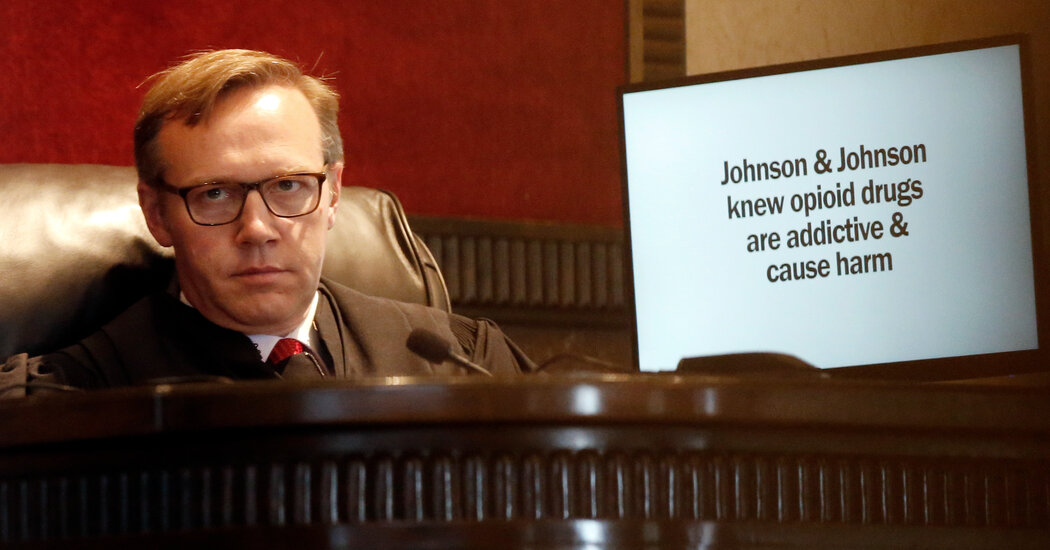

Oklahoma’s highest court on Tuesday threw out a 2019 ruling that required Johnson & Johnson to pay the state $465 million for its role in the opioid epidemic. It was the second time this month that a court has invalidated a key legal strategy used by plaintiffs in thousands of cases attempting to hold the pharmaceutical industry responsible for the crisis.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court, 5-1, rejected the state’s argument that the company violated “public nuisance” laws by aggressively overstating the benefits of its prescription opioid painkillers and downplaying the dangers.

The ruling, along with a similar opinion by a California state judge on Nov. 1, could be a harbinger that plaintiffs’ hopes for favorable resolution in courts nationwide against opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers will be dashed. The decision could also embolden the companies to dig in.

But because most public nuisance laws are state-specific, it is unclear how much impact the Oklahoma decision could ultimately have on cases elsewhere. The Oklahoma judges’ decision underscored their reading of their state’s law.

“Oklahoma public nuisance law does not extend to the manufacturing, marketing and selling of prescription opioids,” the judges wrote in Tuesday’s majority opinion.

According to federal data, abuse of opioids has contributed to the deaths of some 500,000 people in the United States since the late 1990s, and the toll has worsened during the Covid pandemic.

The Oklahoma case was the first state lawsuit against an opioids manufacturer to come to trial. The ruling, in August 2019, was a heartening signal to plaintiffs’ lawyers around the country that their legal strategy could prevail — even though the amount of the company was ordered to pay was considerably less than the $17 billion sought.

In a statement, Johnson & Johnson, referring to Janssen, its pharmaceutical division, said it had “deep sympathy” for everyone affected by the opioids epidemic. But the company added: “The clear and unassailable decision by the Oklahoma State Supreme Court reflects the facts of this case: Janssen’s actions relating to the marketing and promotion of these important prescription pain medications were appropriate and responsible and did not cause a public nuisance.”

In their opinion, the judges gave weight to the company’s response that it had not promoted its products in recent years and had sold off one of its product lines in 2015. The judges decided that manufacturers could not be held “perpetually liable” for their products.

The Oklahoma attorney general’s office had contended that health is a public right that Johnson & Johnson violated under the state’s public nuisance law. Other opioid manufacturers targeted in the state’s lawsuit, including Teva and Purdue Pharma, settled their cases before this bench trial against Johnson & Johnson began in May 2019. This decision does not affect those agreements.

John O’Connor, the Oklahoma attorney general, expressed disappointment with the decision, but said: “We are still pursuing our other pending claims against opioid distributors who have flooded our communities with these highly addictive drugs for decades. Oklahomans deserve nothing less.”

In the new ruling, the judges said that Oklahoma’s 1910 public nuisance law typically referred to an abrogation of a public right like access to roads or clean water or air. The judges found fault with the state’s case, saying it failed to identify a public right under the nuisance law and had instead attempted to apply a “novel theory” to what was more likely a products liability case.

The harm alleged by the state, the judges said, stemmed from the company’s legal product — prescription opioids approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Individuals suffered, the court decided, rather than the public at large.

Other case flaws cited by the judges echoed critiques made earlier this month by a California state trial judge who also found in favor of Johnson & Johnson. The company, the Oklahoma judges said, had no control over the distribution and use of its product once the drug left its purview — an argument used successfully by gun manufacturers to turn aside public nuisance litigation.

“Regulation of prescription opioids belongs to federal and state legislatures and their agencies,” the Oklahoma judges wrote. They were alluding to the F.D.A., as well as to the Drug Enforcement Administration, which is supposed to monitor pill diversion, and to the state’s own prescription monitoring program.

Elizabeth Burch, a law professor at the University of Georgia, cautioned that these two decisions should not be interpreted too broadly to predict the fate of other cases wending their way through courts, because other states have their own public nuisance laws.

She noted that the Oklahoma ruling went even further than the California decision, because it stated that public nuisance law couldn’t be used against any entity in the drug supply chain, including distributors and pharmacies.

But she said the ruling could potentially influence plaintiffs’ response to Johnson & Johnson’s major national settlement offer in July, when it proposed to pay $5 billion over nine years to resolve all opioid litigation against it.

The company’s offer has to be accepted by a majority of the thousands of local governments that have sued.

“If I was a plaintiff that was on the fence about whether to enter the J.&J. settlement, this ruling might push me closer to settling, if I was risk averse,” Ms. Burch said.