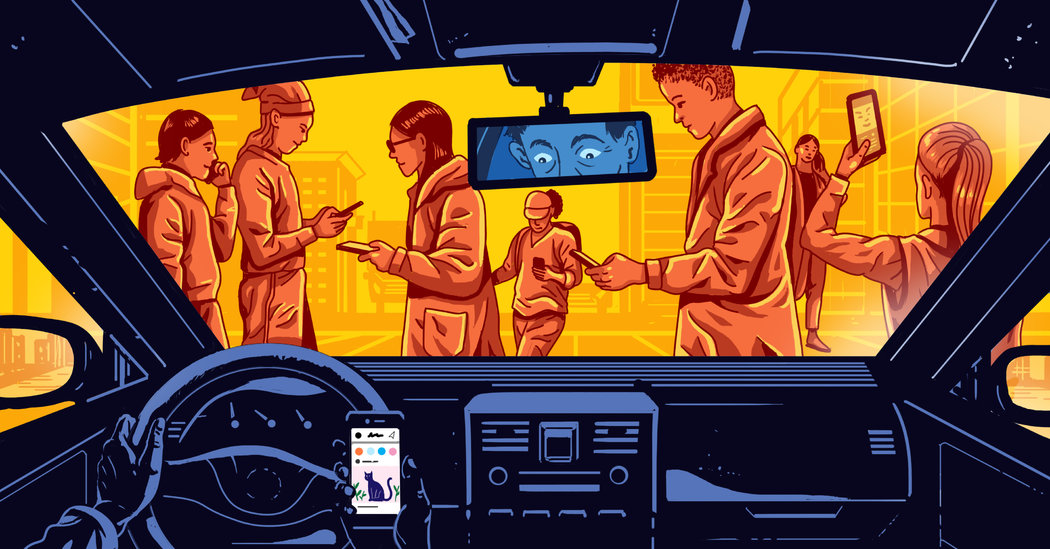

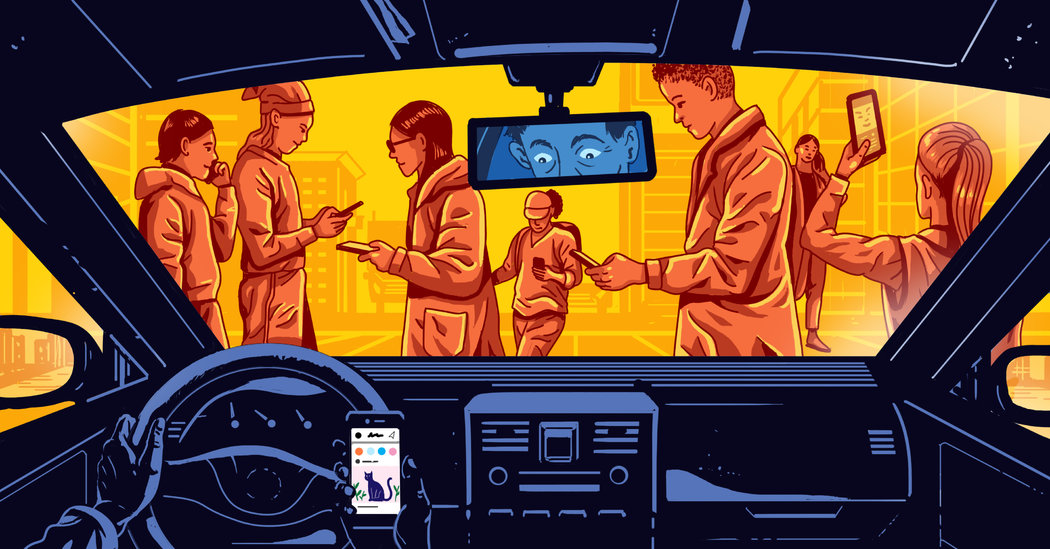

You’re walking around and a thought occurs: “I should check my phone.” The phone comes out of your pocket. You type a message. Then your eyes remain glued to the screen, even when you walk across the street.

We all do this kind of distracted walking, or “twalking.” (Yes, this term is really a thing.)

The behavior has spawned debates among lawmakers about whether walking and texting should be illegal. Some cities, such as Honolulu and Rexburg, Idaho, have gone beyond talk and banned distracted walking altogether.

But we shouldn’t let that reassure us. Last year, pedestrian deaths in the United States were at their highest point since 1990, with distracted drivers and bigger vehicles the chief culprits. So being fixated on a screen while walking can’t be safe.

“We know research-wise it’s not a good idea, and common-sense-wise it can’t be a good idea,” said Ken Kolosh, a manager of statistics at the National Safety Council, a nonprofit that focuses on eliminating preventable deaths. “We don’t ever want to blame the victim, but there’s personal responsibility all of us have.”

So why do we do it? I talked to neuroscientists and psychologists about our conduct. All agreed that texting while walking might be a form of addictive behavior.

But this column isn’t about pointing fingers. Rather, now is a good time to reflect on why we are so glued to our phones, what we know about the risks and how we can take control of our personal technology rather than let it control us.

Why We Text and Walk

People are, by nature, information-seeking creatures. When we regularly check our phones, we are snacking on information from devices that offer an all-you-can-eat buffet of information.

Our information-foraging tendencies evolved from the behavior of animals foraging for food for survival, said Dr. Adam Gazzaley, a neuroscientist and co-author of the book “The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World.” Studies have shown that our brains feel rewarded when we receive information, which drives us to seek more. That’s similar to how our appetites feel sated after we eat.

In some ways, smartphones were designed to be irresistible to information-seeking creatures. Dr. Gazzaley drew this analogy: An animal will probably stay in a tree to gather all of its nuts before moving on to the next one. That’s because the animal is weighing the cost of getting to the next tree against the diminishing benefit of staying. With humans and smartphones, there is no cost to switching between email, text messages and apps like Facebook.

“The next tree is right there: It’s a link to the next webpage, a shift to the next tab,” he said. “We transfer so easily that we don’t have to use up the nuts to move on to the next one.”

So we get stuck in cycles. At what point is this considered addiction?

Not all constant phone use was considered addictive, said Steven Sussman, a professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California. External pressures, like a demanding job, could force people to frequently check their phones. But when people check their devices just to enhance their mood, this could be a sign of a developing problem.

Another signal of addictive behavior is becoming preoccupied with smartphone use when you should be doing something else. An even clearer indicator is what happens when the phone is taken away.

“Let’s say you go out to the mountains and you don’t get reception, so you can’t use a smartphone,” Dr. Sussman said. “Do you feel a sense of relief? Or do you feel, wow, I want to get out of these mountains — I want to use the smartphone. If you feel the latter, that’s toward the addictive direction.”

Jim Steyer, the chief executive of Common Sense Media, a nonprofit that evaluates tech products and media for families, said there needed to be a broad public awareness campaign over the dangers of walking and texting in parallel with distracted driving.

“You have distracted pedestrians and distracted drivers, so it’s the double whammy,” he said. “Tech addiction hits in both ways.”

The Debate Over the Danger

Just how dangerous is distracted walking? The answer is: It’s still unclear.

Distracted walking is a relatively new area of research. There have been few studies to show the consequences of what the behavior can lead to. And some of the studies conflict with one another.

This year, New York City’s Transportation Department published one study, including data collected about pedestrian-related incidents in New York and nationwide, which found little concrete evidence to link distracted walking with pedestrian fatalities or injuries.

Yet the National Safety Council said the national data cited in the New York study did not include information on whether pedestrians were engaged in other tasks at the time of the incidents.

The council instead published a study conducted by the University of Maryland in 2013. It found that between 2000 and 2011, there were hundreds of emergency room visits related to phone use while walking, and the primary cause of injury was a fall.

While more research needs to be done on distracted walking, it’s indisputable that walking while texting is less safe than paying attention to your surroundings.

“When you’re busy doing secondary tasks like texting, you don’t judge gap distances in traffic as well, you walk slower, you make poor decisions, and you’re not aware of your surroundings,” said Mr. Kolosh of the National Safety Council.

How to Take Control

Obviously, the answer to not getting into dangerous situations by walking and texting is not to walk and text at the same time.

But that’s easier said than done, since people have trouble reining in their tech use. So several experts recommended exercises in self-control.

Melanie Greenberg, a clinical psychologist and the author of “The Stress-Proof Brain,” said people could practice being more mindful by asking themselves any of these questions:

-

Is this the most important thing for me to be doing right now?

-

Am I controlling my destiny, or am I letting tech control it?

-

How is my posture? Am I stressing my body out?

-

Am I going to cause myself harm?

Reducing access to the device can also be helpful, Dr. Gazzaley said. You could carry your phone in your bag instead of your pocket, making it more troublesome to pull out, for example.

The National Safety Council said that when pedestrians have to check their phones, they should stop walking and stand in a safe place. It also advised people wearing earphones to listen at a low volume.

Chris Marcellino, a former Apple engineer who led the development of the original iPhone’s notifications, recommended going into the phone’s settings and switching off notifications for all apps except those that are most important to you, like work-related apps.

“These are things that aren’t pertinent to your life that are bombarding you all the time,” he said.

Other tools, like the “do not disturb” function on both iPhones and Android phones, can be set to shush notifications temporarily.

Even knowing all of this, I caught myself the other day checking Twitter while crossing a parking lot. I reflected on this and realized Twitter was a waste of time.

So I deleted the app. Then I installed another one to block the Twitter website from my phone — just for good measure.