Want climate news in your inbox? Sign up here for Climate Fwd:, our email newsletter.

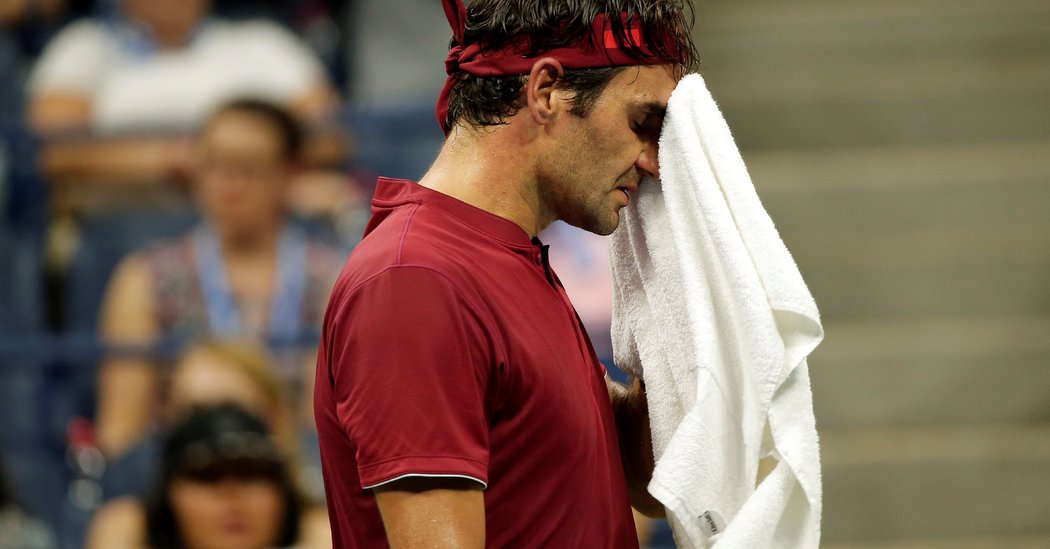

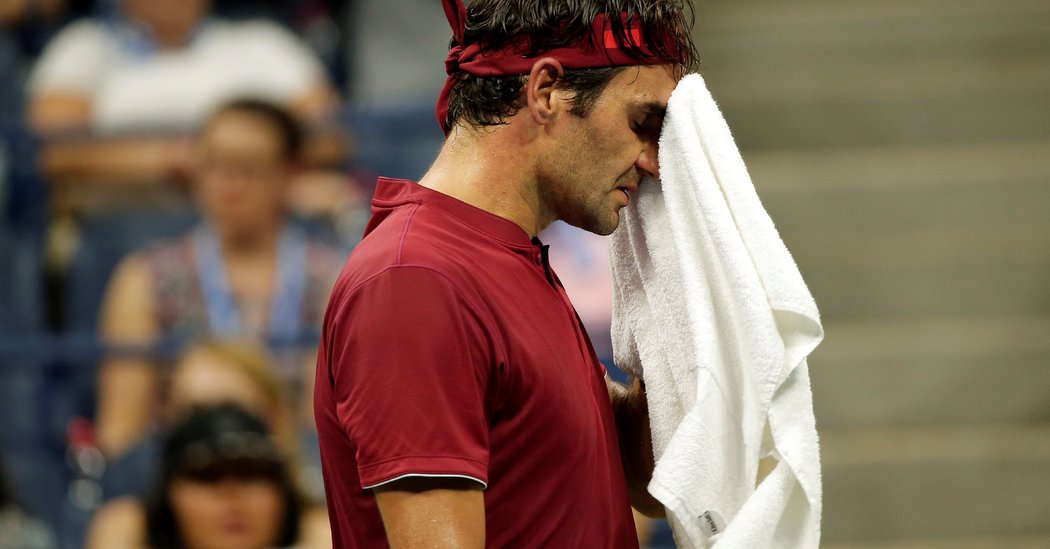

Roger Federer, one of the world’s greatest tennis players, may have become an unwitting spokesman for the effects of climate change on Monday at the U.S. Open.

Federer, who is ranked No. 2, seemed to struggle all night in the heat and humidity at Arthur Ashe Stadium, losing in a fourth-round upset to John Millman, an Australian ranked 55th.

“It was hot,” Federer said. It “was just one of those nights where I guess I felt I couldn’t get air; there was no circulation at all.”

This was the first time Federer, who won the U.S. Open five consecutive times from 2004 to 2008, lost to a player outside the top 50 at the tournament.

To some, the comments by Federer, 37, may sound like sour grapes. But they also underscore a growing problem: increasing nighttime temperatures.

Under climate change, overall temperatures are rising — 2018 is on track to be the fourth-warmest year on record — but the warming is not happening evenly. Summer nights have warmed at nearly twice the rate of summer days. Average overnight low temperatures in the United States have increased 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit per century since 1895, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

While daytime temperatures above 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) have been a persistent problem at this U.S. Open, forcing officials to offer players heat breaks and suspend junior matches, conditions Monday night were not much cooler. Temperatures hovered in the mid-80s, with the humidity for much of the match above 70 percent.

The preliminary overnight low at nearby La Guardia Airport was 80 degrees. If it is made official, it will set a daily record, said Jake Crouch, a physical scientist at NOAA.

The heat index, which combines heat and humidity to indicate a “feels like” temperature, was in the 90s.

“At 10:51 p.m. the heat index was 95 — that’s pretty incredible,” Mr. Crouch said. “That’s a hot heat index in the middle of the summer, in the middle of the day, for New York.”

Short-term weather conditions are not the same as long-term changes to the climate, and a few hot days do not prove a trend. But the unusual heat and humidity that appeared to strain Federer are in keeping with the changes that atmospheric scientists are seeing under human-caused global warming.

Normally this time of year, the daytime high temperature tops out at 80 degrees, with overnight temperatures in the 60s.

Humidity at high temperatures stymies a key cooling mechanism for the body, sweating.

“When we exercise, our primary means of cooling ourselves off is to sweat,” said Lacy Alexander, an associate professor of kinesiology at Pennsylvania State University. “For every gram of sweat we evaporate, we liberate heat.”

But when the air is too humid, the sweat doesn’t evaporate; it drips. “It provides no cooling capacity for the body,” Dr. Alexander said.

“You have soaking wet pants, soaking wet everything,” Federer said after the match.

He also said Millman might have had an advantage because “he maybe comes from one of the most humid places on earth.” Millman is from Brisbane, Australia, which is cooler but steamier than Federer’s off-season training base in Dubai.

The body has some capacity to adapt to warmer temperatures through exposure. But being maladapted to heat is mostly a problem for non-athletes, Dr. Alexander said.

For an athlete like Federer, “that high level of training on a day-to-day basis imparts a degree of heat acclimation just because of high fitness,” she said.

For more news on climate and the environment, follow @NYTClimate on Twitter.

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a reporter on the climate team. Before joining The Times in 2017, she covered science and the environment for Popular Science. @kendrawrites