“Stay here and guard the castle,” I would say to my dog, Dusty, every time I left our condo. Over the years, his eyes — one blue, one brown — had become washed with gray, his sight was failing, and his hips were becoming tight. He was hardly a guard dog.

When I came home, he no longer greeted me at the door but would raise his nose in welcome. I gave him peanut butter for his bravery, sometimes with painkillers to help with his hips.

Eleven years earlier, I adopted Dusty-Danger Dog (his full name) from the Town Lake Animal Shelter in Austin. I stopped by the shelter one day, came back the next, and Dusty was the only dog who remembered me. He had pointy ears like a giant fox and was at risk of being euthanized.

Since then, he and I traveled the country in my bumper-stickered Toyota pickup, visiting 28 states while putting 290,000 miles on that truck. During our years in Austin, Dusty became a local legend, helping to raise thousands of dollars for nonprofit organizations such as Austin Bat Cave and the Fusebox Festival. For a monetary donation to the nonprofit, Dusty and I would take someone’s dog on a special date, and I would write an essay about it for the donor. This raised a surprisingly large amount of money.

For this, Austin’s mayor proclaimed August 17 (this very weekend!) “Dusty-Danger Dog Day,” citing Dusty’s “meaningful contributions to the city and people of Austin with volunteerism, fund-raising and four-legged ambassadorship for the arts, environment, education and health.”

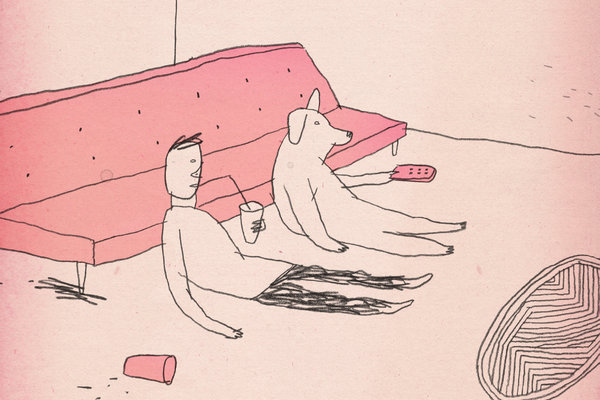

On a personal level, Dusty became the manager of my life. He got me up in the morning with a lick to my face. When he ate, I ate. In the middle of the day, he forced me to turn off my computer and go for a walk.

I enjoyed the sun on my face and the smell of wildflowers. We shared sandwiches and pizza and watched comic-book movies together. Dusty never cared if I changed my clothes. I would read to him from my favorite book, “The Little Prince,” lines like: “You are responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.”

I had those words tattooed to my arm.

Dusty taught me everything I needed to know about life, but over the years there had been something missing. My friends Ben and Rachel insisted I join a dating app to expand my horizons. That’s how they met, but I loathed the idea.

Why would I want to expand my life? I had a dog, a place to live, a pickup truck smothered in bumper stickers. But out of curiosity (or God knows what), I humored them. I created a Tinder account with a picture of Dusty as my profile picture. No one matched with me until Rachel explained that I was swiping in the wrong direction. The first time I swiped right, I matched.

On my date with Ilse, we had salad and calamari. She was shy, lovely and, as a person with diabetes, checked her blood sugar when food came. On our second date, we drank wine, bowled at a speakeasy, and talked about Dusty and her cats, Dori Ann Gray and Oscar Wilde. On our third date, Ilse held my hand and shared that she had been assaulted in New Orleans in June, years ago.

As a result, June makes her sad, and so does New Orleans, a town she loved and lost, and Dusty and I had come to love in our travels. As a landscape architect, she works with plants and water. She doesn’t like comic-book movies and watches the Hallmark Channel. She makes me eat brussels sprouts, which are surprisingly tolerable on pizza.

With Dusty everything was safe and there was never a compromise, but with Ilse I had to listen and negotiate. Ilse knew how to manage her life, and she made me change. Sometimes she made me change my clothes.

After a year of dating, Ilse began pushing for marriage, an idea that terrified me. I’m not afraid of commitment; I’m afraid of divorce, of failure. But I was also afraid of losing Ilse. She said it’s difficult for an entrepreneurial woman in her 30s to find love with someone who has a good job and is nice to animals.

We had a back and forth, like playing chess. For every argument I made for not getting married and giving up my perfect life, she had a better counter argument. She used words like “us” and “ours,” words I had previously reserved for my relationship with Dusty.

One evening, Ilse said if I wasn’t going to be with her, I had to let her go so she could find someone else. As much as I loved my dog and my perfect life, I didn’t want to lose Ilse, especially knowing I was about to lose Dusty, whose health had deteriorated to the point where he could barely walk.

The next morning, I told Dusty, as usual, to stay home and guard the castle. I was driving to the University of Texas at San Antonio at 5:30 a.m. to lecture about subjectivity and causality when I was hit from behind by what I think was a drunken driver. The collision launched my truck, at 70 miles per hour, into a cement barrier, where it was ripped to pieces. The force of the impact peeled two of my bumper stickers from the tailgate.

If it weren’t for the airbag, I would be dead. As the paramedics cut me from the truck, all I said was: “Take care of my dog, take care of my dog, take care of my dog.” In that moment, coughing from airbag dust, I thought none of this was worth anything unless I had something more to live for.

So I designed an elaborate, weeklong wedding proposal that included a writing class, rock climbing and a party at an urban winery. After Ilse said yes, she moved into what is now our condo, bringing her cat, Dori, who became fast friends with Dusty, napping together and sharing food.

My goal was to marry in June so Ilse could reclaim that month with a fond memory. I asked Dusty to be in my wedding party. “Maybe he can tie my tie,” I thought. Ilse and I registered for small appliances and dishes. Everything changed.

Two weeks before our wedding, Dusty caught his paw on the rug as he tried to get up from his nap with Dori. He hit the floor hard and whimpered. I held him and gave him peanut butter with painkillers. He looked at Ilse as she stacked wedding gifts in our office, and then he looked at me.

His eyes said, “It’s time.”

I took Dusty for one last walk so he could feel the sun on his nose. We had treats and watched a comic-book movie together. The vet gave him drugs. Dusty died at home, in my arms, his nose on my knee, only days before Ilse and I got married. As he closed his eyes, I whispered, “I’ll guard the castle.” We wrapped him in blankets, placed him in a basket and a white van took him away.

Within minutes I was lost, pacing the living room, looking out the window for the white van to come back, hoping the vet had made a mistake, wishing everything could return to the way it had been. Ilse asked if I wanted to hike or swim to take my mind off Dusty, but I couldn’t.

“All I ask is you smile for pictures,” Ilse said as our wedding approached. We had been taking classes for our first dance to Wilco’s “California Stars,” the song we first danced to in my kitchen, and I could hardly shuffle my feet.

When I went to pick up Dusty’s ashes at the funeral home, they also gave me wildflower seeds to plant in his name. I placed his urn in the back seat of my new car and belted it in. We drove by our favorite pizzeria, our favorite parks, our favorite everythings in Austin, and as we drove, I thought I saw Dusty’s shape in a cloud. I knew he would always be with me.

On the day of the wedding, I led a team of true believers to Town Lake, not far from where I adopted Dusty, to plant those wildflowers. I bought kazoos and we gave him a 21-kazoo salute.

Five hours later, after my groomsmen had tied my tie, Ilse and I stood before friends and family as my best man read from “The Little Prince,” ending with: “You are responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.”

I thought I had been responsible for Dusty, but really he had been responsible for me, and now he was passing the torch to Ilse, my new partner for smelling the wildflowers.

With the sun on my face, I said, “I do.”