T Introduces: Jessi Reaves

Looking at art can be tiring business, and resting spots in museums tend to be rare, crowded and generally uninviting. But at last year’s Whitney Biennial, where visitors of course knew not to touch the art, they came to an awkward consensus regarding the work of Jessi Reaves: They sat on it. In their defense, the New York artist makes sculptures with reassuring references to everyday chairs, tables and lamps — though rather than broadcast their functionality, her pieces challenge us to question the very concept of furniture. One of the pieces on view, “Basket Chair With Brown Pillow,” resembles a head-on collision between the 19th-century German cabinetmaker Michael Thonet’s classic bentwood Chair No. 14 and the sort of metal butterfly one finds in college dorms. “I didn’t anticipate the sheer number of people and the damage they could do,” says Reaves. “But you can’t create a nuanced instruction for interaction — it can’t be, Sit gently. It’s either all on or all off.”

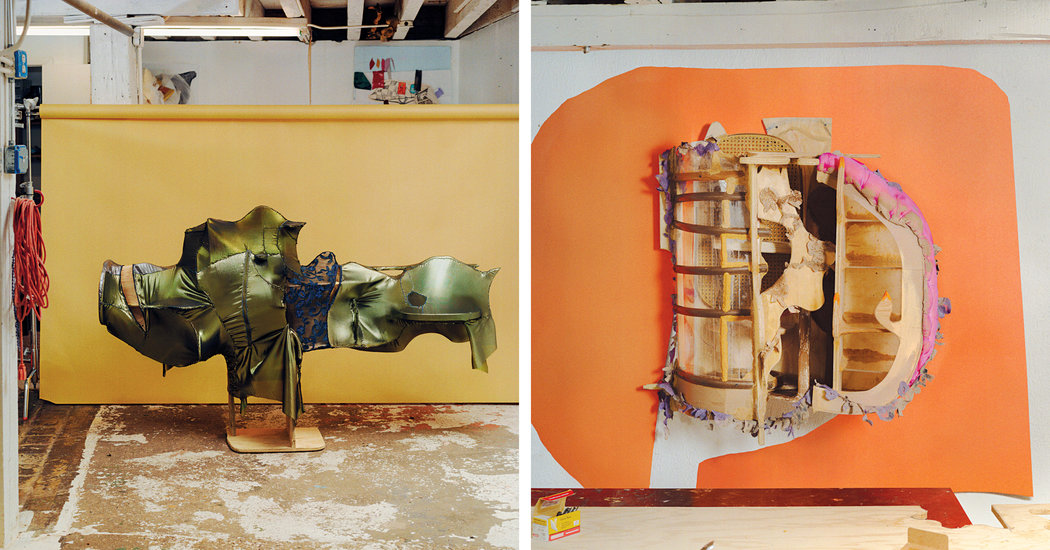

The 31-year-old Reaves, who studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, arrived at these more workaday forms when she started taking freelance jobs as an upholsterer after graduating. “It was amazing because I had all of these materials accumulating around me, and I liked the sensation of peeling things back and getting familiar with pieces in their unfinished state,” she says. She embarked on a series of chair sculptures, dressing a Thonet chair in a diaphanous pink slipcover so that it appeared to be wearing lingerie and covering a cheap plastic chair in jacket fleece in an approximation (or abomination) of an expensive Scandinavian model she’d seen at high-end furniture stores. “In design, there is a lot of theft of ideas, even as people aspire to make something new and iconic,” she says, adding, “which strikes me as really funny and bro-y.”

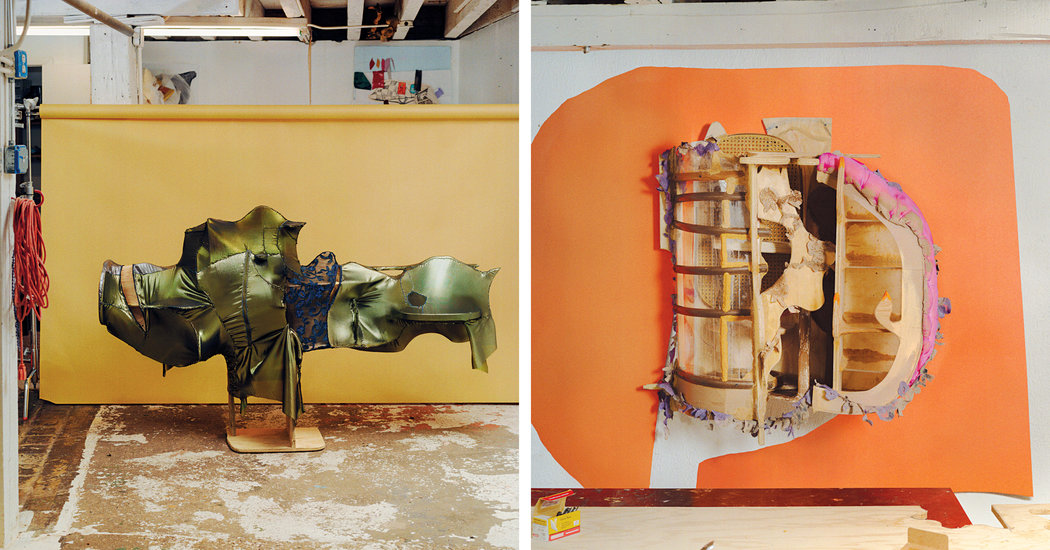

Reaves isn’t striving for the glory of invention but for nuanced riffs that play with ideas of both usefulness and beauty. Aesthetically, her pieces — erotically misshapen, with more than the edges left raw — have as much in common with the paintings of Jenny Saville than anything produced by Charles and Ray Eames. Earlier this year, she was selected for the Carnegie International, opening on Oct. 13 in Pittsburgh, where she’ll show curvaceous multimedia “recliners,” as well as a baroque chaos of plywood, caning and even a purse that, for lack of a better word, could be described as a shelf. There, her work will literally occupy the no man’s land between art and design, in a space bridging Carnegie Museum’s Hall of Architecture and its main galleries that was originally constructed to house the last office of Frank Lloyd Wright.

But while her body of work is sweepingly subversive, Reaves remains fascinated by the materiality and perceived purpose behind each piece. On the day I visit her studio, in the basement of a former carriage house in Chelsea, she shows me a large electric fan that she’s working on for her friends Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta, fashion designers whose own Whitney installation is now on display. “I love the fan because, unlike a chair, you don’t have to use it to activate it. It just acts on you,” she says. Still, she’s built a decorative wire cage and placed it atop a pedestal of scrap wicker, giving it, in effect, a special chair of its own. — ALIX BROWNE