Legend has it that when Aesop, a slave, was brought to the Greek island of Samos, he so charmed the locals with his fables that they not only freed him, but honored him with a shrine.

That Aesop should have come to this Northern Aegean island for freedom holds a special poignancy today, even if it is only myth, because Samos is now home to one of the largest refugee camps in Greece. More than 4,400 asylum seekers from the Middle East and Africa live in and around an overcrowded camp above the port town of Vathy, the capital of Samos, waiting for clearance to cross the sea to the mainland and beyond, where they hope to find a future.

Unlike the other Greek island camps, which tend to be built in remote places, the Samos camp is close enough to town to allow refugees to walk to shops and the seafront, so when I was there in October and this summer, I was able to meet some and do what I could to help, even as I was also exploring the island, renowned for its dramatic mountains and dazzling azure seas.

Like the rest of Greece, Samos suffered from the economic crash of 2008, followed by a dip in tourism and a wave of refugees in 2015, so local business owners, volunteer organizations and refugees alike welcome tourists who wish to help and enjoy themselves at the same time.

Choosing an Airbnb in Kedros, a hamlet across the bay from Vathy, I spent my first evening sitting on a flagstone terrace, gazing across the water at the town and the Turkish mountains beyond, watching the Aegean blues shift and shimmer.

Renting an Airbnb or a room in a Greek-owned hotel helps the economy, and mine was an elegant stone house, with a swimming pool and a beach down the hill.

Coffee Lab is a cafe whose owners made breakfast every morning for refugees when the first big wave arrived in 2015.CreditAndrea Wyner for The New York Times

Ten minutes away by car, I discovered Lemonakia, a beach set in a sheltered cove. Most of the beaches in Samos are made of pebbles as smooth and round as marble eggs. This is no problem if you bring water shoes, and the stones keep the sea as clear as bathwater.

On my second day, I drove into Vathy to deliver a bag of children’s clothes to Samos Volunteers, the main nongovernmental organization on the island helping refugees. The organization is multinational, so its staff, many of whom are students, come from a wide variety of countries, including Romania, Spain, Britain and the United States. They were delighted to take my contribution, which I had known to bring from consulting their online list of urgent needs.

Giulia Cicoli, the education coordinator, suggested that visitors can choose what to bring from the list and either purchase the items at home or, even better, buy them from merchants in Vathy, thereby supporting the local economy and the refugees. It is easy, for instance, to buy much needed pens and pencils in a local stationary store and bring them to the nearby youth center, Mazi, run by an NGO called Still I Rise.

“We’re happy to have people walk in and give us their donations,” Giulia said. “And if you have a special skill, like knitting, yoga, writing or cooking, and would like to offer a class or two, let us know.”

Even better, a visitor can volunteer ahead of time to spend a month or more teaching, working with children, or simply sorting donations.

Samos Volunteers is run out of a building called Alpha Center down the road from the camp, and on any given day, the center is filled with asylum seekers chatting, sipping tea, or volunteering themselves. I met Ayad, a soft-spoken 23-year-old Syrian, this way. We fell to talking and agreed to meet the next day at a cafe called Coffee Lab. (Ayad asked not to be identified by his last name for fear of jeopardizing his asylum case.)

Some local cafes and restaurants refuse to serve refugees unless they are accompanied by someone who is clearly Western, but there are exceptions, and Coffee Lab is one. Its owners made breakfast for refugees when the first big wave arrived in 2015, and still welcome those who wish to sit inside or on the terrace. Another exception is Péra Vrékhi, an excellent restaurant owned by Manilos Patinilotis. After all, many Greeks understand what it is to be an exile, war and poverty having repeatedly scattered them all over the world.

Samians have their own particular history as refugees, as well, going back to 365 B.C., when Athenians captured Samos, exiled its inhabitants and seized their lands. According to Aristotle, their plight so affected the Spartans — the famously fierce warriors of the Trojan War — that they fasted for a day and donated the saved money to the refugees.

Hera, queen of the gods, who was supposedly born in Samos, was also a symbol of asylum. Her 8th century B.C. temple, the Heraion, the ruins of which are near the town of Pythagoria, was partly built as a sanctuary for refugees. Statues from the site are now in the Archeological Museum in Vathy, below the camp.

Today’s refugees are receiving less sympathy than did their predecessors, unfortunately, partly because Greeks are still hurting economically and don’t believe they can afford to support the continuing surge of refugees, and partly because the recent closings of European borders, the U.S. travel ban against some Muslim-majority countries, including Syria, and overcrowded camps on the mainland, have left more asylum seekers than ever trapped on the islands.

The Vathy camp, for instance, which sits on a former army barracks designed to hold 700 people, has swelled by more than 1,000 since June, according to the UNHCR. Shipping containers and tents are crammed into every corner, while families sleep in the open on the surrounding hillsides in tents they must buy or make themselves, plagued by bedbugs and rats.

Thus, when Ayad arrived to meet me at Coffee Lab with his friend, Hasan Majnan, 25, who is also Syrian, they were eager to talk and change the routine of their difficult days. We met several times a week to talk at cafes or to walk by the sea.

Ayad is tall, with wavy black hair and huge, expressive eyes. He and his family fled their town of Sabinah, just south of Damascus, in 2012, when it became impossible to go out for food without being shot at by military snipers, and after his uncle and his two young cousins were killed.

Hasan has a pointed, worried face and a shock of gray hair; a result, he told me, of the traumas he has endured, including the murder of his twin brother and his own torture by ISIS.

Their stories are tragic, but, as Ayad said, “Every story here is sad. Each is only a drop in the ocean.” He and Hasan find comfort in helping their fellow refugees, in their friendships, and in exploring the island.

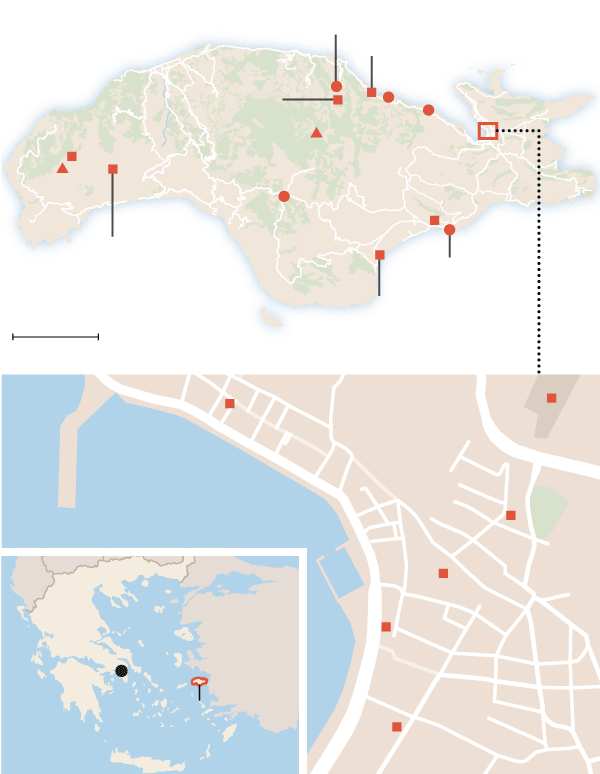

Between my days meeting with them and other refugees, I, too, explored. Samos is a diamond-shaped island less than a mile from Turkey, ringed by beaches and dominated by two major mountains, both of which offer spectacular hikes. June and early fall are ideal times to visit, when the water is warm and the air cool.

In the center of the island sits Mount Karvounis, lush with pine, olive, lotus and fig trees. My favorite hike was from the seaside resort of Kokkari up to the village of Vourliotes, a honeycomb of traditional stone houses clinging to the mountainside, their terra-cotta roofs decorated with pottery pigeons.

From there, I took a detour to Vronda Monastery, built in 1556 and the oldest in Samos. An imposing stone structure, it is inhabited by only three Orthodox monks. As I climbed, inhaling air scented with resin and thyme, I was rewarded with stunning views of vineyards ribboning the island, olive groves undulating from green to silver in the wind, and the glimmering blues of the sea.

The west side of Samos is wilder and largely protected as a park. Mount Kerkis rises in a dramatic heap of gray rock filled with caves, many of which were once inhabited by hermits. In one of these, the philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras, born in Samos in 570 B.C., is said to have hidden from the tyrant Polyckrates. To reach the cave, you have to climb a marked trail and then haul yourself up by a rope. If that’s too much, you can mount the nearby 320 white steps instead to the 11th-century chapel Panaghia Sarantaskaliotissa, nestled in the mouth of a different cave and decorated with faded frescoes of the same period.

A hike on Kerkis took me to another cave chapel, Panaghia Makrini, once used as a hermitage and thought to have been built in the 9th century. Inside, 12th-century frescoes of saints, jackals, birds and goats are still visible. Like most of the miniature country chapels of Greece, it is painted dazzling white.

The south side of the island is where to find sandy beaches, dramatic coastline walks, and most of Samos’s ancient history, including a 6th century B.C. underground aqueduct built by the engineer Eupalinos, who ingeniously designed the tunnel, which is nearly two-thirds of a mile long, to be simultaneously dug from opposite ends to meet in the middle — and so it does.

On my drives across the island, I often passed roadside “bee houses” selling honey. Costas Skallari, a native Samian, runs one of these, The Farm Store, a wooden hut on the south side of Mount Kerkis, near the town of Pirgos, where he was born. As well as honey, he sells the herbs that he collects early every morning, including “mountain tea” made of a wild leaf that is said to cure virtually every ill.

“What I love about Samos,” Costas said, “is that it is quiet and full of nature. People say the refugees have driven away tourists, but I don’t think so. It is a beautiful island for everyone.”

Between my explorations, I continued to drop by Alpha Center. More refugees were arriving every day, and the camp had grown so overcrowded that people had to wait in line for hours to get a meal, only to find that the food had often run out. When I returned in October, many volunteers were concerned that people would soon be starving, and freezing to death in their tents during the winter.

The day before I left, Ayad, Hasan and I talked about the overcrowding and the increased police harassment. “I understand this is their country, and they don’t want us here,” Ayad said. “We all wish we could go home. But we can’t.”

“We only want to be treated as human beings,” Hasan added. “Please, tell the world this.”

Helen Benedict teaches journalism at Columbia University. Her most recent book is the novel, Wolf Season.

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.