When their safe houses in Manila were no longer safe, the rebels took shelter at the airy bungalow of Doreen Gamboa Fernandez, a sugar planter’s daughter turned literature professor and food writer.

It was the 1980s, and the Philippines was still in the grip of the strongman Ferdinand Marcos. In a later interview, Ms. Fernandez recalled how her university colleagues had chided her for writing restaurant reviews in such precarious times: “How can you sit there and do the burgis” — Tagalog for bourgeois — “things you do?”

But the leaders of the National Democratic Front knew Ms. Fernandez as an ally. She dressed their bullet wounds and fed them elaborate meals in a dining room hung with art by the Cubist painter Vicente Manansala and the Neorealist Cesar Legaspi.

Then, while her guests recuperated by the pool in the cool shadow of a great acacia, she retreated to her desk and resumed the task of documenting the indigenous cooking traditions — scorned and ignored during centuries of colonialism — of an archipelago spanning more than 7,000 islands and nearly 200 languages.

Hers was a quiet act of subversion. She revolutionized Filipino food simply by treating it as what it is: a cuisine.

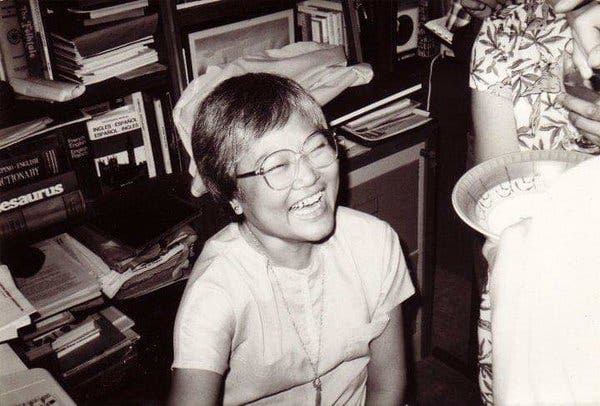

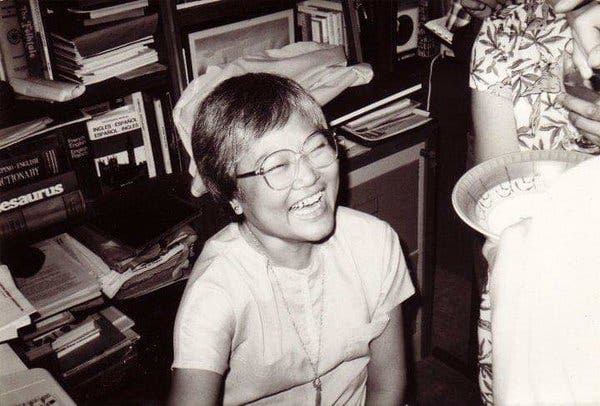

Credit

Ms. Fernandez trained her attention on dishes low and high, from humble carinderias, the roadside stalls where the staff obligingly shooed away flies, and polished “tablecloth” restaurants that had once served almost exclusively American and Spanish food. In the 1950s, she noted, “one did not take bosses, foreigners, dates or V.I.P.s to have Filipino food at a restaurant; it wasn’t considered ‘dignified enough.’”

Her prose was crystalline, at once poetic and direct, whether describing “the distinctive rasp and whisper” of crushed ice in the dessert halo-halo, or freshly cut ubod, the pith of the coconut palm, “that just an hour before had been the heart of a tree.”

In one essay, she outlined the dismantling of a 10-inch-long ulang (freshwater shrimp), opening the head “to catch every bit of orange-creamy delicious fat” and sucking the juices to the tips of the whiskers. In another, she cataloged the textures of the fluted giant clam: “the chewy black mantle, the fat soft center like an oyster supreme, and the muscle which is the best — white and crisp as a pear.”

By 2002, when she suddenly died at age 67 while visiting New York, “she was truly an icon,” said Belinda A. Aquino, the founding director of the Center for Philippine Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Ms. Fernandez’s reputation was international: Raymond Sokolov, a former New York Times food editor, said she was “the most impressive food writer and historian I ever encountered.”

And yet this woman — a literary stylist to rival M.F.K. Fisher and a groundbreaking culinary ethnographer who transformed the way Filipinos saw their food — is barely known in the United States, even among Americans of Filipino descent.

This may be because, until recently, Filipino food itself was an unknown in America. Dishes like kare-kare (oxtail braised with ground peanuts), laing (taro leaves steeped in coconut milk) and dinuguan (pork blood stew) were made almost exclusively by Filipinos for Filipinos, cooked at home or served at the steam-table joints known as turo-turo (point-point, which is how the food is ordered), often half-hidden at the back of a grocery store or next to a carwash.

“When you look for Filipino food, you don’t tell anybody,” said Charles Olalia, the chef of the year-old restaurant Ma’am Sir in Los Angeles. “You go by yourself to the turo-turo.”

But as the population of Filipino-Americans continues to grow — to an estimated four million today from a little over two million in 2000, accounting for nearly 20 percent of all Asian-Americans — a new generation of chefs and restaurateurs is bringing the food to the fore.

In the past few years, ambitious Filipino restaurants and pop-ups have been embraced across the country, including Bad Saint in Washington, D.C., Lasa in Los Angeles, Pinoy Heritage in San Francisco, Musang in Seattle, Karenderya in Nyack, N.Y., and Tanám in Somerville, Mass.

Still, negative stereotypes about Filipino cooking — as “smelly” or “weird” — persist, said Catherine Ceniza Choy, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California at Berkeley. Those born to the cuisine have had to grapple with a sense of shame and uncertainty about its place in America, and their own.

In Ms. Fernandez, these immigrants and children of immigrants are finding a champion of food long maligned and misunderstood.

“She paid respect to it,” said Nicole Ponseca, who runs Maharlika and Jeepney in New York. “She opened the door for me to look at it with dignity.”

Born in 1934, when the Philippines was under American rule, and christened Alicia Dorotea Lucero Gamboa, Ms. Fernandez was always called, personally and professionally, Doreen. (In the Philippines, childhood nicknames tend to last for life.)

Her mother, among the few women of her time to get a medical degree from the University of the Philippines, was assigned to the lone clinic in the genteel town of Silay, in the province of Negros Occidental. Her father was a hacendero, a member of the landed class and the son of a former mayor, who rode out to the cane fields each morning before dawn and courted his future wife by promenading on a horse around the clinic.

Although small, Silay was known as “the Paris of Negros” — a rich cultural capital. (The local sugar planters hosted an annual ball in Manila so sumptuous, the women were said to wear diamonds the size of giants’ teardrops and change gowns 18 times.) But in a reminiscence published in 2002, what Ms. Fernandez remembered most vividly were the church bells that “punctuated the day” until 6 in the evening, when children would stop in their tracks to pray the Angelus, a Roman Catholic devotion.

Unlike the town’s Spanish colonial-era manses, the Gamboa house was built in the 1920s, the family “having ordered practically everything from Sears, Roebuck,” said Maya Besa Roxas, Ms. Fernandez’s niece. During World War II, it was commandeered by the Japanese, then by the Americans. (Gen. Douglas MacArthur paid a visit.)

The family was evacuated to a farm near an air-raid shelter, where, Ms. Fernandez later wrote, “the food was good” — camote (sweet potato) and cassava roots “boiled and dipped in sugar,” and wild berries and weedlike greens that grew among the cane. Her mother improvised a churn to turn carabao’s milk into butter, and when a pig was slaughtered, the children stuffed the meat into intestine casings to make chorizo.

After the war, Ms. Fernandez went to Manila for college and stayed up late at the jazz joint Café Indonesia, eating gado-gado (salad with peanut sauce) while the trumpeter Toots Dila blew his horn. She met the interior designer and architect Wili Fernandez there; they married in 1958. He was the one tapped to write restaurant reviews, in 1968, for The Manila Chronicle.

“He said, like the male chauvinist that he was, ‘Sure I’ll eat, and she’ll write,’” she told an interviewer in 1999. The column, “Pot-au-Feu,” appeared with their joint byline, although the writing was hers alone.

At first she was unsure of the task. “How many words are there for ‘delicious’?” she wrote in the introduction to her 1994 essay collection, “Tikim.” (The title comes from the Tagalog verb tikman: to try a little taste.)

She soon realized that there was more to food writing than merely sensory description. It required “choosing the words that echoed, that reverberated,” she wrote. “And then it was making the readers hear the silence between the echoes, and themselves load them with memory, sensation, and finally meaning.”

In 1972, Marcos imposed martial law and shut down the Chronicle along with most of the country’s newspapers. Shortly after, Ms. Fernandez began teaching at Ateneo de Manila University, where a number of professors had gone underground to fight the regime.

She shared their ideals, but was “not the type you can drag into the streets to carry a placard,” Ms. Aquino said. Instead, Ms. Fernandez contributed in her own way, transcribing revolutionary lectures and acting as a courier for the opposition on her trips abroad. In one possibly apocryphal story, she disguised herself as a nun to visit a friend in prison.

At a 2002 memorial to Ms. Fernandez, Rafael Baylosis, the onetime general secretary of the Communist Party of the Philippines, recounted how she tended his injuries after he was shot by government forces. (Mr. Baylosis is still a rebel leader, protesting the policies of President Rodrigo Duterte.)

After the Chronicle’s demise, Ms. Fernandez wrote about food for Mr. and Ms., a lifestyle magazine whose glossy format camouflaged an anti-Marcos agenda, and, starting in 1986, for The Philippine Daily Inquirer, where her column “In Good Taste” ran for 16 years.

Her work took on a mission: to recover the past. “There was and still is a mountain of knowledge suppressed or glossed over by colonial education,” said Karina Bolasco, the former head of Anvil Publishing, which printed “Tikim.”

On the job, Ms. Fernandez ate everything, but only spoonfuls of sweets, as she had suffered from Type 1 diabetes since she was young. In her 50s, she received a kidney transplant from a nephew. (Her husband, who also had diabetes, died in 1998; they had no children.)

Ms. Bolasco used to accompany Ms. Fernandez on her restaurant forays and witness “the legendary injection” of insulin: “She raised her blouse and matter-of-factly plunged the syringe while describing to me the kind of cuisine the restaurant was famous for.”

If she liked a dish, she might hum a little tune. If she didn’t, “she was never mean,” wrote Chelo Banal-Formoso, her last editor at the Inquirer, in a 2002 notice informing readers of her death.

Her laugh “was discreet but ticklish,” recalled Felice Prudente Sta. Maria, a fellow food writer and friend. “She came from a generation bred to be polite even when criticizing and disagreeing.”

In a tribute after her death, the journalist (and future legislator) Teddy Casiño described Ms. Fernandez as “a transformed burgis.” Approached with a tale of distress, she immediately pulled out her checkbook.

Still, she never quite shed the assured aura of the aristocrat, even in her preferred uniform of denim and comfortable flats — “no jewelry, no expensive watches, no heels even at formals,” Ms. Bolasco said.

Ms. Fernandez wore her hair in a bob that turned silver in her 60s. For Jonathan Chua, the dean of the School of Humanities at the Ateneo de Manila, the curves of her face called to mind Mrs. Potts, the teapot voiced by Angela Lansbury in the animated film “Beauty and the Beast.”

Some of her readers today might be surprised to learn that she didn’t cook. This wasn’t unusual for an educated Filipino woman of her time. A housekeeper made the memorable meals served to guests.

But Ms. Fernandez never took this labor for granted, and in her work she honored it, focusing on home cooks, sidewalk vendors and those who rely on the earth’s bounty — farmers, fishermen and foragers, who know “when the maliputo (yellowfin jack) enter the Pansipit river to spawn; when and where the wild edible fern is to be found; which bananas have which sweetness or flavor; which mushrooms are safe and what rains bring them.”

On a trip to New York in June 2002, Ms. Fernandez fell ill and died of complications from pneumonia. She was so prolific that she had left behind weeks of columns, along with two unfinished book manuscripts.

For the Filipino-American chefs and restaurateurs now seeking out Ms. Fernandez’s works, it isn’t easy: They were published only in the Philippines and are almost entirely out of print.

After opening Bad Saint in the fall of 2015, Genevieve Villamora bought everything from Ms. Fernandez’s oeuvre that she could find, scouring used-books websites. Today, copies can command more than $700, if they are available at all.

Mr. Olalia, the chef at Ma’am Sir, raided his mother’s bookshelves, and hunted for rare imported compilations at Now Serving, a Los Angeles cookbook shop opened in 2017 by the chef Ken Concepcion and his wife, Michelle Mungcal. Ms. Ponseca was lucky enough to receive “Tikim” in the mail, sent out of the blue by an Instagram follower.

All of them found revelation in these battered pages.

“The victors always tell the story,” Mr. Olalia said. But Ms. Fernandez’s research showed that Filipino food was more than a motley of imposed external influences. Ingredients and techniques from other cultures weren’t simply borrowed, but adapted and “indigenized,” as she put it, to please the local palate.

Last year, Ms. Choy lobbied the Dutch publisher Brill to reprint “Tikim.” In a foreword to the new edition coming out in December, the San Francisco chef and activist Aileen Suzara praises Ms. Fernandez for upending the colonial narrative and evoking “the luminous possibilities of a living culture.”

In the Philippines, Anvil is readying a reissue of “Tikim,” at a time when the country is once more beset by extrajudicial violence and government crackdowns on the press.

With Ms. Fernandez’s intellectual rigor and commitment to clarity, “she wouldn’t have survived this era of deep fakes and truth decay,” Ms. Bolasco said.

Or maybe, she added, “she would have been the fiercest warrior to fight them.”