Jean-Michel Basquiat liked his clothes the way he liked his art: “oversized, off-kilter, chaos in control.” His paint-stained, joint-burned outfits were highly crafted, and often expensive — he favored the designs of Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Garçons — but they never lost the spirit of his former homelessness: “Always dress just in case,” he’d say. “I might have to sleep on the street.”

In WHAT ARTISTS WEAR (Norton, $30), the British fashion journalist and art curator Charlie Porter treats his subjects as more than just “style icons.” Making art can be isolating, dispiriting, consuming, he says. What a person wears while doing it, whether a smock or blue jeans or couture, is “a testament to this fearlessness, this focus.”

It’s also a testament to their humanity: a response to the canon of deified white men, a reminder that all artists are mere mortals with bodies that need covering just like ours. What adorns the nonmale (Louise Bourgeois, Mary Manning), nonwhite (Tehching Hsieh, Alvaro Barrington) bodies in this book is as much self-expression as resistance.

“What can these artists tell us about how we all wear clothes,” Porter asks, “all of us who try to pretend we’re not performing, all of the time?”

At the Area party for Keith Haring’s new POP shop in New York City in 1986, Basquiat’s look is pure instinct, and aesthetic: the shirt and trousers of mismatched plaid, underneath a slouchy jacket (probably Comme des Garçons) and a hat by Kazou. The juxtaposition makes the artist Francisco Clemente, to his right, look more like an accountant, in his stiff, starchy-looking suit and tie.

“Attack clothes,” Cindy Sherman scrawled in her notebook in 1983: “ugly person (face/body) vs fashionable clothes.” The same year, she published a series of self-portraits in Interview magazine that “questioned fashion imagery,” Porter writes, including this photograph in which she wears a tailored, imperfectly-fitted jacket-dress (who can say which?) by the French couturier Jean-Paul Gaultier. Rather than fetishizing the garments she wears as pieces of art in themselves, she sees them as only “a means to an end.”

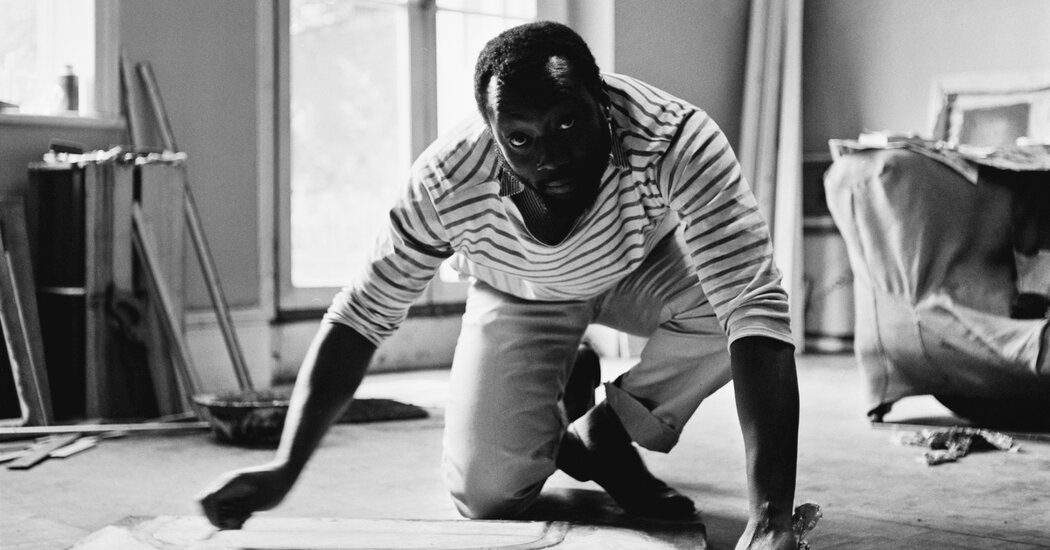

At 25, David Hammons made his first of many body prints, which brought his name into the public consciousness. It was 1968 and he’d moved to L.A. from Springfield, Ill., five years earlier. Bruce Talamon photographed him in his studio in 1974, wearing jeans and no shirt, a bottle of baby oil to his right. “He has just poured the oil on his hands and is rubbing them together,” Talamon told Porter. “He would then rub his oily hands on any part of his body and also onto his clothes and then press that body part onto the paper.”

Like a baby’s foot or hand print in a family scrapbook, the result was a record, a preservation, of a person and a moment that would inevitably change with time. “By doing body prints,” Hammons said, “it’s telling me exactly who I am and who we are.”

The German Fluxus artist Joseph Beuys was photographed by Caroline Tisdall at the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland in 1974, wearing his later-life uniform — white shirt and jeans, fisherman’s jacket, felt hat — beneath a fur-lined coat. According to Porter, the uniform “made him one of the most recognizable artists of the 20th Century.” But for him, clothing was not simply a “trademark”: Each of these components was both function and personal mythology. The hat, for instance, he wore to protect his head from the cold after a plane crash (in 1944, when he was in the German Air Force) left him with a metal plate in his skull. According to his shamanistic beliefs, he said the hat “represents another kind of head and functions like another personality.”

Lauren Christensen is an editor at the Book Review.