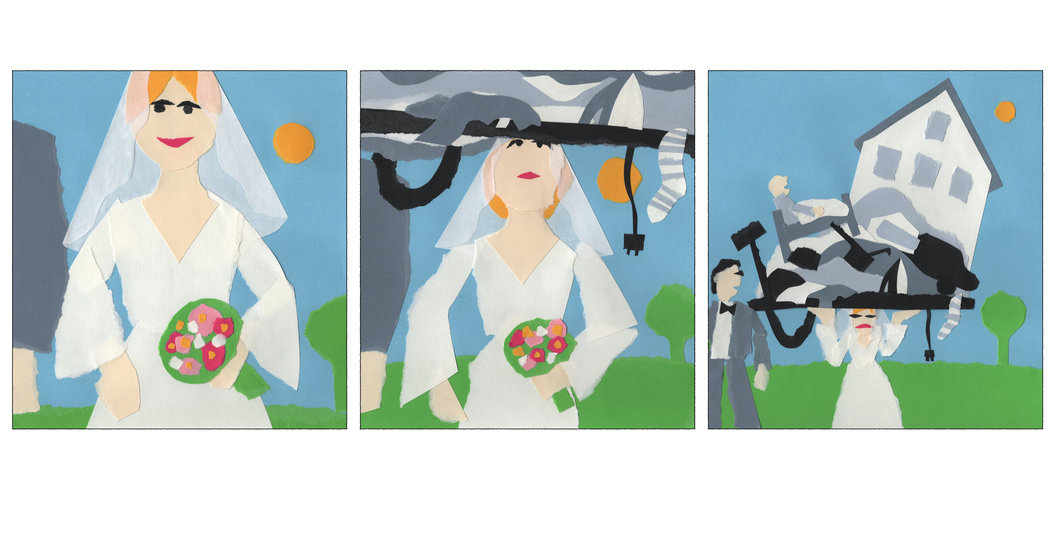

My mother, in an effort to keep me humble and rooted, likes to remind me of embarrassing facts from my childhood. Her favorite one lately: I marched up and down the hallway belting out “Here Comes the Bride” with a sheer beige curtain over my head as a veil. If anyone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, my 5-year-old voice proudly said, “a bride.”

When my older sister overheard this, she said, “You can only be a bride for a day, idiot. What do you want to do with your life?”

I thought about it briefly and corrected my answer: “A wife. I want to be a wife.”

In my mind, the image remained the same: a radiant woman, front and center, dressed in full bridal plumage. Only a vague sense of a spouse entered this fantasy. A hazy outline of a man, wearing a tuxedo, hovered in the background like a waiter ready to fill my water glass. The idea that a bride, or wife, requires another person to define it never occurred to my childhood mind. A bride is a starring role.

Not so much, I realized much later, as a wife.

When I met my future husband in my mid-20s, I had long forgotten my childhood fantasy. Both of us were anti-marriage. Products of bad divorces, we bonded over our aversion to the concept. Late at night in bed, postcoital, eating toasted baguettes with butter and feta cheese on top, we talked and mocked that worn-out, passé ritual.

“Here’s the deal,” I said, swallowing a bite of bread. “If either of us is unhappy or unsatisfied in this relationship, we can leave. It’s that simple.”

“We only stay because we want to be here,” he said. “Not because of some ancient ceremony sworn in front of a hundred relatives we hardly know.”

Having settled that, we had sex again.

[Want more coverage of women and gender issues? Sign up for Gender Letter, a weekly newsletter, or follow us on Instagram @nytgender.]

Three years later, when I was pregnant with our first child, my mother pressured us to marry. We resisted. Still, we stopped using the breezy measure of happiness as a basis for commitment.

After our second child was born, instead of discussing marriage, we joked: “If you want to leave, go right ahead, but you have to take the kids with you. That’s right, take the barfy, snotty, wailing children with you. Enjoy your single life!”

We lumbered through the next few years broke, in law school, and raising toddlers until my mother-in-law died suddenly from cancer. Under stress and bereavement, both of us felt a desperate need to celebrate something. Anything.

“We could get married?” he said, hesitantly, one night after we’d put the children to bed. He stood next to the sink with tea towel thrown over his shoulder.

“What about a commitment ceremony?” I said, scrubbing a stained pot.

“But then we’d have to get a lawyer to draw up documents to have the same rights as married people,” he said. “It’s easier to get married. It’s like an all in one.”

“I don’t know,” I said. I balanced the dripping pot on the dish rack. He picked it up and began drying.

“You should have the protection of marriage,” he said. “Besides, it’s cheaper.”

And with those words of romance, we decided to get married.

After the wedding, something happened that surprised me. He introduced me as his wife. Of course he did. I don’t know why this startled me so much, but each time he said it I shrunk inside. A coil inside me tightened. Noticing my reaction when we were out one night with friends, he asked me on our way home why I had such a physical reaction to the word.

“I hate it,” I said. “It’s like you’re talking about someone else. Not me.”

“But I like calling you my wife.”

“Can we use something else?”

“Like what?”

“Partner.”

“It’s sounds too economic. Or like we’re in a Western movie.”

“You can say, ‘That there’s my pard’ner. She dun gun sling with the best of ’em.”

“You want me to use a weird accent every time I introduce you?”

I don’t want to be introduced at all, as anything other than my name, I thought, but I did not say this out loud.

For years he went along with it (without the accent) and called me his partner or spouse. But eventually, after five or six years of parent-teacher interviews, silent auctions and cocktail parties, I gave up and said, “Forget it, just call me wife. It doesn’t matter.”

Beware these warning signs in a relationship, when compromise becomes defeat. I gave up on something that mattered to me.

A subtle shift occurred during these years. As a wife, I cleaned more toilets, arranged more dinners and social events, laundered more clothes, paid more bills, picked up more socks off the counter than my previous unmarried self. I even bought an iron — and I’d never ironed anything in my life. These tasks, things under the rubric of “what wives do,” became chores I resented, yet also felt fiercely territorial over, as if they gave me value and worth.

Ultimately “wife” was a role that I cast myself in and then tried to make fit. Rarely, if ever, did I communicate this internal tension to my husband.

Last fall, I met with my lawyer to hash out a separation agreement. After 18 years together, we were separating. Two children, two cities, four degrees, four homes, five cars, one cat, one dog and six hamsters later, we began the process of untangling our lives. From wife to ex-wife.

I am the third generation of divorced women on my mother’s side. Does it run in the family? A genetic flaw? The idea of marriage for me has its demise, divorce, built in. The understanding of wife is one I inherited, and despite all my efforts I was not able to transcend or redefine it for myself.

Would my husband and I have stayed together had we not married? Likely not. The problems in our relationship existed from the beginning. One recurring disagreement stays with me. We had this fight many times, but the version I carry around in my mind now and replay at various times when I doubt myself occurred at a restaurant about a year before we separated.

“You have no ability to collaborate,” he had said. It was our date night, or what had functionally become fight night. “Do you know how frustrating that is?”

I lowered my voice so the table beside us couldn’t hear. “What do you mean?” I said. “I compromise all the time.”

“I’m talking about working together to make decisions, instead of one of us making a decision and the other one putting up with it,” he said.

“But we talk about decisions all the time,” I said. “We talk and we talk and we talk.”

“You don’t get it,” he said, refolding his napkin. The candle flickered between us from the force of his breath and then stilled. Neither of us said anything for a long time.

When we got home, I looked the damn word up. Collaboration. Yes, yes, I understood correctly: the “action of working with someone to produce or create something.” That’s what I thought I was doing.

But it doesn’t matter what I thought because if there isn’t a shared understanding of a concept between two people — “collaboration,” “marriage,” “husband,” “wife” — then language fails. And maybe he was right. I didn’t get it because collaboration assumed a person, a whole self, rather than someone who feverishly, with distressed eagerness, struggled to maintain a role.

The confines of wifedom fall away quickly.

Unexpected habits return; I bike around the city again. Shopping at thrift stores, like I did in my early 20s, has become a Saturday thrill. I don’t have the same compulsion to get things done. At night, I lie on the couch in front of a fire and, like my dog, watch people walk down the street. Hours go by, pleasantly doing nothing.

Is this depression? Contemplation? Loneliness? Time spent in my own company for no purpose whatsoever. I don’t have a word or label for it. What do we call a woman who places herself at the center of her life? We have no language for this.

One Saturday afternoon, when my children were with their father, I found my old wedding dress in the back of my closet, still in its original garment bag, still with a wine stain from the reception. I quickly undressed and slipped it over my head. Like a gothic bride or a ghost, I drifted through my house paying bills, then later scrambling eggs for dinner dressed in this full-length champagne silk gown.

I don’t want to be a bride anymore when I grow up, but every now and then I still like to dress like one.

Marcia Walker, who teaches creative writing classes at the University of Guelph in Canada and online at One Lit Place, is working on a novel and a collection of short stories.

Rites of Passage is a project of Styles and The Times Gender Initiative. For information on how to submit an essay, click here.