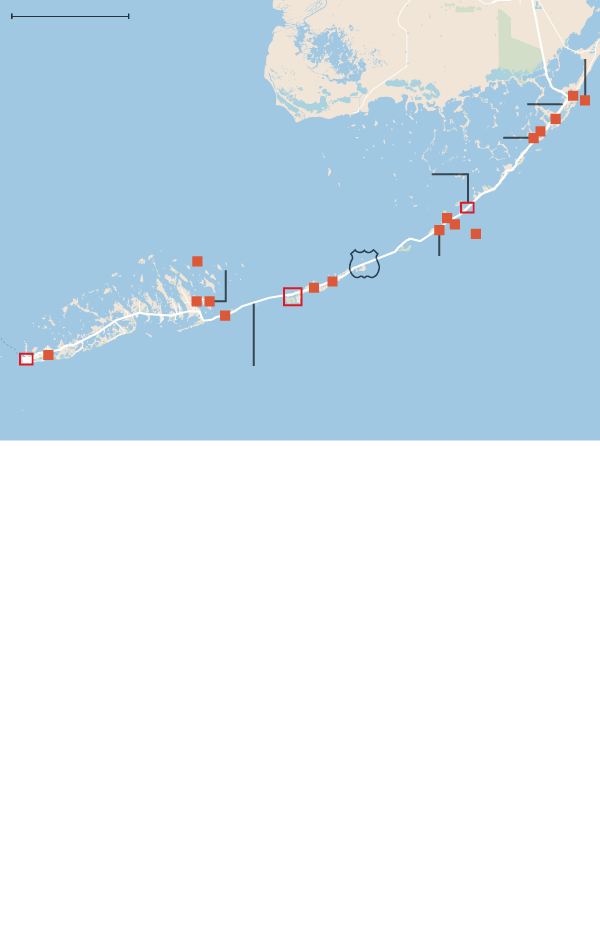

Seagulls and squadrons of brown pelicans flew alongside my rented Hyundai as I drove across the astonishing seven-mile stretch of U.S. Highway 1 that runs across Moser Sound, just south of Marathon, in the Florida Keys. The proximity of birds and water blurred the distinctions between sea and sky, drive and flight.

The string of coral islands that arc from the Florida peninsula south toward Havana has a long history of attracting pirates, profiteers and seekers of a Caribbean lifestyle within the United States. Henry Flagler, an early developer of the Florida Keys, inadvertently gave the country one of its most scenic roadways when his Overseas Railway, running from mainland Florida down to Key West, was destroyed in a 1935 hurricane. That land route eventually became the Overseas Highway, or U.S. 1, vaulting across channels, and linking 44 islands, via 42 bridges.

A fisherman near U.S. 1 in the Florida Keys.CreditScott McIntyre for The New York Times

I first drove the route with my sister in the early 1990s with a beer-filled cooler, tanning ambitions and the kind of dropout, sunbaked attitude that still drives the party crowd to the Keys, particularly Key West. The distractions along the way haven’t changed much. Local police and sheriff’s vehicles are still parked on the sides of the highway, jittery reminders that speed limits are strictly enforced. Cyclists share narrow shoulders over the 113-mile route from Key Largo to Key West. Manatee-shaped mailboxes, fishing marinas and seafood shacks proliferate. But most distracting are the views themselves, with the sparkling Atlantic to the left and the aquamarine Gulf of Mexico to the right as the road skips across scores of breezy, swim-inviting straits.

Over the course of repeated trips, I’ve come to appreciate the nature and wildlife of the Keys, home to endangered Key deer, mangrove forests and the only living barrier reef off the continental United States.

Hurricane Irma, which struck in September 2017 with Category-4 fury, threatened the delicate balance by which so many humans and animals exist amid the mangroves and bays. In November — 14 months and much cleanup later — I drove the route to assess the scars as well as the renewal, from recently opened (or about to open) resorts to a new coterie of mermaids.

Below is a guide to this classic coastal road trip. You could drive it in a single afternoon, but you won’t want to. Three languid days is more like it.

Upper Keys

Key Largo

From the rental car center at Miami International Airport, it’s just over an hour’s drive on mostly suburban highways to the Everglades bogs that edge Key Largo, the northernmost Key and the first to introduce visitors to both the natural attractions of the islands and Keys kitsch. At Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park, I stretched my legs in a native hardwood forest alongside bird-watchers who could identify a palm warbler just by its call, before hitting the bustling Fish House restaurant trimmed in strings of tiki- and flamingo-shaped lights.

Its proximity to Miami has made 18-mile-long Key Largo — a place where thick foliage obscures the water from the T-shirt and shell shops — attractive to developers eager to lure those who may not want to drive any farther down the highway.

“South Florida traffic is our bread and butter year-round,” said Herbert Spiegel, a consultant for the new Bungalows Key Largo, as he guided a tour of one of the island’s newest resorts, with its fleet of electric boats, a Himalayan salt room in the spa, four restaurants and bars, and an adults-only policy. “Florida is all about kids,” he added. “This is something different.” (And it doesn’t come cheap: all-inclusive rates at the resort, which opens this month, start at $1,300 per night, per couple).

Like the nearby Playa Largo Resort & Spa, the 135-cottage resort replaces a former R.V. campground, a trend that is nudging Key Largo upscale. But as the first stop nearest to the reef, it still attracts divers and ocean lovers across the economic spectrum to John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, where snorkeling tours explore the vibrant corals and the tropical fish they support in 70-square-miles of protected waters.

Islamorada

The everyday — in the form of schools, grocery stores and one very large Starbucks — mingled with signs for bird sanctuaries and state parks over the next 20 tropical miles from Key Largo to Islamorada. Spread across six lush islands, the community has an old-money heritage and a reputation as the sport fishing capital of the Keys, both of which came together in the bonefishing tournament that the late President George H.W. Bush ran for a decade from Cheeca Lodge & Spa, a vintage property with roots that go back to 1946. It’s no wonder the recent Netflix series “Bloodline,” a dark story built around a prominent Keys family, was based in affluent Islamorada.

The fictional Rayburn House inn from that series is the actual Blue Charlotte villa at the Moorings Village, where 18 rental cottages, some dating back to the mid-1930s, occupy a former coconut plantation. The hurricane denuded the property and killed its signature palm tree that bowed over the water.

“Not a blade of grass was left,” said Debbie Pribyl, the general manager of the Moorings, where the cottages have all been reroofed and the landscaping replanted. On this November day, three fashion photography crews were using the beach as a backdrop. “We got more sand than we started with.”

That ocean-side beach is private, but the two restaurants that the resort runs on the Gulf side aren’t. The casual Morada Bay Beach Cafe and the more refined Pierre’s draw nightly sunset crowds to tables set in the sand near speakers disguised to look like coral rocks emitting samba music as twilight paddleboarders stroke by.

Modest roadside inns, including the newly rebuilt Pines & Palms Resort with apartment-like rooms, eclectic restaurants like Midway Café and an arts district with a brewery and galleries contribute to Islamorada’s bohemian character. A new self-guided tour available via a free cellphone app from the history museum Florida Keys History & Discovery Center introduces hurricanes, pirates and island pioneers, winding up back at Cheeca Lodge where many of these original “Conchs” were buried.

Indian Key

To delve deepest into Keys history, Brad Bertelli, the curator of the Florida Keys History & Discovery Center told me, travelers have to leave the road at Islamorada, and become waterborne.

He and I launched rental kayaks from Robbie’s marina in Islamorada, a popular stop for feeding tarpon the size of teenagers, and headed for the offshore Indian Key Historic State Park. The 11-acre, mangrove-fringed island, with a shady tamarind grove and spiky sisal plants bordering the paths, holds the remains of a 19th-century wrecking village devoted to salvaging goods from ships that ran aground on the reef.

In the 1830s, Indian Key was the seat of Dade County, site of a bowling alley and an inn promising “one of the most favorable situations in the United States for persons who are suffering from pulmonary, dyspeptic and numerous chronic diseases, and obliged to seek refuge from the chill blasts of a northern winter,” according to a sign posted on the site. Prominent Keys travelers, including the ornithologist John James Audubon, passed through.

“Wreckers were thought of as the pirates of the day,” said Mr. Bertelli, looking the part with a bandana tied around his head. “Like used car salesmen, there were some bad apples.”

Today, the ghost of its town square is a large field surrounded by rock foundations of storehouses, cisterns and homes, eventually abandoned after the Second Seminole War in 1842. A three-story observation tower offers views to distant Alligator Lighthouse, marking the reef where the wreckers plied their trade, and, in the opposite direction, Lower Matacumbe Key, the source of fresh water, which allowed the island to flourish.

Middle Keys

Marathon

Another 30 miles south, past innumerable cormorants perching on power lines, and you enter another world. Lobster traps line the street to Keys Fisheries in Marathon, a commercial marina harboring fishing boats and pleasure sailboats, and a dockside restaurant where baby nurse sharks school in the shallows, waiting for scraps. The restaurant is an apt introduction to the working heartland of the Keys. Here, locals and those just passing through put in orders for lobster Reubens under superhero pseudonyms and wait to hear, “Captain Marvel, your order is ready.”

Commerce mingles with conservation in Marathon, home to two nonprofit marine attractions, the Dolphin Research Center and the Turtle Hospital. Both fund their operations largely through visitor tours.

Housed in a former motel painted sea green, the Turtle Hospital treats animals that are rehabilitating after swallowing so much plastic they can’t submerge, or have tumors growing around their eyes, a condition linked to water quality. Visitors see the operating room, the research lab and tanks filled with turtles ranging from hatchlings to 300-pound adults.

“It’s a very exciting time to be in sea turtle medicine,” said Bette Zirkelbach, the energetic manager of the Turtle Hospital on a tour, as she described a pioneering study in the lab on blood turtle types.

Nature-based tourism isn’t new to the Keys — snorkeling, diving and bird-watching are popular throughout the islands and, as I drove, a radio news broadcast urged listeners to use the “I Spy a Manatee” mobile app to both identify the animals’ locations and encourage safe boating around the slow-moving creatures. But getting travelers out of motorized fishing boats and into kayaks is relatively new on Marathon, where Miranda Murphy and Steve Tomek run three-year-old AquaVentures, which offers guided kayak tours in the tangled mangrove channels at Curry Hammock State Park.

As a naturalist, Ms. Murphy treats the waterways like living aquariums, pointing out schools of baby snapper and using a net to pull up starfish and jellyfish that illustrate the role of mangroves as nurseries of the sea. “It’s like a touch tank in the wild,” she said.

In March, AquaVentures will move its base of operations to the new 24-acre Isla Bella Beach Resort. Kayak tours of the mangrove tunnels in nearby Boot Key will take off from a canal at the resort where, on my visit, six manatees spent hours in the warm shallows.

Lower Keys

Bahia Honda

Seven Mile Bridge is the largest span in the Keys, and so exhilarating to cross that I returned another day to experience the drive in the blush light of dawn. It separates the Middle from the Lower Keys, and more commercial islands from some less developed ones, beginning with Bahia Honda Key, home to Bahia Honda State Park.

Beheaded palm trees and white sand beaches shorn of their shady sea grape trees testify to Bahia Honda’s location near the eye of Irma. This fall, one of its beaches reopened and snorkelers were trolling the shallows, but its popular Sandspur Beach, once lined with sea grapes decorated by visitors in seashells and driftwood, remains closed. Still, from the top of the old Bahia Honda Bridge, part of the original railway, there are hypnotic views across a 30-foot-deep channel that represented one of the most challenging to track-builders, sometimes limited by the tides to two 45-minute shifts a day.

Big Pine Key

Six miles west, much of Big Pine Key and neighboring No Name Key comprise the National Key Deer Refuge established in 1957 to protect the dwarf Key deer, an endangered subspecies of the North American white-tailed deer that grows just three feet tall. At the refuge visitors’ center, in a strip mall where a pair of free-ranging roosters foraged the parking lot, volunteers told tales of deer showing up beside a Winn Dixie grocery store dumpster, and extolled the resilience of the herd, which is now estimated to have between 500 and 800 deer. Many of the mangrove areas that edge their habitat remain barren after Irma.

Here, I met Bill Keogh, the easygoing owner of Big Pine Kayak Adventures, who guides paddling trips from Big Pine Key to the “backcountry,” a largely protected region of undeveloped mangrove islands. He still sees baby stingrays, snappers and sharks and, post-storm, a preponderance of lobsters on mangrove island fragments dispersed by the hurricane. “It’s the same biomass out there,” he said, “but it’s concentrated in new real estate.”

Leaving him at sunset, I crossed a bridge to No Name Key to look for deer, which I found not only there — collie-sized critters galloping across the sandy road — but, on my return to the highway, where I stopped to watch an elfin stag, doe and fawn grazing a town lawn.

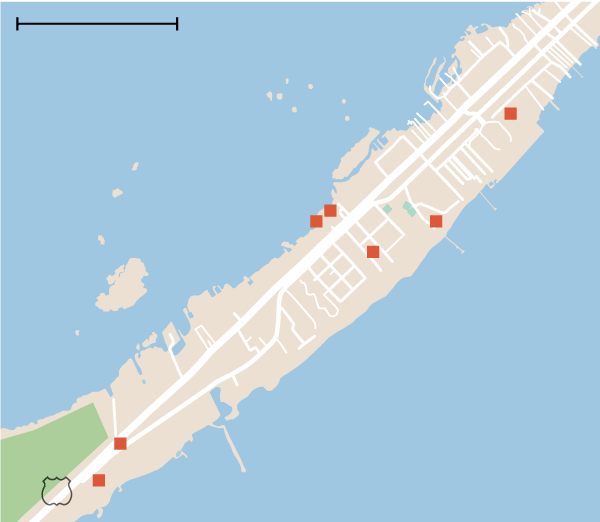

Stock Island

After 25 quiet miles crossing calm bays with views to distant patches of mangrove isles, I reached the outskirts of the city of Key West on Stock Island, a traditionally blue-collar refuge for shrimpers, commercial fishermen and tourism industry employees. With its mobile homes and canals moored with houseboats, it retains a grittiness that its more manicured neighbor, the island of Key West, has largely lost. But it, too, is experiencing development, now mingling marinas, newly paved streets and bushy bougainvillea with a pair of new resorts including the Perry Hotel Key West.

With art installations made of propellers, the 100-room hotel facing a recreational marina nods to the shrimp-trawling boats across the channel. Its main restaurant, Matt’s Stock Island Kitchen & Bar, has become a dining destination for upscale versions of local seafood, such as black grouper with cornbread gnudi and crawfish-thyme butter, recommended by my Russian waitress who said she came to the Keys on vacation and has stayed seven years.

“The islands got me,” she laughed.

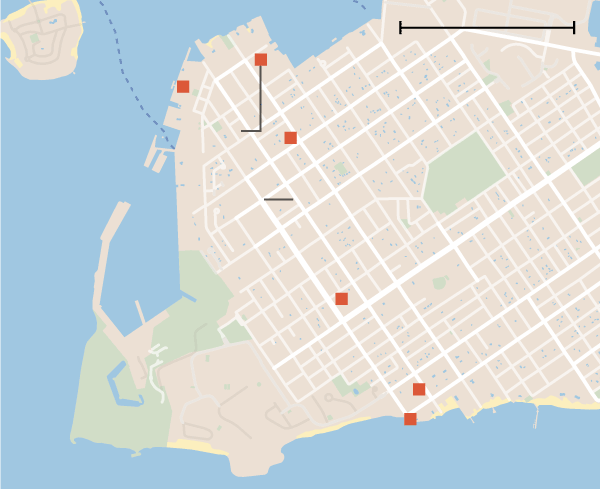

Key West

The next day, the Perry’s free 15-minute shuttle dropped me in teeming downtown, tourist-thronged Key West, the end of U.S. 1 and home to harbor-front bars and souvenir shops with a prevalence of mermaid ornaments, statues and paintings. In this setting, the Captain’s Mermaid boutique owned by Kristiann Mills, a native Conch who identifies as a mermaid, is a tranquil, if glittery, refuge. She explained that many of her mermaid “pod” teach “mermaiding,” or swimming in a long tailfin, and that she is launching the first Key West Mermaid Festival, July 5 to 7, to draw attention to conservation.

“We’re a little angry the ocean’s being polluted and we’re coming on land to tell you about it,” said Ms. Mills, with the warm smile and flowing hair you might expect of a mermaid.

Home of the Conch Republic, which tried to secede from the union in 1982, Key West has long attracted nonconformists, artists and especially writers, from Ernest Hemingway — whose former house-turned-museum is famously filled with descendants of his six-toed cat Snow White — to Judy Blume, who co-founded Books & Books @ the Studios of Key West, a bookstore within a nonprofit gallery just blocks from the bar-lined Duval Street.

“Duval is a tiny Bourbon Street,” said Shannon McRae, the general manager of Key West Food Tours, over a Hemingway daiquiri off Duval on her company’s new Craft Cocktail Crawl. The three-hour tour visits dives as well as chic lounges. “We want to surprise you and let you drink like a local.”

Key West, a village of tidy bungalows and Victorian captain’s homes, offers much more than bars, of course, and it isn’t hard to escape the rowdies on neighborhood walks or in attractions like the Key West Butterfly & Nature Conservatory, a calming sanctuary of blue morphos, pointed leafwings and dusky swallowtails.

Around the corner, selfie-takers lined up at an oversize buoy marking the Southernmost Point of the continental United States, painted with an arrow indicating “90 miles to Cuba.” Many came from cruise ships to get their Instagram shot. Cruise traffic is growing on Key West, where 405 calls are expected in 2019 versus 307 in 2016.

Many ships sail out before sunset, which is a shame as sundown cues a carnivalesque celebration nightly at seafront Mallory Square that’s both a tribute to nature and a showcase for quirky characters who make their living in Key West. At one end of the seafront strip, I watched a ringmaster run house cats through hoops like circus felines; on the other end a contortionist quipped, in the outsider’s humor so common to the Keys, “I call this an economic recovery. It’s an illusion.”

Elaine Glusac is a frequent contributor to the Travel section.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.