He photographed Shirley MacLaine dancing with Rudolf Nureyev at a party in Malibu. He shot the actor Dennis Hopper and the singer Michelle Phillips during their eight-day marriage, including a joint-smoking moment in the bathtub (both were fully clothed). And he caught Princess Margaret all but swooning over Paul Newman as Alfred Hitchcock stared straight ahead.

The photographer Orlando Suero chronicled the lives of stars from 1962 to the mid-1980s, as the golden age of Hollywood dipped into its twilight. He took particular delight in capturing celebrities with each other, in their element or not. But he was perhaps best known for his portraits.

Among his more stunning photographs was one of an elegant Jacqueline Kennedy in a gown lighting candles at a formal dinner table in Georgetown in 1954. Mr. Suero called it his Iwo Jima photo — his career-defining shot.

Mr. Suero (pronounced SWEAR-oh) died on Aug. 19 at a nursing home in Los Angeles. He was 94.

His death was confirmed by his son Jim, who said he had survived a number of strokes.

Mr. Suero, a native New Yorker, started taking pictures at 14 with a used Kodak Jiffy camera given to him by his father. He was soon working at camera shops and photo labs, including a stint at Compo Photo Color in Times Square. There he printed images for “The Family of Man,” Edward Steichen’s monumental 1955 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

He printed those large images for the exhibition more than a year in advance. By the time it opened, he was already moving up in the photography world.

While at Compo, Mr. Suero had received a side assignment to photograph a children’s event sponsored by Hanover Bank. Max Lowenherz, who owned the Three Lions Picture Agency, saw Mr. Suero’s photos in the bank window, asked who the photographer was and hired him.

It was Mr. Suero’s first professional job as a photographer, his son said, and he was eager to make his mark. So he proposed taking a series of pictures of the young Senator John F. Kennedy and his new wife, Jacqueline. Mr. Lowenherz was not interested because so many others were writing about the couple. But he said that if Mr. Suero could find a publication willing to run his pictures, he would agree.

Mr. Suero pitched the idea to McCall’s magazine, which loved it. The young photographer ended up spending five days with the newlywed Kennedys at their modest red-brick home in Georgetown, on the carefree cusp of an extraordinary period in American history.

His photos showed Jackie kneeling in the living room, sorting her record albums; Jackie weeding the garden while Jack, in a T-shirt, read the newspaper; and, of course, several images of Jackie lighting the candles at her dinner table, one of them a frame so perfectly composed and luminous that it looks more like a painting than a photograph.

Mrs. Kennedy herself was impressed and sent Mr. Suero a note. “If I’d realized what a wonderful photographer you were, I never would have been the jittery subject I was,” she wrote. “They are the only pictures I’ve ever seen of me where I don’t look like something out of a horror movie.”

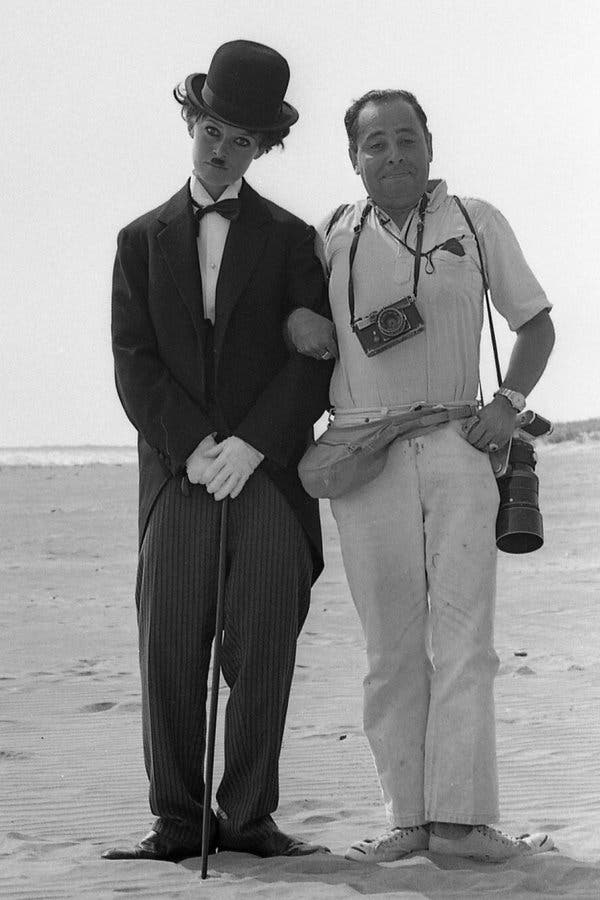

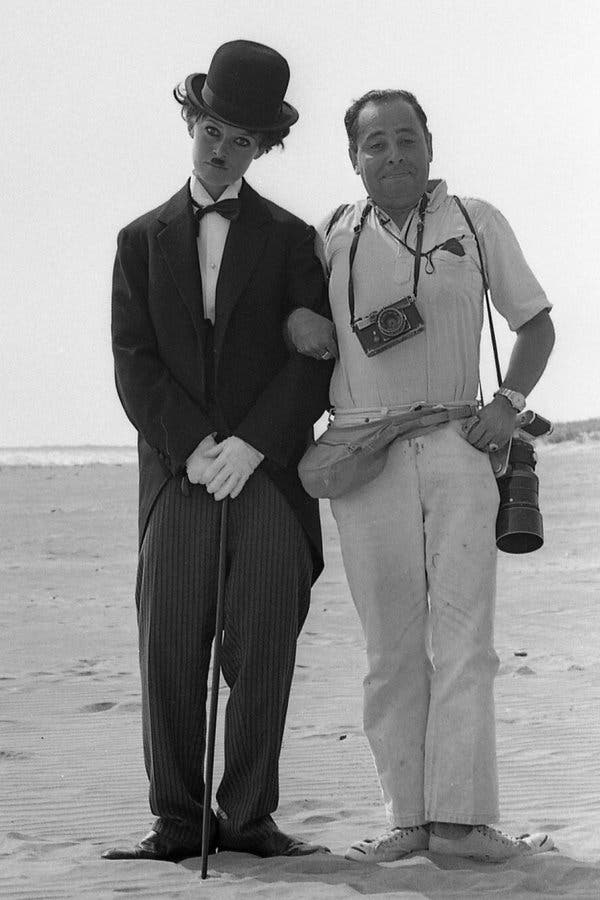

Mr. Suero later gravitated to Hollywood, where he went on to make a name for himself photographing the beautiful people. His favorite subjects included Natalie Wood, Michael Caine, Sharon Tate, Claudia Cardinale and Brigitte Bardot, whom he photographed lounging on a bed by the ocean and, later, dressed as Charlie Chaplin.

His lens also caught Jack Nicholson, Julie Andrews, Faye Dunaway, Robert Redford, Diana Ross and many more.

He served as a still photographer on movie sets, including those of “Torn Curtain” (1966), “Hell in the Pacific” (1968), “Play It Again, Sam” (1972), “Lady Sings the Blues” (1972), “Chinatown” (1974) and “The Towering Inferno” (1974).

Mr. Suero struck up a particular friendship with Lee Marvin, who, like Mr. Suero, had joined the Marines during World War II. When they became acquainted in Hollywood, they realized they had met before: at a military hospital in New Caledonia, during the war in the South Pacific. Jim Suero said Mr. Marvin was his father’s “one true friend from Hollywood.”

In the midst of all the glamour, Mr. Suero suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. He found comfort and joy in taking pictures, but when he wasn’t working he could sink into depression.

“When you come back, the war doesn’t end for you,” he wrote in “Orlando: Photography” (2018), a collection of his photographs.

“It stays with you for life for the most part,” he added. “Photography was my solace.”

Orlando Vincent Suero was born in Manhattan on May 30, 1925. His father, Vicente Andres Suero y Seoane, originally from Cuba, was a nightclub manager in Manhattan and Miami, and his mother, Ofelia (Dominguez Ayala) Suero, originally from Mexico, was a homemaker.

Orlando grew up in Washington Heights and attended P.S. 132. His first job was as a copy boy at The New York Times, where one day in 1943, at the age of 17, he got a surprising break.

He had been despairing at how clueless the older writers sounded in describing the red-hot trumpeter Harry James and his band, so the editors asked him to write his own story about a James concert at the Paramount.

“Jive, as a Hep-Cat Hears It,” read the headline, with the subheading, “17-Year-Old Beats Out a Panegyric to Its Glory,” conveying Mr. Suero’s frenetic style and liberal use of a vocabulary so baffling to the editors that they asked him to append a glossary of terms (“slush pump” = trombone; “coffins” = pianos; “coo for moo” = worked for his money).

Mr. Suero joined the Marines that year and headed to the South Pacific with the Sixth Marine Division. He was shot in the arm, received a Purple Heart and was discharged in 1945. He returned to New York and attended the New York Institute of Photography, now an online school.

He met his future wife, Margaret Ann Greenslade, after the war. They married in 1951. In addition to their son Jim, she survives him, as do their daughter, Wendy Breuklander; another son, Chris; four grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

Despite the success of his Kennedy photos, Mr. Suero found that work in New York was spotty, so he signed on with the John Deere Company in Moline, Ill., where he took industrial photographs for advertising from 1961-62.

“It was horribly depressing, and, coupled with my dad’s PTSD, it was a real rough time,” Jim Suero said. He stayed in Moline for about a year before the move to Hollywood, where celebrities found him unassuming and easy to work with.

Many of his photos were never published. His son Jim and a friend, the producer Rod Hamilton, discovered them in boxes a few years ago and compiled them into “Orlando: Photography,” which reviews said finally gave Mr. Suero his proper due at 93.

“My father is very humble about his work,” his son wrote in the book. “He is very shocked that his photos have come back to life because he never considered himself to be a great photographer. Frankly, he never thought of himself as worthy of a book. But he is embracing it, that’s for sure.”