“Coffee,” said Buzzy O’Keeffe, the owner of the renowned River Café, in Brooklyn, “is the last thing a restaurant diner tastes — so it better be good.”

For Mr. O’Keeffe, it seems, it’s never good enough. Every couple of weeks he assembles his chef and several staff members for a blind tasting of brews from around the world. Those that pass muster — typically under 20 percent — might find their way into the restaurant’s ever changing house blend, which typically contains beans from Colombia, Brazil, Sumatra and Costa Rica.

“I have been searching for the perfect coffee since my thirties,” said Mr. O’Keeffe, now in his discriminating seventies. “I have found that even the perfect blend will vary from time to time, depending on the year’s crop — something like wine but not quite as fickle.”

Last year, when I learned that he was planning a trip to coffee plantations in Costa Rica, I asked if I could tag along, a caffeinated cohort one might say.

On a balmy Sunday evening we arrived in San José, the country’s sprawling capital. We drove 20 minutes to the town of Belen and the Costa Rica Marriott Hotel Hacienda Belen, a delightful Spanish colonial hotel with 299 rooms.

On our first morning we enjoyed a typical Costa Rican breakfast. It commenced with spectacular fruits and the country’s omnipresent national dish, called “gallo pinto” (spotted rooster). It’s a simple but tasty combination of black beans, rice, onions and cilantro. Our gallo pinto was served with the customary scrambled eggs, tortillas and natilla, which is like sour cream but not as thick. And on the table was a small bottle of the popular condiment called Lizano, which is like a sweet-savory steak sauce.

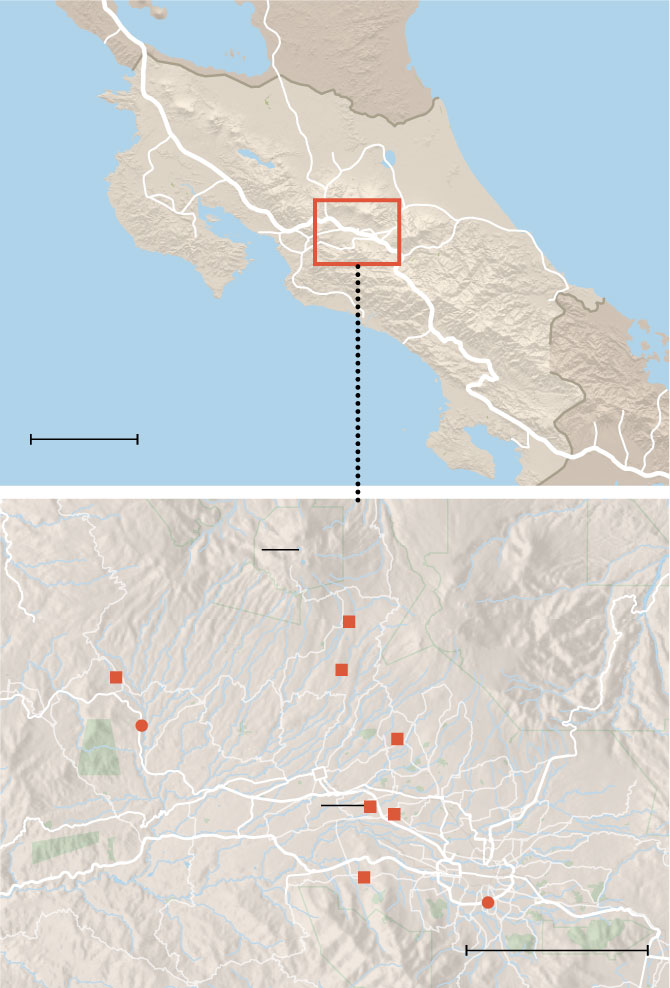

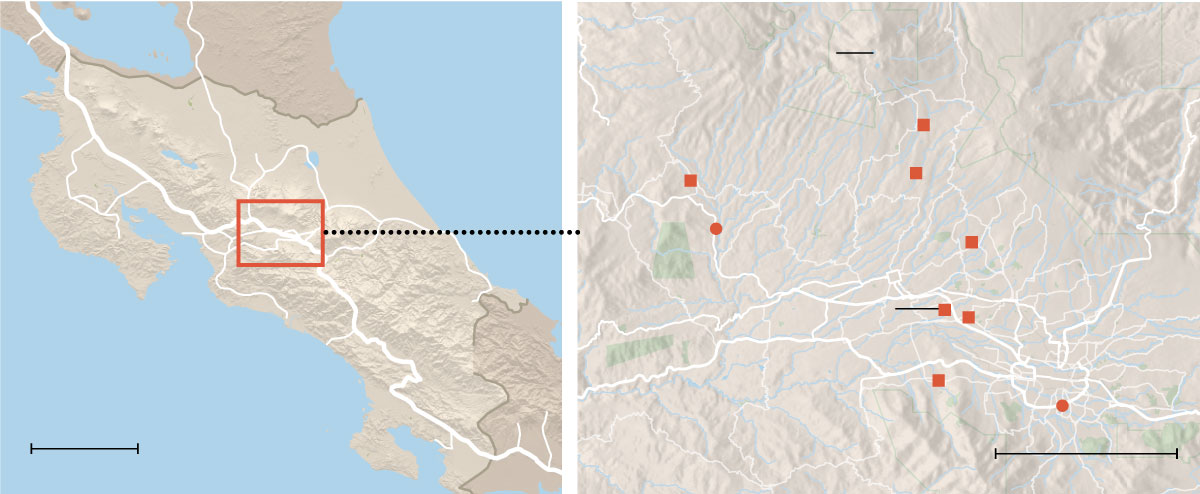

Caribbean

Sea

Costa Rica

Pacific Ocean

Poás Volcano

La Casona de

Doña Julia

Espíritu Santo

Coffee Tour

Hacienda

Alsacia

central

valley

Finca Rosa

Blanca

Costa Rica Marriott

Hotel Hacienda Belen

Café Britt

Street data from OpenStreetMap

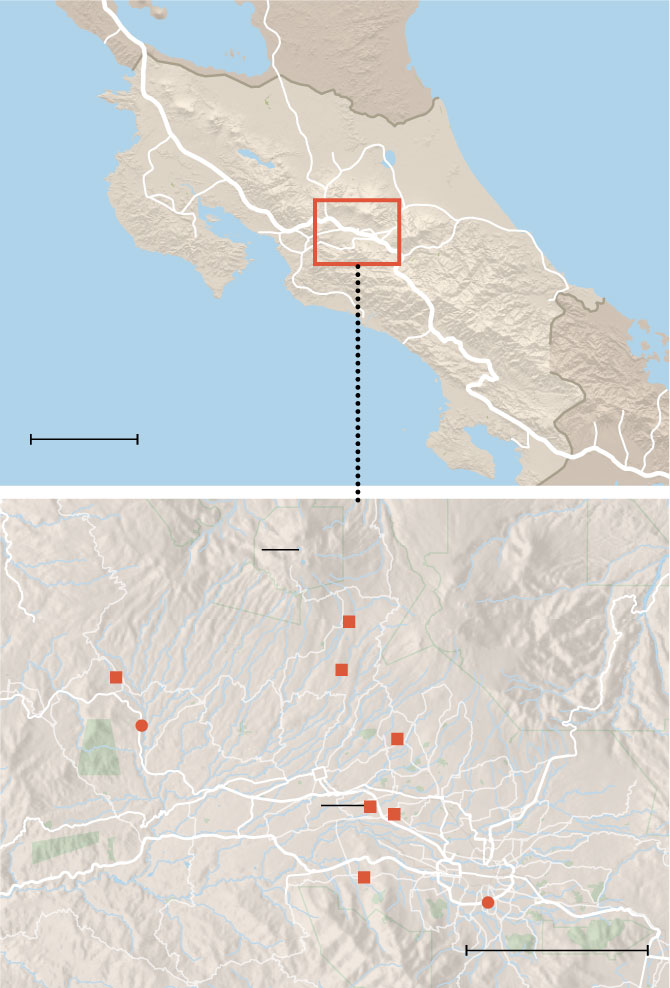

Poás Volcano

Caribbean

Sea

La Casona de

Doña Julia

Espíritu Santo

Coffee Tour

Costa Rica

Hacienda

Alsacia

central

valley

Finca Rosa

Blanca

Costa Rica Marriott

Hotel Hacienda Belen

Café Britt

Pacific Ocean

Street data from OpenStreetMap

San José is in the country’s mountainous Central Valley. Often overlooked by beachgoers, it is the heart of the country’s coffee industry, with the ideal volcanic soil and optimal climate conditions for its cultivation. Coffee originally drifted westward from Ethiopia, and in the 19th century the colonial government strongly promoted its production. In the ensuing decades it improved the lives of poor farmers — and fattened the coffers of colonial oligarchs, and is one of the country’s most important exports.

The Central Valley affords visitors much more than coffee. Within a two-to-three-hour drive you’ll find river rafting, hiking, waterfalls, rainforest expeditions, thermal springs and bird watching. For the intrepid sightseer, a two-and-a-half-hour drive takes you to the popular Poás volcano (still active), where you can ascend nearly 9,000 feet by car and gaze down into a gurgling, steaming, sulfurous, molten crater.

Mr. O’Keeffe, tall, dapper, and scholarly looking, was interested in comparing freshly roasted Arabica coffee (Arabica beans are the highest quality; robusta beans are generally for the mass market) with what he purchases once the beans are exported to New York. (They should be very similar if delivered promptly and shielded from air and sunlight.) Our first destination was a coffee company outside of San José called Café Britt. It was founded in 1985 by Steve Aronson, an American now living in Costa Rica and a world authority on coffee whose career dates to the early 1970s as an apprentice taster in Manhattan’s former coffee district, near the South Street Seaport.

“At that time all of the good Costa Rican coffee was exported, and the inferior stuff stayed here,” Mr. Aronson explained. He wanted to change that. He launched the first gourmet coffee growing and roasting company in the country and began domestic distribution while at the same time building his export trade. Today Britt coffee is sold throughout much of Central and South America.

The company conducts hourlong tours of its half-acre educational plantation, followed by a discussion and a short film. Guests are taken through the steps of coffee bean processing from planting seedlings to harvesting what are called “coffee cherries,” large red pods that hold two coffee beans each. Newly planted coffee bushes require three to four years to produce cherries. Once removed the beans are dried, husked in a special machine, graded and packed for transport. Some operations, like Britt, roast their beans in house before shipping. At the end of our tour came a “cupping,” the professional term for coffee assessments. (The cupping is not part of the basic tour; there is a $20 supplement per person.)

“O.K., when we begin will the coffee still be hot?” Mr. O’Keeffe inquired, sitting at a big round table holding about 20 half-filled ceramic cups. (He is a stickler for the proper coffee temperature at his restaurant.) As with wine, the temperature at which coffee is served at professional tastings alters its characteristics — hot coffee releases more aromatics.

The coffee cups on the table contained brews from Arabica beans cultivated at different altitudes. Among them: Tarrazu, which thrives in the high mountains southwest of San José (typically characterized as medium-bodied and high in acid, with hints of chocolate); Tres Rios, east of the capital (also with ample acid and a full, smooth body); Central Valley (the high altitude region west of the capital and known for smooth and full bodied brews); and Orosí, to the southeast, said to be almost floral, although that eluded us amateurs.

Mr. Aronson called out instructions.

“Stir the coffee, then place your nose so it’s almost touching it. Sniff. Then lift the cup over your lip and slurp.” Expectoration optional.

Mr. O’Keeffe tasted each brew methodically, returning to several for another slurp. He said that, for the most part, the differences were more subtle than he had expected.

“Being down here, I thought I’d be tasting peaches or something,” he laughed.

The Britt tour, about an hour, concludes with a Costa Rican buffet lunch.

Heading to Starbucks Central

The following morning we drove 5,000 feet above the lushly carpeted valley on the slopes of the irascible Poás Volcano, to the two-year-old Starbucks global agronomy complex and visitors’ center called Hacienda Alsacia. I would go for the view alone. Situated on a 600-acre working plantation, it is where the company conducts farming research and development, creates programs to help small-scale coffee farmers around the world boost their income and educates the public about what Starbucks calls sustainable coffee.

The hour-and-a-half tour is similar to that at Britt but a little longer and more hands on. It starts with demonstrations on how seedlings are planted and allowed to mature, and on how to dry beans by raking them over hot cement. At one point the tour guide asked for a volunteer to help dry the beans under a wilting sun. There were no takers. He drafted Mr. O’Keefe, who stepped forward wearing the bemused expression of someone called onto the stage by a magician. Four round trips with the rake was enough. A cupping followed, and Mr. O’Keeffe noted that, not surprisingly, the darker the roast the more intensely acidic and flavorful the coffee. Think of Starbucks’ sharp and heavily roasted — some say over-roasted — product.

Winding down the mountain we happened upon La Casona de Doña Julia, two large barnlike structures with a sign reading “Comida Auténticamente Costarricense” (Authentic Costa Rican Cuisine). We sat at a long picnic table and sipped chilled Imperial, a Costa Rican beer. Actually, by the time it arrived it was only half chilled. A word about dining in Costa Rica restaurants: Service is slow, really slow, take-a-walk-between-courses slow.

The menu carried all of the country’s greatest hits, starting with a platter with gallo pinto along with fried chorizo, chicharrón (a dense pleasantly salty sausage), tortillas, salchichon (a smoked sausage) refried beans, fried yuca, fried bananas, salad, and delicious chicken with a sprinkling of Lizano sauce. Another Costa Rican staple is called torta de queso, which is kind of a thick, round torte made of melted fresh cheese and ground corn. Every day, at 4 p.m., most Costa Ricans downshift the wheels of commerce to relax with a wedge of torta de queso and coffee.

I was eager to sample the national dessert, tres leches, which is a sponge cake drizzled with three sweetened milks: evaporated, condensed and fresh. You find it everywhere. Except Doña Julia.

A luxurious brew

If you are looking for a little opulence with your Arabica, it can be found half an hour from the airport at Finca Rosa Blanca Coffee Plantation Resort. It is snuggled amid 30 undulating acres of coffee — everything is assiduously eco-friendly and sustainable — with 13 tropically themed rooms and two suites (doubles around $350 with tax).

The daily two-and-a-half-hour coffee program, which is open to non-guests with reservations ($40 per person), is as much about rainforest ecology and preservation as what you sip at breakfast. Those of an avian bent can roam the heavily shaded 30-acre property to seek out some of the nearly 250 species of tropical birds.

“We’re all about being green and sustainable,” said the farm supervisor and head roaster, Carlos Sanchéz. “Even the hotel — we built it with recyclable materials.”

Our final stop was in the town of Naranjo, another short hop from the city, at the Espíritu Santo Coffee Tour. The coffee itinerary — by now I could moonlight as a tour guide — in a 600-acre plantation is unveiled in seven stages, from planting to merchandising. It can be a long lesson, but the engaging guides sense when to pickup the pace. And not least, they are great with children.

That night, over dinner at Bacchus Ristorante in San José, Mr. O’Keeffe reflected upon our four-day coffee trek.

“It was interesting to see firsthand how sensitive coffee is to the elements, and to the politics of where it is grown,” he observed. “Costa Rica has such an advantage being located here in this pretty much protected valley and in a peaceful, safe country.”

Hurtling through so many cups of coffee in four days was educational, he noted, as coffee, like wine, is a moving target — and the tasting never stops.

This reminded Mr. O’Keeffe of a little story he sometimes pulls out of his wallet when in the presence of wine connoisseurs, about a television skit about wine tasting. “One actor said ‘I taste raspberries!’ and another said ‘I taste pears, peaches, cherries!’ and so forth,” he said. When it came to the final actor, “He said, ‘I taste crushed grapes.’ It’s like that with coffee tours.”

If you go

Addresses in San José lack street numbers. It’s all descriptive. The directions for one house included locating two barking dogs. The business address of our hotel, Costa Rica Marriott Hotel Hacienda Belen: “700 meters from west of Firestone/Bridgestone (tire stores/auto repair shops).” Rooms start at $180 a night.

From a distance, Soda Tapia across from the popular La Sabana Park and the Museo de Arte Costarricense in San José looks like a place someplace you would approach on roller skates, sort of a 1950s burger and fries drive-in with wraparound red-and-white awnings. “Soda” is the local term for a casual eatery and sandwich shop. Open late, Soda Tapia attracts a steady stream of well-nourished patrons and families, with a giant menu that includes delicious tropical fruit shakes. Sandwiches cost 2,500 to 3,800 colones, about $6; fruit shakes, 1,400 to 1,800 colones, about $3.

Bacchus Ristorante, in San José’s Santa Ana neighborhood, is a colorful and comfortable Mediterranean style spot that attracts a youngish crowd. Among dishes to look for are the wild mushroom ravioli, lamb medallion with pesto risotto, steak with a chimichurri-style sauce, and panna cotta with a fruit sauce spiked with Amaretto. Dinner about $60 for two.

Bryan Miller is a former reporter for The New York Times.