One of the things we have lost in the digital era — and we have lost a lot — is a tributary medium of sorts, the tangible practice of holding an image in our hands that maps an emotional bayou of truth. Still photographs capture the private determination and personal integrity of their subjects in a way that, upon revisiting, makes selfies and iPhone pictures feel fleeting, contrived and manufactured.

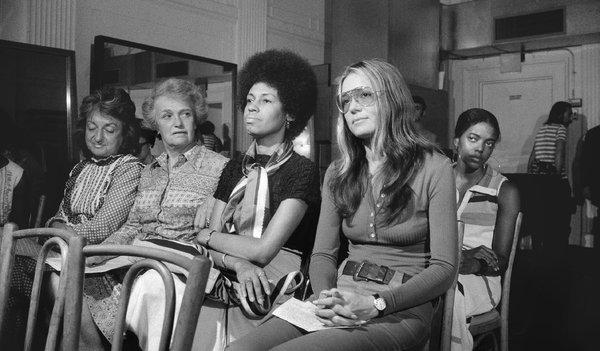

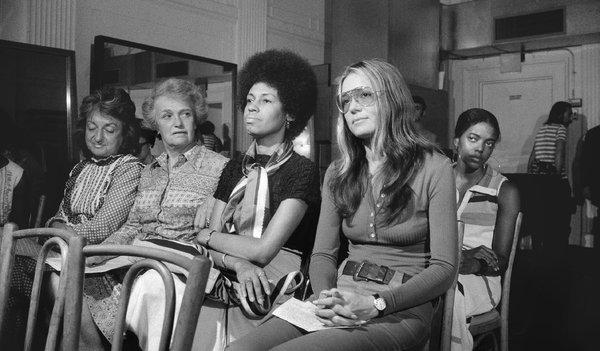

At an early meeting of the National Women’s Political Caucus, from left in the foreground: Betty Friedan, Elinor Guggenheimer, Ms. Norton and Ms. Steinem. July 19, 1971.CreditDon Hogan Charles/The New York Times

In perhaps my favorite image from The New York Times photo archive — an elegant profile — Eleanor Holmes Norton is kneeling on a stage, with Gloria Steinem standing at her feet. It was the 10th anniversary of the National Women’s Political Caucus, and Eleanor, a co-founder of the caucus, was set to deliver the keynote address. She’s dressed in white, with sling-back heels, and wears her hair in a short-cropped Afro. Her mouth is slightly ajar, because she is talking. Gloria’s mouth draws lip to lip, closed, because she is listening. She has always listened to black women. I know because it is evidenced in the photographs — which are templates of integrity — but also because she has always listened to me.

I have struggled with trust in my interactions with white women. This is among the topics I’m exploring in depth in my upcoming memoir, “Surviving the White Gaze.” So it is no small thing for me to say that Gloria Steinem, not so much the icon as the woman, is among the very few I trust resolutely, instinctively and without conflict or concern. And this was before I saw these archival photographs.

The Times’s archives are rich with pictures of Gloria. They weren’t edited to reflect a certain truth, and yet the truth of the images is evident. Photograph after photograph of Gloria show her with so many of the black women she worked with during the 1970s — Florynce Kennedy, Evelyn Cunningham, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Jane Galvin-Lewis, Shirley Chisholm, Fannie Lou Hamer — wherein we see the embodiment of intersectional feminism. In each photo, there is ease and intent, focus and fury and, perhaps above all, a nearly palpable, unprompted sense of racial solidarity that makes me wonder why it’s still so hard for us to get it right today.

I first reached out to Gloria in an email over a decade ago. I was working on a project about race, racism and white accountability — not the accountability of white women expressly, but of whiteness (before we were regularly using that term in common parlance), and its role in shaping perceptions of race and perpetuating black stereotypes. I wanted to talk with white public figures from a variety of fields, who were smart, honest and self-aware, and who had created culturally important work that also contributed somehow to the national conversation about race, but not in a glaringly obvious way. Gloria was at the top of my list — others included Tony Kushner, Cindy Sherman and Agnes Gund — because in my early 20s, I loved New York Magazine, and she was among the magazine’s first columnists.

Also, from reading about the genesis and early days of New York Magazine, I knew that she had written this very famous story in 1969, “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation,” in which she writes about black women and people as, well, human. And then, of course, that she founded Ms. Magazine with the black feminist and child-welfare advocate Dorothy Pitman Hughes. To be honest, I was actually a little skeptical of her intentions, as I was when I met my white husband 16 years ago, who was that day traveling to a conference on race at Harvard. (“Who is this white person who cares about race, who considers blackness and black culture, without expecting any accolades in return?” I remember wondering.)

Gloria responded to my email immediately. We talked for about an hour, and she asked me as many questions as I asked her. Later, in a follow-up email, she recommended a book she was reading that had reminded her of me, “Cultural Memory: Resistance, Faith and Identity” by Jeanette Rodriguez and Ted Fortier, a book that only someone who had truly heard and understood the complicated origin of my specific interest in race and racial identity would recommend.

In the years since our first meeting, I have turned repeatedly to Gloria as I navigated my nonlinear career in media. At one point, when I was working at an online company, there was a white woman high up with a lot of power, who was both racist and constantly trying to sabotage me. At my wits end, I emailed Gloria, who wrote back: “Don’t you dare let her take your confidence or peace of mind away for a millisecond!”

That’s the kind of forthright pledge to black women — to me, to us, to our peace of mind — I see in these remarkable images, some sepia-toned from weather and wear, others blurry or maybe rushed, but never dishonest. There is testimony in these photographs. A vivid telling of something unsaid. Of women gathering each other up. A promise of no one’s concern but their own. I learned that promise from Gloria.

Rebecca Carroll is a cultural critic, host and editor of special projects at WNYC, and a critic at large for the Los Angeles Times. She is also the author of several books about race and blackness in the United States, including “Sugar in the Raw.” She is currently at work on her memoir, “Surviving the White Gaze,” due out from Simon & Schuster in 2020.