Deep into the third hour of testimony in federal bankruptcy court by Dr. Richard Sackler, a former president and co-chairman of the board of directors of Purdue Pharma, a prescription opioid manufacturer founded by Sackler family members, a lawyer posed a chain of questions:

“Do you have any responsibility for the opioid crisis in the United States?”

“No,” Dr. Sackler, 76, replied faintly.

“Does the Sackler family have any responsibility for the opioid crisis in the United States?”

Again, “No.”

And finally:

“Does Purdue Pharma have any responsibility for the opioid crisis in the United States?”

More firmly: “No.”

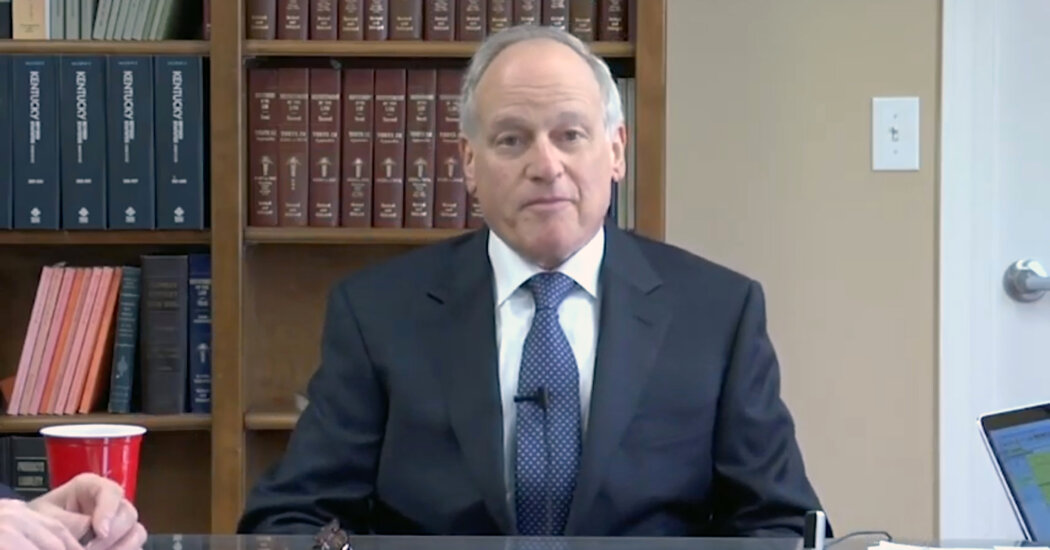

Dr. Sackler, perhaps the best-known among the billionaire Sacklers, who for nearly 20 years was the family member who figured most prominently in the company’s rollout of its signature prescription painkiller, OxyContin, made a rare, protracted appearance by video conference on Wednesday before a judge presiding over the confirmation hearing for a plan that would restructure Purdue and settle all lawsuits against the company and family members for their role in the opioid epidemic.

It is believed to be the first time that Dr. Sackler has answered questions in open court about the family’s opioid business. Similar to an extended deposition he gave in 2015 to Kentucky state lawyers, Dr. Sackler offered testimony largely pocked with faint or absent recollections, terse statements and deflections to his legal team.

His voice often scarcely audible, he apologized for having laryngitis and appeared occasionally to fumble with the technology, which presented vexing challenges in volume level and in the opening of documents emailed to him as he testified.

Nonetheless, although he did not offer fresh insights into what is already on the record about Sackler family members’ roles in the company, his appearance was notable for what he refused to acknowledge.

Dr. Sackler had been called to appear for questioning by lawyers for states that oppose the plan, in part because they think that the Sacklers, in exchange for paying $4.5 billion, will receive legal protections that are too broad.

In a biting back-and-forth, Dr. Sackler said he did not know how many Americans had died from OxyContin. “You didn’t think it was necessary in your role as a chair or president of an opioid company to determine how many people had died as a result of the use of that product?” asked Brian Edmunds, a Maryland assistant attorney general.

“To the best of my knowledge, recollection, that data is not available,” replied Dr. Sackler.

Dr. Sackler — who trained as an internist but embraced a career as a pharmaceutical executive for the Stamford, Conn.-based company originally overseen in part by his father, Dr. Raymond Sackler — is known for having thrown himself into Purdue’s operations. In testimony on Wednesday, Dr. Sackler described riding along with a Purdue sales representative on calls to doctors to beef up sales. The sales staff eventually came to focus its efforts on doctors who were inclined to prescribe higher doses, Dr. Sackler said. He acknowledged that higher-dose opioids could lead to greater profits for the company.

During his tenure, Purdue pleaded guilty twice to federal criminal charges related to marketing and sales of OxyContin and struck a deal for a settlement with Kentucky.

Lawsuits against the Sacklers and Purdue have quoted numerous emails written by Dr. Sackler, including one from 2001, cited in a complaint by Massachusetts. “We have to hammer on abusers in every way possible,” he wrote. “They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

In 2019 the Sackler family contributed $75 million to Oklahoma as part of a larger settlement between the state and Purdue. In that case, as in a 2020 federal civil settlement with the Sacklers, family members made no admissions of wrongdoing.

“I cannot count up all the settlements,” Dr. Sackler said. “There were many settlements, both private and public.”

The lawyers from Maryland, Washington State and Connecticut were apparently seeking to extract such shards to reassemble for an argument that the Sacklers were deeply involved in the business of Purdue.

The settlement deal negotiated by Purdue and the Sacklers with states, tribes, local governments and other claimants would not only settle the lawsuits but would grant the company immunity from future civil legal claims, a condition commonly conferred on companies that emerge from bankruptcy restructuring.

But this plan would also give a similar shield to the Sacklers, who have not filed for bankruptcy. The issue of such expansive legal protection for the Sacklers is what has driven many of the remaining objections to the plan.

If the plan is confirmed by Judge Robert Drain of U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York in White Plains, as is expected, the Sacklers cannot be pursued by those who object to the plan, much less any future litigants, for any Purdue-related matters.

And that prohibition is not merely confined to opioid-associated cases. Benjamin Higgins, a lawyer for the U.S. Trustee Program, a unit of the Justice Department that monitors bankruptcy cases, noted that Purdue, for example, had in recent years introduced a long-acting stimulant medication to address symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and that if any lawsuits were contemplated in connection to that drug, the Sacklers would be immunized from them as well.

Dr. Sackler said he was not very familiar with the details of the extensive releases from litigation that are at the core of the Purdue bankruptcy plan.

“It is an extremely dense document,” Dr. Sackler said. “I read a page or two and realized it would take me an enormous amount of time.”

According to the complex structure of the Sackler payments to a national opioid abatement trust, the contributions will be financed in part by what is expected to be the sale of the family members’ diverse pharmaceutical companies worldwide.

“Are you going to be personally contributing any of your own assets to the settlement payments over the next nine or 10 years?” Dr. Sackler was asked.

“I don’t know,” he replied. “I don’t believe that’s been decided yet.”