LONDON — Mary Quant was one of the best-known designers of the Swinging Sixties, a creative and commercial trailblazer who put London fashion on the world map. Synonymous with some of the defining styles of the era such as the miniskirt and hot pants, she helped spark a quantum shift in fashion, pushing the boundaries of acceptable streetwear and challenging the dominance of male French couturiers.

Yet today, the 89-year-old plays second fiddle to many of those better known industry greats.

Now a new exhibition on her life and work, opening April 6 at the Victoria & Albert Museum, aims to rectify that situation. The first international retrospective of her work in almost half a century (the last one was in 1973 at Kensington Palace in London), it focuses on her heyday from 1955 to 1975, with more than 120 garments on display over two floors, along with accessories, cosmetics, sketches and photographs belonging to Ms. Quant, most of which have never been seen before.

“Mary Quant grew up at a time when women were meant to dress like their mothers and went straight out of [school] uniform into pearls and twin sets, particularly in Britain,” Jenny Lister, the exhibition co-curator, said. “With her higher-than-high hemlines, colorful tights and masculine tailored trousers, she helped wipe out British postwar drabness and create a bold new attitude to dressing.

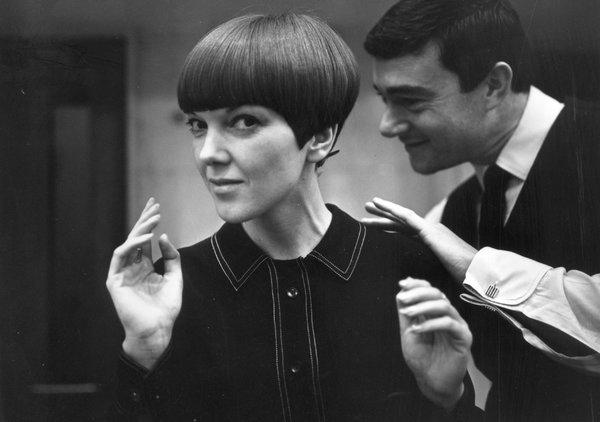

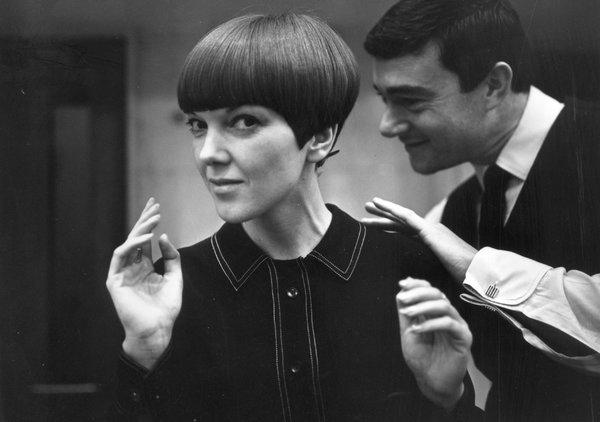

Ms. Quant with the hairstylist Vidal Sassoon, another ‘60s celebrity. The designer’s sculpted bob was an important part of her public image.

“More than that, as one of the earliest and most eminent female fashion designers, Mary was also a powerful role model for working women,” she added.

Emerging at the time of feminism’s second-wave (after suffrage), Ms. Quant famously said she “didn’t have time to wait for women’s lib.” The exhibition — ranging from the boxy clothes she created for Bazaar, which opened in 1955 as the first boutique on King’s Road (later, the epicenter of ’60s fashion) to some of the thousands of her products that were licensed, mass manufactured and sold around the world — suggests she had an approach to the business of fashion and branding that was far ahead of her time.

Her practical stretchy jersey dresses, pinafores with Peter Pan collars, PVC raincoats and flat shoes are showcased against a backdrop of vibrant Pop Art illustrations. So, too, are the tools she used to propel herself to fame, including her distinctive daisy logo, adventurous approaches to advertising and her personal style (symbolized by short skirts and a Vidal Sassoon-sculpted bob).

“The celebrity designer is an accepted part of the modern fashion system today, but Mary was rare in the ’60s as a brand ambassador for her own clothes and brand,” Ms. Lister said. “She didn’t just sell quirky British cool, she actually was quirky British cool, and the ultimate Chelsea girl.”

The Quant lifestyle empire later encompassed numerous international licenses, including stationery, paint, kitchenware and cosmetics. And, although the exhibition stops in 1975, Ms. Quant did not, going on to author books about her makeup ideas, introduce a limited edition of the Quant Mini car, and open a chain of Mary Quant Colour shops in Japan.

In 2000, she resigned from the company that bore her name, selling it to her Japanese license holders in a deal cloaked in secrecy. She has kept a relatively low profile since then.

What the exhibition underscores is just how much she influenced today’s fashion — some exhibits look as if they came right off the fall runways — and also the impact she had on women’s lives. Indeed, a montage of video and images featuring some of the hundreds of women who responded to the museum’s call out last year under the hashtag #wewantquant, displayed in the show’s upper pavilion, leaves visitors with a renewed sense of the power of Ms. Quant’s name and legacy. Conceived as a way to track down some of the designer’s pieces now in private closets, it became a trove of memories as women described how they bought her clothes to wear to job interviews, birthday parties, work presentations and weddings; how they wore miniskirts to drive mo-peds through their mill hometowns or to present their university theses.

Ms. Quant did not attend previews of the show, but Ms. Lister said she supported the concept.

“The whole point of fashion is to make fashionable clothes available to everyone,” the designer once declared in 1966. By any measure, this retrospective suggests that Ms. Quant — a committed pioneer of feminism and democracy in the industry — did exactly that.

The exhibition “Mary Quant” runs to Feb. 16, 2020. vam.ac.uk.