Last year, we had some leftover airline credit on Norwegian Airlines. On the day it was set to expire, in a panic, I asked my 4-year-old son, Holt, where we should go.

“I love pasta!” he said. “But not with red sauce.”

In retrospect, perhaps I should not have organized an entire trip around trying to prove to my 4-year-old that he did, in fact, like pasta al pomodoro; he just didn’t know it yet. Yet how could I ignore that ancient proverb of Italy, chiseled above the gateway to every town: Sucus ruber omnibus dilectus, “All love red sauce.”

Yes, Italy! We would go to Italy. At the time it seemed like such a good idea. Culture! Sun! Vespas! Ciao! It was only after buying the tickets that I remembered the problem with traveling with young children is that when it comes time to travel, you actually have to bring your young children with you.

So, what do you do? Namely, do you ruin your life on their behalf? With kids in tow you cannot have long, lingering 20-course dinners. (You cannot have two-course dinners.) You cannot spend a whole day in an art museum scrutinizing the pathos of Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro. You cannot while away an afternoon reading Dante’s “Inferno,” downing six bottles of Chianti as Pavarotti belts his way through Tosca.

In order for you to be happy, your children must be happy. If I’ve learned anything about living and traveling with children, it’s to keep things simple. Boil life down to its essence. Path of least resistance.

So, here was our entire agenda for our Italy trip in June: “Eat as much pasta as possible.” Full stop. Anything else that happened would be purely a bonus.

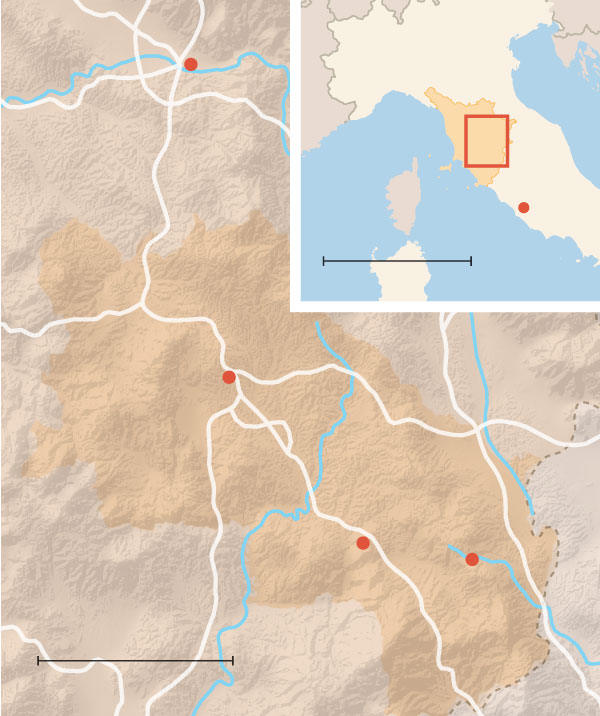

Our rough itinerary was to rent a car at the Rome-Fiumicino Leonardo da Vinci Airport and head up to Tuscany, spending three nights in the stunning Val d’Orcia region, where we would bounce around hilltop towns sampling the local pasta specialties. We would then flee north, to Siena and Florence. We would probably not see much art, if any. Our history lessons would be limited. We would eat pasta and then more pasta. We would turn pasta into a daily ritual, a prayer, a philosophical question, a prison sentence. We were either geniuses or fools. (Or both.)

Somehow we managed to survive the eight-and-half-hour flight to Rome trapped in a metal tube with our children and 200 other passengers.

The airport was complete chaos. We finally located our lost luggage and a car with four wheels and, after a two-hour drive, jet lagged and completely discombobulated, we pulled into the dream that is Chiarentana, a huge, ancient Tuscan farmhouse built around a cobblestone courtyard with a linden tree at its center. Chiarentana is on the sprawling La Foce estate overlooking a pastel valley of lavender and cypress trees. Olive orchards spill forth. Crickets buzz. The view from every window feels borderline illegal. Beauty has a way of simultaneously welcoming you and keeping you at arm’s length.

Iris Origo, an Anglo-American transplant, purchased La Foce in 1924 and proceeded to transform what was then a collection of poverty-stricken farms into a vibrant place, constructing an astonishing formal garden at the main La Foce residence, and building a school for the farm children of the valley. During World War II she took in several dozen orphans, which she wrote about in the evocative and slender “War in Val d’Orcia, An Italian War Diary 1943-1944.”

Outdoor dining at Trattoria Osenna in the village of San Quirico.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

Chiarentana is now run by Iris’s lovely daughter, Donata. They sell several varieties of their own olive oil, including the frantoiano, which can transform a simple piece of bread into a gustative epiphany of earth and arbor and sky.

The place bleeds history. But my son Holt did not care about any of that. He was intent upon setting up a cheap plastic bowling set in that magical cobblestone courtyard. He created an elaborate game with arcane rules that could only be played in this courtyard, under this linden tree. I tried playing with him, but got it all wrong.

“No, that’s the home pin,” he said, weary at such ignorance.

There is something refreshing about watching the very young play in a very old place. We must care about history, but we must not care too much. The wheel of time spins.

On our first full day in Tuscany we headed to the restaurant Dopolavoro La Foce, just down the road.

“Are you ready?” I asked Holt.

We ordered three pastas, including eliche with fresh ricotta and wild fennel. Eliche means propeller in Italian; the pasta is shaped like a spiral, or the path a propeller would make in the water. Holt enjoyed this information. Like many boys his age, Holt is fascinated by systems, shapes, how things work and don’t work; it seemed like his entire third year was composed simply of reciting a taxonomy of construction vehicles.

Exhibit A: Eliche and propeller paths

The pastas came. They were divine. Life shrunk to its simplest ingredients. We do not need much to be happy in this world: something to slurp, something to sip. Everyone sat very quietly eating, even Max, our youngest. We marveled at the path propellers make from our mouths to our stomach. Suddenly Holt held his fork aloft, eliche skewered on its tongs. “This is the best thing in my life!” he exclaimed.

From that very successful first lunch things became a bit wobbly. My children, like most children, do not sit at tables for extended periods of time. Why sit at a table? Tables are boring, flat things that cannot be slapped, climbed upon, taken apart without reprimand. Children wonder: Why do adults always sit at tables for hours and hours, talking and not talking?

My children preferred hanging out with Bertoldo, the depressive, wise donkey of Chiarentana who bleats at the sadness of mortality each morning. Holt loves a good patch of sand from which he can narrate the history of the universe. Max loves a good door threshold. Or a ramp. He will spend half an hour opening and shutting a door or running up and down a ramp. But neither of them will t sit at a table for very long. Oh no.

Children light candles in the Duomo of Siena.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

On our second day, Holt also made the declaration that he hated all old buildings. This did not bode well for our trip. He made this announcement after we visited the geometric Horti Leonini Garden in the village of San Quirico d’Orcia and came across a medieval tower that had been destroyed by the Nazis as they retreated from the countryside during World War II. In Holt’s mind, all old structures would fall down on top of us. Entropy was inevitable. He woke up in the middle of the night completely inconsolable.

Exhibit B: The Horti Leonini Garden

“I hate old buildings!” he wailed over and over. “I want to go home!” In the gloaming, Bertoldo, the donkey, commiserated.

We did not follow the logic of the toddler. We did not go home. We ate more pasta. So much pasta. In San Quirico, village of the fallen tower, we savored homemade pici al cinghiale at Trattoria Osenna. This is pasta made from a sumptuous ragu of wild boar. It will change your life.

Pici is the local style of eggless peasant pasta; it is like plump, irregular strands of spaghetti, stretched out by hand. The term pici comes from the Italian word “appiciare” which is the ancient action of rolling and coaxing out those long, lumpy strings. The owner of Osenna, Luca, told us his mother, the chef, could stretch a single strand of pici to over six feet long.

“You could wrap it around your whole body!” said Holt. Luca said this was not traditional but he would convey the idea to his mother.

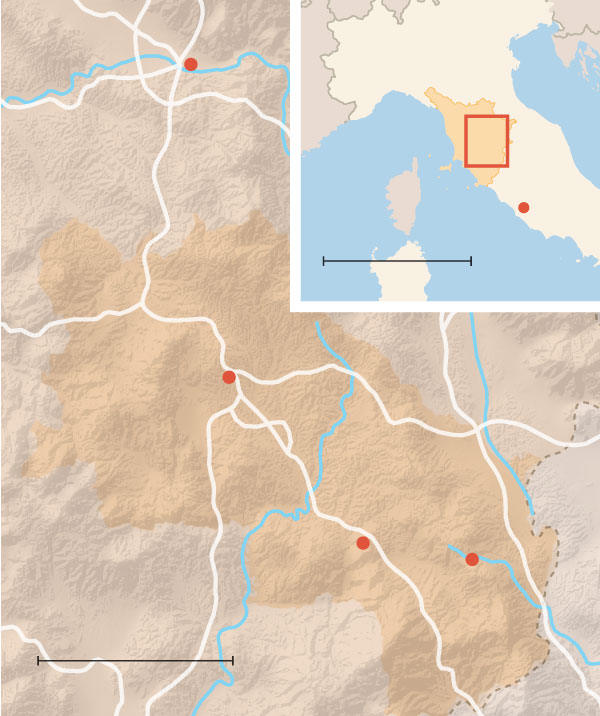

Exhibit C: The rolling of the pici Alla Vecchia Bettola is a Florentine restaurant with communal tables and iron pots hanging from the ceiling.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

After several days of drifting through the villages of the Val d’Orcia, a life I could easily adjust to, we headed north to one of the true gems of Italy, Siena, an ancient walled city of winding passageways and bountiful gelaterias that is a perfect size for kids and adults alike. We walked up the hill and suddenly found ourselves face to face with the Duomo, that jaw-dropping cathedral adorned in its distinctive black and white stripes.

I winced, wary of Holt’s allergy to antiquity, but he was awed by the intricacy of its facade, replete with biblical scenes, grumpy lions and saints frozen in various karate poses. Inside, we marveled at the giant mosaic covering the entire church floor and the Piccolomini Library, filled with an array of huge, illuminated manuscripts that took the breath away. On our way our of the cathedral, Holt wanted to light a candle.

“Everyday you come here to bless God,” he said, completely out of the blue. Then: “This is my favorite building in the world.”

The city is famous for its Palio di Siena, a 400-year-old manic horse race that circles the Piazza del Campio. Twice each summer 10 horses and riders representing the various “contrade” or districts of the city run pell mell around a temporary clay track.

The formal garden at the main La Foce residence in the Val D’ Orcia region of Tuscany. CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

We were in Siena a week before the first Palio of the summer, and the clay had just been laid, and rickety bleachers erected all around the racetrack. Imagining the screaming hordes, we sneaked through the ropes into the middle of the piazza, the still-wet clay sticking to our stroller’s wheels. We were practically the only ones in the whole square, a moment of perfect serenity. Holt pretended he was a horse. Max pretended he was Holt.

Later, after eating a divine tagliatelle al pesto made from zucchini and almonds and a simple, flawless spaghetti al pomodoro e basilico (Red Sauce!) which Holt declared was “pretty O.K.,” we wandered through the green oasis of L’Orto de’Pecci, once the site of a psychiatric hospital and now a cooperative garden with a little restaurant, resident peacocks and a sculpture of a giant steel head that you could walk inside called “Open Mind” by Justin Peyser. Everyone was happy: This was art that you could slap.

We probably should have just stayed in Siena. It is like that other ancient Italian proverb: Libentissime cum liberis uno loco se continere. “When your kids are content, don’t move an inch.” But my wife had never been to Florence and so we headed up the winding autostradale for the last leg of our trip.

Museo Leonardo Da Vinci in Florence is where children can crank and pull at his inventions.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

Our Airbnb was in Oltrarno, the hip, Brooklyn-like Florentine neighborhood just south of the River Arno, filled with little eateries and shops selling artisanal rucksacks and handmade puppets.

Our first day we ventured into the sweaty scrum of central Florence and were quickly repelled by a tsunami of tourists. Florence in the high season is a nightmare. You cannot breathe, you cannot move. Our whole family grew quite cranky until we bought some gelato alla stracciatella. It has been proven by science that gelato is the cure for all ills, including gout, gunshot wounds and existential despair.

We didn’t even try to make it to the Uffizi Gallery or see the famous sites. My traveler alarm bells kept going off: We were missing out on the Caravaggios! But you are always missing out with kids. That is kind of the point. The beauty is in the miss.

Instead, we headed to the small Museo Leonardo da Vinci, where the kids could crank and pull at all of his inventions, including what looked like the world’s first bow flex exercise machine. They were very happy. In one corner stood Leonardo’s helicopter, which resembled the eliche propellers we had eaten that first day.

Exhibit D: Leonardo’s failed helicopter Villa Il Castagno Wine Resort is near Siena.CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

“It didn’t work,” I said to Holt, pointing to the helicopter. “It couldn’t fly.” This felt perhaps more tragic to me than it should, a metaphor for our times. Good ideas that never take off.

“That’s O.K.,” said Holt. And it was.

To complete the famous Dead Scientist Museum Double, we visited the first-rate Museo Galileo (just past the foolish hordes waiting for hours to get into the Uffizi!) It’s a rich space filled with cosmographic spheres, a pantheon of cannon-size telescopes, sensuous maps of the heavens, and two of Galileo’s actual fingers.

One exhibit in particular caught my eye: a marble run with two paths of descent, the first a straight decline and the other a longer, lazy bend called the brachistochrone curve that goes down and then up again.

By all appearances, the straight line, the shortest path, is the quickest route to the bottom. Right?

Nope. Galileo discovered it was the brachistochrone curve, which, despite being longer, delivers the ball first. And as I watched Holt put marble after marble down each path, testing and retesting the hypothesis, I began to irresponsibly apply such principles to our little Italian adventure. The straightest way is not always the best way. Rather, by weathering the natural curves of life, by going down and then up, by lingering at the doorway for half an hour as Max joyfully closes and opens the door again and again, you are actually taking the more efficient path.

Boboli Gardens is a tiered Florentine paradise of ancient statues, geometric fountains and rambling hedgework. CreditSusan Wright for The New York Times

Our last evening in Italy we skipped into the Boboli Gardens just before closing. The evening sunlight was loose and pillowy. We were almost completely alone; the masses toiled in the city beneath. The Boboli is a tiered Florentine paradise of ancient statues and geometric fountains and rambling hedgework. In one clearing we came across a strikingly modern sculpture: a clean, white marble oval entitled “Secret of the Sky,” by Ken Yasuda. The perfection of the form was startling against the wilds of the surrounding greenery.

“It’s like a gem turned sideways,” Holt said. “It’s the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.” When you are 4, there is no such thing as hyperbole.

Nearby, we found a magical little restaurant, Alla Vecchia Bettola, with communal tables and iron pots hanging from the ceiling. They managed to seat us despite being packed with Florentines. After 14 straight meals of pasta, this would be our last.

By this point, the four of us were used to things. We were like a well-oiled machine. As soon as we sat, we ordered the children’s meals. The kids tolerated the tableness of the table. Max did not demand his customary ramp exercises. We had our iPhone apps at the ready but did not need them. We all seemed to sense this little experiment was coming to an end. A group from Quebec at our table remarked how well behaved our children were.

“They are not like this normally,” I said. “They have been trained. Like seals.”

The restaurant hummed. Locals laughed and made intricate gestures with their fingertips that meant all was not lost.

I had one more bite of ravioli. And then I was done. I had finally overdosed on Italian food, something I did not think was scientifically possible.

“Down,” said Max, pointing at the ground.

And down we went. We had taken the wandering path and arrived at this moment, just in time.

Reif Larsen is the author of the novels “I Am Radar” and “The Selected Works of T. S. Spivet,” which was adapted into a feature film, “The Young and Prodigious T. S. Spivet.”

Follow NY Times Travel on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Get weekly updates from our Travel Dispatch newsletter, with tips on traveling smarter, destination coverage and photos from all over the world.