Of all the curses confronting an artist, the most ominous may be to have been ahead of one’s time.

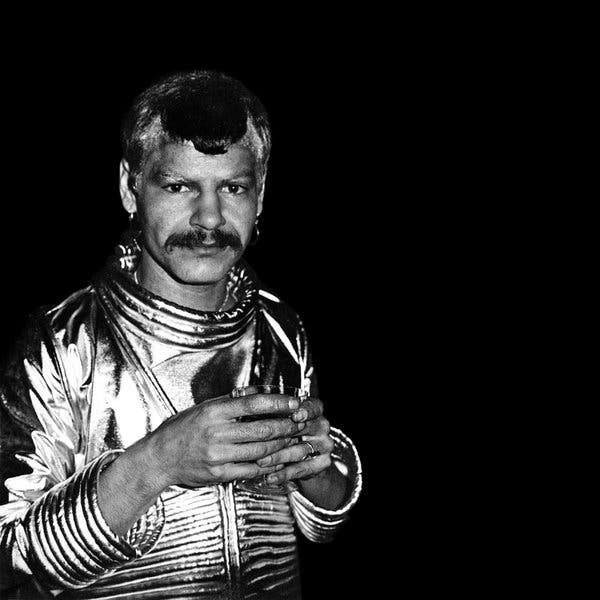

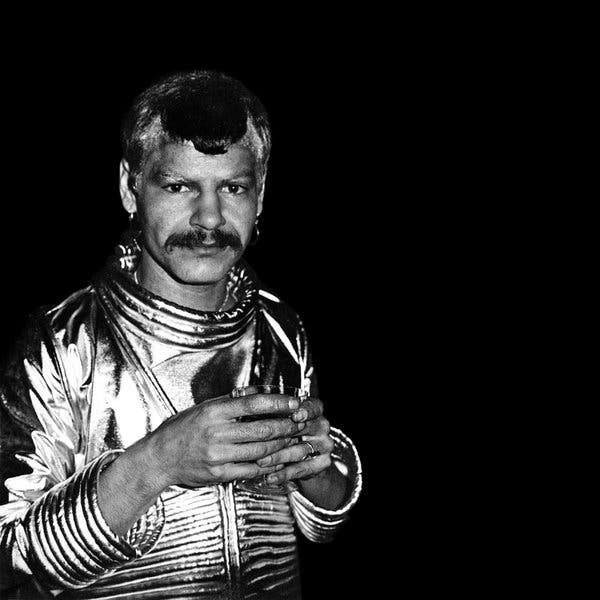

Such was the case of Larry LeGaspi, a gifted and largely self-taught designer whose wacko space age creations of the 1970s were inspired equally by Fritz Lang and the proto-feminist comic book character Katy Keene.

Sold originally at Moonstone, a small boutique in downtown Manhattan, LeGaspi’s designs were eventually adopted by some of the defining musical acts of the era, first as stage wear by the all-female group Labelle at their hit-making peak and afterward by Grace Jones, George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic.

It was LeGaspi as much as any other person who deserves credit for the look of the arena rock megastars Kiss.

While others designers (Claude Montana comes to mind) drew what could politely be termed inspiration from LeGaspi’s metallic disco futurism and forged booming careers, his own trajectory was tragic. By the time he died of AIDS in 2001, LeGaspi was broke and forgotten and dumpster diving in Los Angeles. Determined to rescue a figure he considered a hero from unfair obscurity, Rick Owens set out some years back to write a book about LeGaspi.

The resulting monograph, “LeGaspi,” a deeply eccentric amalgam of homage, personal memoir and reminiscences by people like the Kiss vocalist Paul Stanley, the actor Juan Fernandez and the model Pat Cleveland, has just been published.

Recently Mr. Owens spoke about the project by phone from Paris, where he lives. (The interview has been edited and condensed.)

This book is unabashedly as much autobiography as homage. You even characterize it as a biography filtered through the lens of you as “a 15-year-old sissy” observing the power that marginalized communities can exert on the mainstream. Can you talk about that evolution?

It’s been a gradual thing. By the time I was listening to Labelle in the ’90s, I was conscious of how important the Larry LeGaspi look was to me. It was only in the 2000s that I realized that this was the person who was responsible for Kiss.

And 20 years later that revelation became a book?

What happened is I mentioned LeGaspi in an interview, and his widow reached out through a group of friends. I think I was already talking about doing a book when she contacted me. When she reached out, I said I’m probably going to do this book, but, as just a warning, you should know it’s going to be more about me than about Larry.

How so?

It’s my own personal edit, so it’s not the full spectrum of who he was and what he did. I approached people who might not have been primary people in his life, and to be truthful, once I put the book together, I felt a twinge of guilt. In a sense, it’s about him, but not about who he was.

You mean biography as emotional collage?

If you’re being as honest as you can be, you realize that when you’re making anything, you’re having a conversation with people. I try not to make that process totally egocentric.

That’s an interesting ethos, but how did it affect the making of this book?

What I’m talking about with the book is my perceptions of LeGaspi at a given moment, of the things he created and that whole period as I saw it from my remote perch in Porterville, California.

To begin with, you have black soul culture in the form of Labelle. The fact that Larry infiltrated that was already a huge thing to me. Then you have the merging of black soul culture and middle-American testosterone rock, this black-and-silver camp sensibility that became part of the arena rock phenomenon. None of that makes any sense. But it all happened, and it worked.

It bears some resemblance to your own trajectory.

What interests me is the scope of what happened with Larry, of all those aesthetics combining. It is really a wonderful thing to contemplate, especially in today’s age, which seems pretty safe and pretty banal most of the time.

I was talking recently about contemporary aesthetics and how 20 years ago we were still impressed with fabric being put together in certain ways and how craft has become something quaint. I don’t know that that’s a bad thing, but I do know that the aesthetic of the moment is about shrewdness and cynicism. Cynicism is seen as sexy.

There is no question that the corporatization of fashion and the careerism on social media feel pretty far from the innocence — you might say cluelessness — of New York in the 1970s.

There does seem to have been some urgency then that propelled these people to throw themselves into something almost recklessly and that looks so appealing from where we are now. The part of the book that continued to thrill me, to tell the truth, was that this guy with this camp kind of approach infiltrated Middle America with Kiss. And it was embraced by this world of testosterone and swagger, and I love where it came from. I love reminding people ——

Of what? That there was this small group of creative gay men who stealthily — and maybe also inadvertently — subverted straight culture?

For me it connects to the oppression of my childhood and being judged by a conservative town and how that filled me with rage and made me want to defy them. I still feel that rage.

But you channeled that rage into an exceptional career, whereas Larry LeGaspi is virtually unknown.

Well, he died.

Is there an element, then, of this project as historical recuperation? It was not just LeGaspi. Most people in his circle also died.

For me personally, I wasn’t circulating that much in those days. I wasn’t part of that community. I wasn’t going to the funerals. My emergence culturally or socially happened afterward, and so even though I’m talking in a way about the impact of AIDS, I’m afraid I don’t have the authority to talk about it.

I’m not sure I agree.

There are so many people to remember. They aren’t necessarily people I know about — I never met Larry, either — but I was connecting with the aesthetic they created from the moment I started to be aesthetically conscious.

To tell you the truth, I was not about memorializing one person. That might be the whole point of this book, that there is the possibility for that kind of sensibility to infiltrate Middle America. There’s a wonderful sense of hope in that.

Is there also an element of nostalgia?

I think I am nostalgic. I’m not paying much attention to contemporary culture right now. All I do these days is read autobiographies from the 1930s. I like to look back and see how somebody maintained a standard all the way through life.

You can’t say that of the way most people are doing things now. But remember that this is also the story of other people, people like Juan Fernandez and Pat Cleveland, who were so immersed in that world and survived it.

Their voices, their reminiscences of Larry and Salvador Dalí and of the gay dance club the Tenth Floor, and of Amanda Lear and of the mixing that went on across boundaries of class, race and gender, add an almost elegiac tone to the project.

I always knew there was going to be an air of melancholy to the book.

Yet it remains hopeful.

The world benefited so much from the energy of these people.

Though Larry died broke and living out of dumpsters.

Ultimately whatever money you earn in life is not going to make that big a difference. But every single person wants to be listened to and remembered.

I’m not sure I follow you here.

Larry becoming a part of history is the best outcome. He’s on Wikipedia now. That was our biggest triumph.

So, in a way, this book is equal parts homage and reparation.

For the children now, Larry and his friends are the basis of their history and their freedom. He is how we got where we are today. Part of what this project is about is remembering the amazing people that passed away and didn’t get a chance to fulfill their destinies. How can we let these people be forgotten? The children need to know.