeff, an American scientist and avid skier, and my Swedish brother-in-law Ola, a snowboarder and hairdresser-turned-photographer by trade

Beginning at around 7,200 feet and rising to 10,000 at its peak, Gudauri’s slopes are above the tree line. When we passed through there was plenty of snow on the ground and sparkling blue skies, which made for strikingly beautiful days on the slopes — nothing but marshmallowy peaks of white in every direction.

Gudauri has around 20 miles of groomed runs with good vertical drops (up to 1,800 feet) and mostly fast, modern lifts. Those open at 10 a.m., and most people seem not to show up until a few hours after that. I was able to ski mostly by myself for the first two hours of the day — the snow well-groomed and just the right amount of soft, the wind light, the weather perfect. I never waited more than 30 seconds for a lift the entire day, even when it began to get crowded after lunch. I ended up spending quite a while at Megobari, the restaurant at the top of the gondola serving snacks like kebab and borscht, and the usual range of drinks but with some surprises too — including a tasty tea with honey, lime, ginger, and a few mystery herbs. There were a few dozen tables and chairs (including some of the beanbag variety) scattered on the snow outside, and an enjoyably obscure musical playlist ranging from klezmer music to “What does the fox say?” It was below freezing, but lovely in the sun.

At the top of the mountain my phone announced calling and messaging rates in Russia, a reminder of how close the border is. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of Russians in Gudauri. But others come here too, and in growing numbers. We ran into an Austrian heli-skiing group and a large group of Chinese visitors. One British-Australian family living in Dubai that I shared a lift with said they’d come a few years in a row, citing the easy three-hour flight as one reason.

For those looking to go off-piste and have a bit of solitude without traveling several hours west to more obscure mountains, Gudauri is the place to be. If one of several heli-ski operators doesn’t appeal, there are other ways to explore the backcountry. At the top of the main gondola a fleet of snowmobiles waits to take skiers up to ungroomed territory — and the gravity-defying ride is arguably even more exciting than getting back down. It’s also possible to ski down the back of the mountain and end up a ways down the road to the north, a short taxi ride back to the lifts. Guides are available to help navigate — recommended considering the avalanche risk.

A few weeks after our trip, a video showing an apparent lift malfunction at Gudauri went viral. In it, we see the lift reversing at high speed down the mountain, the skiers facing the opposite direction having to jump off, and the chairs being swung violently around the lift entrance before ending up in a pile. Luckily no one was killed, and it seems to have been a one-off, freak occurrence. Nevertheless it was, perhaps, a reminder that this isn’t yet quite like skiing in the Alps. That’s also part of Georgia’s draw — only a few hours away, it is a country that manages to feel like an entirely different world.

Georgia has few natural resources, a relatively low profile internationally and powerful neighbors that don’t always play nice. It’s no surprise that it’s eager to attract visitors and show the world what makes it special. And as visitor numbers grow and Georgia emerges as a destination, the country is pinning much hope on its mountains. It struck me that this is a country at an inflection point, with a generation trying to start from scratch in many ways, and make a clean break from the past. That’s part of its appeal. It’s got the basic elements covered: good food, beautiful mountains, dependable snow and welcoming people — the rest they’re figuring out as they go along.

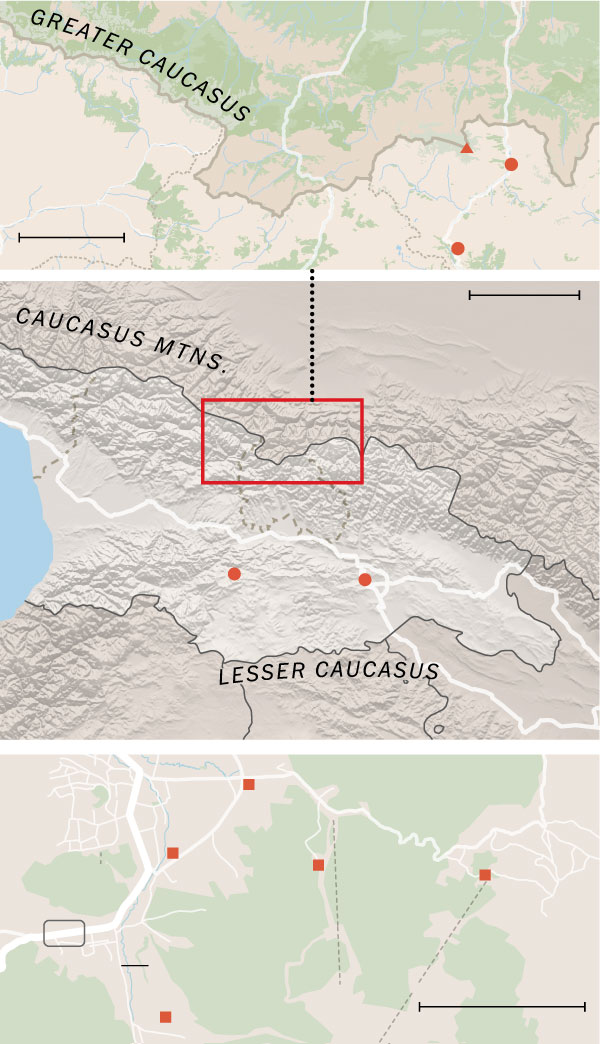

We had begun our Georgia trip in Tbilisi, arriving on an Air Baltic flight from Riga at 4:45 a.m. The immigration officer, a young woman, addressed me in a way I would come to see many more times when making any kind of official or commercial transaction in Georgia: the initial interaction unsmiling, even tense, but giving way quickly to a half-smile and then full-blown friendliness. After locating the Enterprise rental car office, which was just a man in the parking lot who handled our paperwork on the hood of the car under a drizzle, we headed west on a deserted highway in the dark. Before Gudauri, our plan was to visit Bakuriani, a ski and resort town in the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, which run through the southern part of the country into Armenia and Azerbaijan

An hour and a half into the drive, the sun began to rise, revealing the mountain ranges to the north and south, beautiful in the early blue glow. We turned onto a smaller road and began climbing. The towns along the road were gritty — a mixture of old wooden houses and Soviet-style apartment blocks. There were few evergreens on the way up, and no snow, the houses as brown as the mountainside. A lonely brick tower stood in a field, a faint hammer and sickle near the top almost completely faded. Eventually as we gained altitude, the look of things changed — there was more pine, and more snow.

Bakuriani is a ramshackle place, but one with a certain charm — a place of camouflage-jacketed men on horseback; old Russian trucks and buses; elderly ladies selling the traditional cheese-filled bread khachapuri from hole-in-the-wall shops; and families, mostly Georgian and Russian, slipping around on the icy sidewalks. There is one main commercial strip, some very old and beautiful wooden houses on their last legs, and a number of new-build “chalet” style rental houses plus a few larger hotels. There are two main ski areas: Didveli and Kokhta. Didveli has a gondola and a few decent runs plus a couple of spots for some relaxed off-piste exploring. Kokhta has a lift that starts just outside of town, but traffic was gridlocked there when we passed through, and the parking lot full. Much better to continue east down the dirt road to find the newer lift from Mitarbi, which connects to the main Kokhta runs. These latter runs are favored by professional skiers for a bit of practice on the weekends, thanks to fewer crowds and a good vertical drop.

One afternoon I met up with Eka Chagelishvili, vice president of the Georgia Ski Federation, and her two colleagues, Nini Ninua and Anita Gabashvili. They were in town to put on a ski race, one of several they organize around Georgia every year. Nini, 27, had been a professional skier, and Anita was Eka’s daughter, just turned 18. The three regularly travel to mountain villages, hold events and tournaments, and scout for young people to train in everything to do with mountain life — hunting for the next ski champions of Georgia as well as the next generation of managers and business owners in Georgia’s mountain towns. They see their work as a social project as much as a development initiative.

“The children in these villages are really fearless,” Eka told me. “So we want to train them to participate in the Olympics, in world championships, and get medals. We have the resources, we just have to attract people, and that’s an effective way to do it.”

It was snowing outside, and night was starting to fall. Eka made a move toward the bar, suggesting it might be time to have some Jaegermeister.

For those looking for some pleasant runs amid the trees, Bakuriani is not a bad place to do it. It has reliably good snow for around five months of the year, and quite a few good places to eat and drink. It was here that I first encountered chacha, the Georgian spirit made from grapes that’s often referred to as “Georgian vodka.” (Its quality ranges widely, from outright firewater to something pretty refined.) It was often brought to our table, on the house. And Georgian food is perfect post-ski fare: meat stews, cheesy breads, and lots of strong flavors. Some of the highlights: chicken liver chashushli packed with barberry spice and cilantro; khachapuri adjaruli, the classic cheese bread but with a couple of fried eggs and melted butter dropped into the middle; spicy beef ostri slow-cooked in tomato and garlic. Then there’s the semisweet wine, which really grows on you after a bottle or two — at the grocery store a fellow customer recommended I try a bottle of Saperavi said to be a favorite of Joseph Stalin’s. It didn’t disappoint.

Our first night in town we ate at the log cabinlike Mimino, where we ate and drank far too much, then emerged into the cold mountain evening. We asked a group of Georgians where we ought to head next, and someone mentioned the rooftop bar in the new Best Western, just up the road. There we found a group of teenagers bouncing around to hard house music, crowding the D.J. booth. A man who still had his white ski goggles on his head approached us, eager to chat but too drunk to really say much. Russian music videos looking straight out of the 1990s played on a monitor overhead. We stayed 10 minutes and called it a night.

The town around Gudauri, by contrast, is characterless — a collection of mostly bland rental apartments, hotels and a handful of restaurants and bars. During our days skiing in Gudauri, we stayed in the village of Stepantsminda and the Rooms Hotel Kazbegi — a beautifully restored old turbaza, or Soviet-era vacation camp, about a 40-minute drive from the slopes. From my room’s balcony, I sat staring at the looming Mount Kazbegi and the dozens of other snowy peaks rising up on either side of the valley as the fog rolled in.

In Tbilisi on my last night in the country, I sat down with George Gotsiridze, a spatial planner and expert in all things mountains who works closely with the government creating development plans for ski areas. He told me there are many more incredible mountains with perfect snow in the west of the country that don’t have the infrastructure to receive many skiers. And that lack of infrastructure leads to more and more people moving away, leaving the villages depopulated and dying. In a country that’s 60 percent mountainous, skiing and other mountain sports present a huge opportunity to correct that — but it’s a delicate balance.