Scabies can be controlled with a pill or two, and the protective effect lasts for years, scientists reported on Wednesday.

At present, the standard remedy is a skin cream with an insecticide that does not provide long-term protection. In poor countries, pills can be distributed throughout a village, ridding whole communities of the parasite.

While not fatal, scabies causes profound misery; many people find even the thought of it repulsive. Two years ago, it was added to the World Health Organization’s list of neglected tropical diseases.

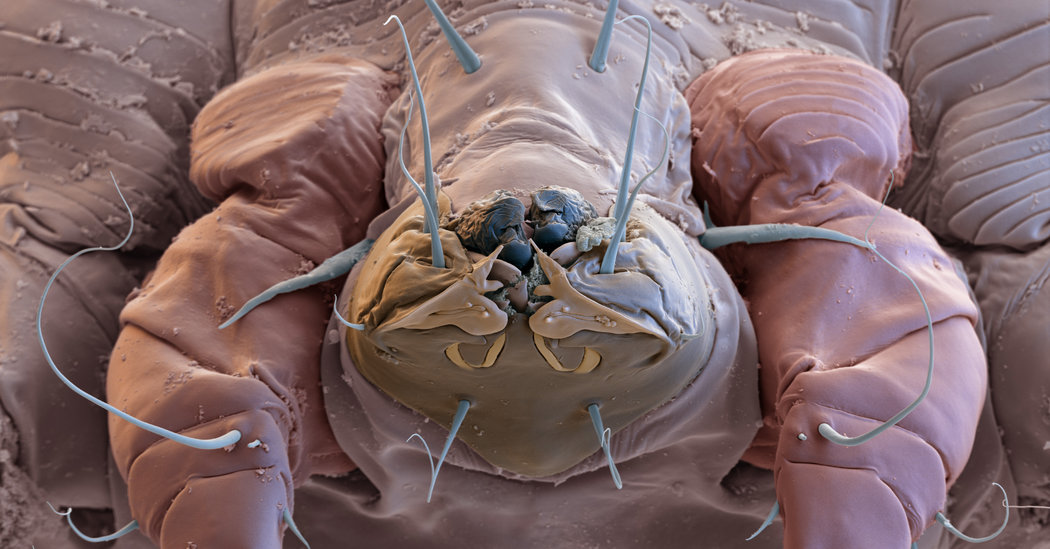

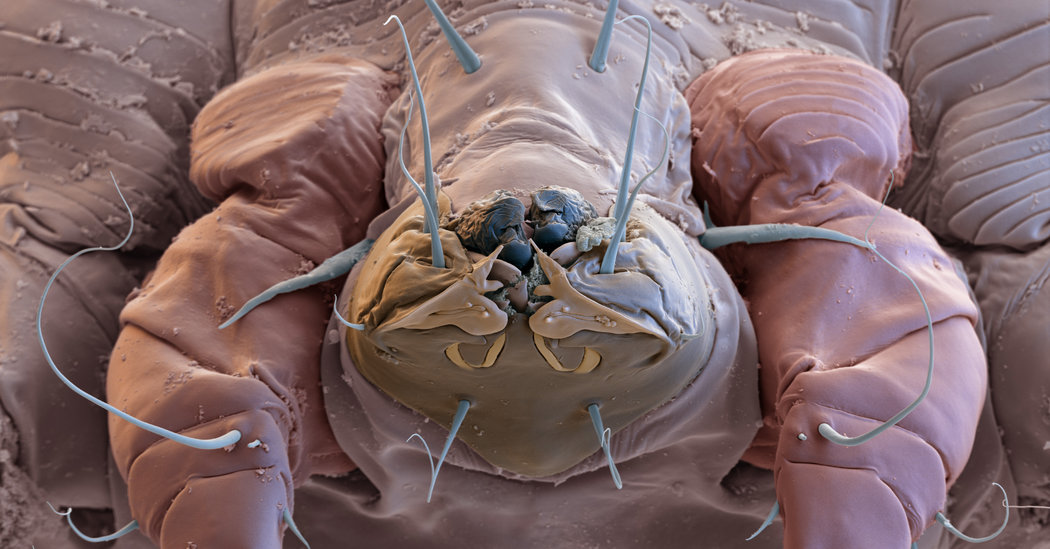

Scabies is an infestation of tiny mites that burrow under the skin. Victims suffer from relentless itching and develop an angry rash, which is an allergic reaction to the eggs and feces the females deposit as they tunnel.

Scratching the rash may lead to impetigo, a bacterial skin infection with oozing sores.

Scabies is most common in poor countries but can be found anywhere. It has been diagnosed in American high-school wrestling teams. In January, infestations were detected in firefighters at two New York City firehouses, one of which had to be closed for decontamination.

In the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Australian and Fijian researchers tested three treatment regimens in three groups of isolated island villages in Fiji.

A third got the standard treatment prescribed in Fiji: skin lotion containing permethrin was given to people with scabies and their family members. (Permethrin is an insecticide used in insect-repellent clothing and in some mosquito nets.)

In the second group, everyone in the village got the lotion.

In the third group, everyone in the village who agreed to participate got one ivermectin pill; those with confirmed scabies got a second pill a week later.

Ivermectin, which was discovered in Streptomyces avermitilis bacteria in 1975, is a powerful drug that kills many types of parasitic worms. Because ivermectin lingers in the blood, it also kills insects that bite humans, including mosquitoes, lice and mites.

Nonetheless, the drug is considered safe enough to give to almost everyone except the youngest infants and pregnant women. It is also used in pets to kill heartworms, for example. Its inventors shared the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

After two years of follow-up in Fiji, less than 4 percent of the inhabitants of the villages that got ivermectin still had scabies. By contrast, the prevalence rate in the villages that got standard care was 15 percent. In the villages where inhabitants got topical permethrin, the figure was 13.5 percent.

In the ivermectin group, secondary infections like impetigo were 90 percent less common after two years than they had been when the trial began — far lower than in the other two villages.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]

Effective as mass distribution of ivermectin was, the authors wrote, it still needs to be tested in larger, less-isolated populations to see if the overall protective effect persists.

In 1971, a global survey of dermatologists for the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested that scabies was on the increase all around the world, for unknown reasons.

In the years following World War II, it was not uncommon to treat scabies with a lotion containing DDT, especially in military hospitals. Use of topical DDT was later linked to some cancers by the World Health Organization.