“I hope to be around for a long time,” my father said, “but I’ve written my funeral plan so we’re all prepared.”

That morning, he’d cycled to the farm in Fairhope, Ala., where he volunteered in exchange for organic vegetables. My dad was 62 but could pedal faster than his four middle-aged kids. He had gathered us at our childhood home to share his goal of having a burial that relied on family and friends, not a funeral home.

After almost four decades of marriage, he was learning to live alone. Dad had lost his cycling partner when my mom was hit and killed by a teenage driver while biking to the same farm the month before. My father, a retired IBM salesman, wanted to make sure he — and we — were prepared for his death when the time came.

“First I’d like my body to rest in the bed under Mom’s quilt for four hours,” he said. “Then you can wrap me in linen tablecloths as a shroud and place me inside the casket. I’ve talked to my friend Jeff who’ll build my pine casket if I can’t do it myself.”

With smile lines etched on his cheeks, Dad reminded us that embalming — or “filling a dead body with chemicals” — wasn’t required by state law, as long as the burial happened in three days. He knew that his cemetery contract didn’t require a concrete vault.

Dad wanted to have plenty of shovels so old and young could fill the grave with soil. And he’d written a playlist for his bluegrass gospel band, starting slowly with “Amazing Grace” and ending with the upbeat rhythms of “I’ll Fly Away.”

The level of detail felt suffocating. At 38 years old, I wasn’t ready to plan for his death, not when I needed him as a grandparent for my children.

I was still adjusting to his daily phone calls, and the crumbs on his kitchen counter my mom would have wiped clean in a heartbeat. After supper, he’d invite us to play cards, a proxy for my parents’ nightly game of rummy to decide who had dish duty. He counted cards. She didn’t. And of course, she usually won.

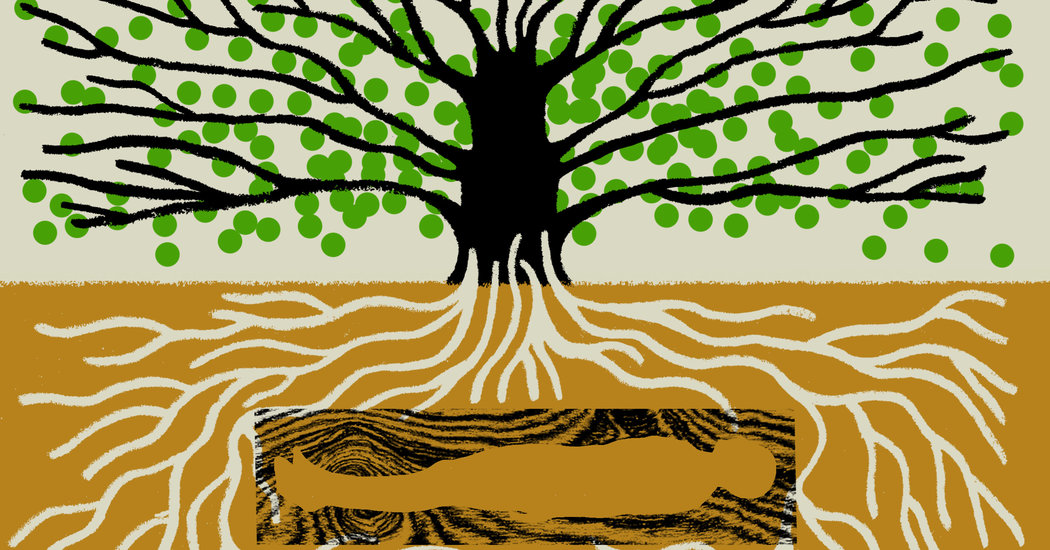

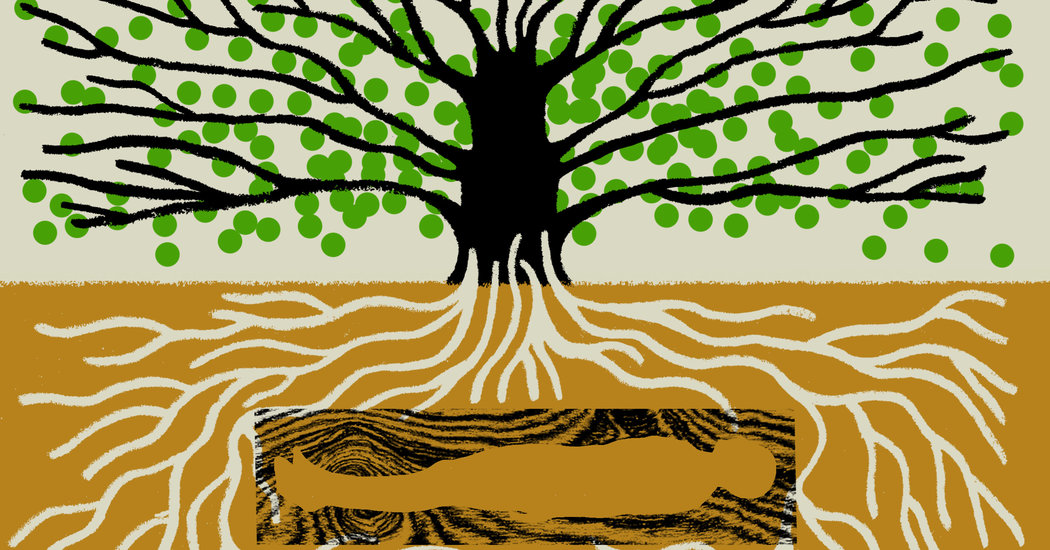

When I was in middle school, my dad built a prototype of his own coffin, and my mom kept her jewelry in the smooth pine box the size of her palm. This was a man who wore a suit and tie to work, but chopped wood from the backyard to heat our suburban house. He hiked the Appalachian Trail and Pacific Crest Trail with my mother, aiming to leave no trace in the wilderness, and he aspired to the same ideal in his death.

Two years after my mother died, my sister called with news I couldn’t comprehend.

My father, unbelievably, had also been hit by a driver while cycling to the farm. Wearing a bright reflective vest, he was biking on the shoulder of the road where he was killed, his neck broken, just like my mother. He’d started riding only on wide streets, rather than the narrow rural roads where Mom had died. But that didn’t save him.

His body was taken to the coroner’s office and then to the funeral home. While he wasn’t at home in his bed as he’d wished, the director agreed we could prepare his body for burial.

The time had come to use his plan.

Taking deep breaths in the foyer of the funeral home, my sister and I entered the refrigerated room, where he lay on a metal gurney, covered by a plastic sheet. I ran my fingers along the same pattern of wrinkles on his face that would soon mark my cheeks. He had only a few scratches on his body. We sang the gospel lullaby “All God’s Children Got Shoes,” and began to wrap him in the linens ironed by Mom’s hands.

Feeling the solid weight of his limbs against my chest, I lifted this compact, lithe man, with my sister holding his other side. We had his whole life in our hands as we placed his body into the wooden box, built the night before.

Our friend-turned-coffin-maker Jeff put our father into the back of his pickup truck and delivered him to the church where we kept an all-night vigil until the next day. My oldest daughter remembers standing at the cemetery with a shovel taller than her head while my dad’s band played “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Fifteen years later, I looked out at an Episcopal parish hall filled with 100 people in my home of Asheville, N.C. I wasn’t at a funeral. Instead, I was helping those gathered to anticipate their own deaths by sharing my parents’ story, as well as options for green burials that restore, rather than degrade the earth.

I had learned about a nearby conservation cemetery called Carolina Memorial Sanctuary that protected the land in perpetuity through easements and ecological restoration. And during this conference, I talked with death doulas who could advise my family about keeping my body at home before my burial. I’d made a will in my 30s, but the final wishes I’d written then didn’t seem to fit me anymore, in my early 50s.

Based on what I know now, I saw the possibility of changing my directives to use fewer fossil fuels, my last best act for my children.

That evening, I opened the file cabinet in my bedroom and took out the folder containing my will, cremation directive and advance care directive, which I hadn’t touched in more than a decade. I’d completely forgotten my instructions for a party after my funeral with beer and barbecue from Okie Dokies Smokehouse, a restaurant I once loved when my young children needed a quick fix of mac and cheese and ribs on a school night. (It claimed to offer “swine dining.”)

Since that time, my two daughters have grown from toddlers to teens, and my hair has turned a soft gray like my mother’s.

I started a handwritten list that included requests to keep my body at home, if possible, followed by a natural burial at the nearby conservation cemetery.

The director of the Center for End of Life Transitions, who spoke at the church that day, recommended placing these directives in the freezer, where they would be safe and easy to find. I’d picked up a refrigerator magnet and a zip-top bag for the documents labeled “Matters of Life and Death Inside.” I hoped to have years ahead to prepare my children for my absence. But after revisiting my wishes, I felt more prepared for what I couldn’t know, a legacy of love my father left me.

I told my 19-year-old daughter about my plans, including the option of keeping my body at the house until the funeral.

Her response: “Ew. Mom. No thanks.”

She explained, “If your body was in the house, I would feel like it was haunted. I couldn’t sleep.”

But of course, I am still here, baking banana bread from my mom’s recipes and singing my dad’s favorite songs. My plans are zipped up, ready for the time when I’ll have to fly away.

Mallory McDuff is a professor of environmental education and outdoor leadership at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, N.C., and is working on a memoir about love, loss and our changing climate.