Robert Pear, a reporter whose understated demeanor belied a tenacious pursuit of sources and scoops during his 40 years at The New York Times covering health care and other critical national issues, died on Tuesday in Rockville, Md. He was 69.

His death, from complications of a stroke, was confirmed by his brother, Douglas, his only immediate survivor.

Mr. Pear went about his reporting meticulously and, to the wider public, inconspicuously. Appearances as a talking head reporter on cable news were not for him. Colleagues described him as an almost sphinxlike good listener, working in the Washington bureau newsroom standing up at a specially built desk that he had gotten used to after undergoing back surgery.

Yet his reporting — exacting, authoritative and closely read, particularly in Washington — spoke volumes. Allan Dodds Frank, an Emmy Award-winning business journalist, described him in an email as “the most important reporter in Washington you have never heard of.”

He and Mr. Pear worked together at the old Washington Star, where Mr. Pear was assigned to general news and later to Capitol Hill before The Times hired him in 1979. Working out of the Washington bureau, he focused on civil rights, immigration, foreign policy and social policy.

“Everyone in Washington knows that the federal budget cannot be released until Robert has published it in advance in The Times,” two of his editors, Jonathan Landman and Andrew Rosenthal, wrote in a Times in-house newsletter in 2000.

Mr. Pear influenced the public discourse most by mastering the details of health care delivery. He would then explain those complexities to readers with unusual clarity, as well as the impact of proposed legislation to revamp the system.

He once even visited a factory not far from the Capitol to disprove Otto von Bismarck’s aphorism that “if you like laws and sausages, you should never watch either being made.” In many ways, he wrote, “that quotation is offensive to sausage makers.”

Recently, he was reporting on Republican efforts to dismantle the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act.

In the last article to carry his byline, in The Times on April 20, he wrote that while President Trump and Republicans in Congress say they are committed to protecting people with pre-existing medical conditions, many would have significantly less protection under their health care revisions.

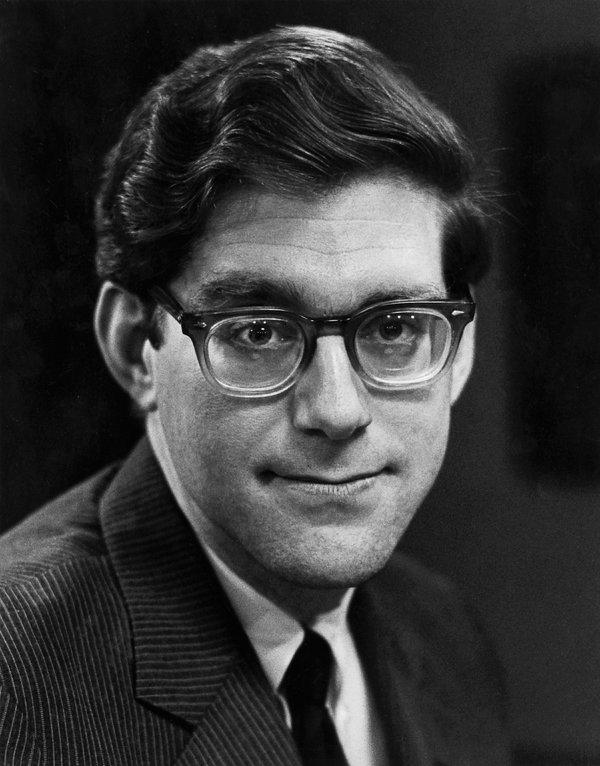

Mr. Pear in an undated photograph. For years he worked standing up at a specially built desk that he had gotten after undergoing back surgery.CreditThe New York Times

In the early 1990s, much to the White House’s consternation, Mr. Pear regularly pierced the cone of silence that the Clinton administration had erected around its negotiations for a national health care consensus. A number of White House allies even accused him of undermining the process by publishing leaks about incremental developments.

Many of his colleagues rallied to his defense, as did many medical professionals. In an email, Adam Liptak, The Times’s Supreme Court correspondent, said, “Robert knew as much about health care policy as any politician, official, congressional staffer or supposed expert, and he let them get away with nothing.”

Robert Lawrence Pear was born in Washington on June 12, 1949, to Philip and Marion (Kopel) Pear. His father was an accountant and tax lawyer; his mother had moved to Washington from Massachusetts during World War II to translate intercepted Japanese messages for the Office of Strategic Services. She later worked for the World Bank.

Growing up in the nation’s capital, Robert (never Bob) and his younger brother were under orders from their father to read the front page of the local newspapers before turning to the sports section. Gripped by President John F. Kennedy’s assassination when he was 14, Robert recorded every moment of television that weekend on a reel-to-reel tape recorder and collected an archive of newspaper coverage from across the country.

Fascinated with policy and politics and the personalities that drove them, he soon embraced journalism as the vehicle through which he could transform what one former colleague, the legal correspondent Fred P. Graham, described as his greatest strength — being nosy — into a career.

At Walter Johnson High School in Bethesda, Md., he edited the school yearbook and, as a social studies project, produced “The Pear Press,” a Times look-alike packed with coverage of historical events. Audaciously, he invited James Reston, the venerable Times columnist and Washington bureau chief, to lunch. Mr. Reston accepted.

After scoring perfect 800s on his math and verbal SATs, Mr. Pear enrolled at Harvard, where he joined the staff of The Advocate, the literary magazine. Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, who lived on the same floor freshman year, said Mr. Pear was so studious and polite that he was nicknamed “the deacon.” He graduated magna cum laude in 1971 with a bachelor’s degree in English history and literature.

Mr. Pear went on to earn a master of philosophy degree from Balliol College, Oxford, and a master’s from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

He spent five years at The Washington Star, which closed in 1981, before joining The Times. “Few American journalists,” said Ben Wakana, a former press secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services, “had more of an impact on the health care conversation than Robert.”

At The Times, the bureau’s newsroom was all but home to Mr. Pear.

“Not only did I make Robert go home several nights; I paid for a weeklong stay in Nassau in the Bahamas and carried him to the airport and put him on the plane,” Bill Kovach, a former Washington bureau chief, recalled. “He may have stayed there a day or two, but the next thing I knew he had slipped back into the office.”

That would explain how his byline appeared on more than 6,700 Times articles. Elisabeth Bumiller, the current Washington bureau chief, recalled that “the phrase ‘We have HEALTH by Pear’ was uttered hundreds of times in front-page meetings, to the relief of a generation of executive editors,” referring to the shorthand tag with which his proposed articles were named or, in newspaper parlance, slugged.

“In his memory we are retiring the slug HEALTH,” she said, “because it can only be by Pear.”